Comment: To patent or not to patent?

Issue: Microbial Tools

15 May 2018 article

An application for a patent is a deal between the inventor(s) and the country in which it is filed. In exchange for full disclosure, the inventors can protect their invention for up to 20 years. In theory, by revealing their invention publicly, others can benefit by using it as a springboard for further developments. Without a patent, inventors are almost powerless to stop someone else exploiting their invention.

When to apply for a patent… and when not to

There’s a common misconception that, to be granted a patent, you have to invent something ground-breaking, but this is not true. A useful question to ask is: have you discovered something which is beneficial enough for someone to want to copy it? This could be a simple product improvement, but nonetheless it may be patentable. A patent is granted for inventions which are useful, and new and inventive over everything else that has gone before. A patent is a ‘negative right’ in that it doesn’t enable you to start making or using an invention, but it does allow you to stop others from doing so. Therefore you should also consider if you will infringe someone else’s patent before exploiting your invention. The Espacenet website run by the European Patent Office (EPO) is a fantastic starting point to search for similar, previously filed patent applications which might have an impact on the assessment of novelty and inventiveness.

Once a patent is granted, renewal fees have to be paid to keep it in force, and to enforce your patent against infringers, you need the money to fund a potential court action. Therefore, you need to decide if you think you can make enough money from your invention to fund these or if your invention is attractive enough for businesses to invest in and/or license it.

How to apply for a patent

You can apply for a patent yourself, and the UKIPO has many resources to help you do this. However, this does involve risks that the patent may not be sufficiently robust and could be exploited by competitors. Patent attorneys train for many years to be able to draft good applications which not only maximise protection for inventions, but also minimise the risk of others circumventing the patent. They can also guide your application through to grant of the patent and help you file applications abroad. This comes at a cost, however, and for preparing and filing a UK application, a patent attorney will typically charge between £4,000 and £6,000.

An application comprising a description of and the claims covering the new inventon must be submitted. The description is similar to a scientific publication in that the background, methods and results are described. The claims are statements which set out the boundaries of the protection you want. It is possible to make applications in individual countries, collectively in Europe or to make an international application.

Dos and Don’ts

Do:

- Keep the invention confidential before filing an application.

- Research – not just Google, use Espacenet and, if you can afford it, request a professional patentability search.

- Get advice.

- File as early as possible – the earlier you file, the fewer prior publications can be cited against your application and the earlier protection can begin.

- Check your freedom-to-operate so you won’t infringe someone else’s patent rights.

Don’t:

- Publically disclose the invention.

- Talk to anyone about your invention pre-filing – if you absolutely have to, get a signed NDA first.

- Think that copyright will protect your invention.

Biotechnological inventions

In Europe and the UK, there are many rules on what can and can’t be patented in relation to biotechnological inventions. Pre-existing phenomena and creations of nature are non-patentable, but non-naturally occurring organisms constructed using biotechnology are patentable. For example, human cloning, modification of the human genome and commercial uses of human embryos are not patentable. However, human genes, stem cells, and micro-organisms themselves, such as bacteria, yeast, fungi, algae, protozoa and human, animal and plant cells can all be patented. Patents can also be obtained for products produced by micro-organisms, such as antibiotics or enzymes, and processes involving micro-organisms. Micro-organisms freely occurring in nature are not patentable as such, but they could be if isolated from their environment or produced by a technical process.

There are also unique considerations when filing biotech patent applications such as making a deposit of a micro-organism and filing sequence listings for nucleotides and amino acids.

Depositing micro-organisms

A patent relating to a micro-organism must provide enough information to put the invention into practice. If this is not possible in writing then a deposit of any disclosed micro-organisms should be made. Samples of micro-organisms can be deposited under the Budapest Treaty with an International Depository Authority (IDA).

Patent filings

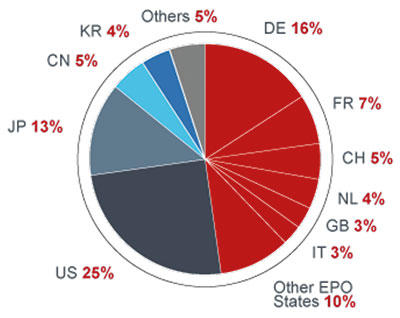

Origin of patent applications at the EPO in 2016. Source: EPO website |

|

In the UK, academics are often under pressure to publish their work in high-profile journals rather than file patent applications. Therefore, UK institutions may be losing out on potential revenue from patented inventions. In contrast, industrial research groups focus on building a strong patent portfolio rather than a publishing record. A publication can provide status and more grant funding, but it does not give you the legal right to stop someone gaining financially from your research.

Biotechnological patent applications represented about 4% of patent applications filed at the EPO in 2015, but this is a growing area. The top applicants in the biotech field in 2016 at the EPO included many universities and public research institutions, including the Institut national de la sante et de la recherché medicale (111 applications), Harvard College (37 applications) and the Technical University of Denmark (30 applications) (Source EPO website, Annual Report 2016). Disappointingly, despite their global reputations, no UK universities appeared among the top applicants.

As shown above, only 3% of total patent applications filed at the EPO in 2016 were from the UK.

As shown in the table below, the UK also lags behind in terms of US patent application filings. The table shows the number of patent applications per originating country filed at the USPTO and EPO in 2015.

Number of patent applications filed at the EPO and USPTO in 2015 per originating country. Source: EPO website.

|

Country of origin |

No. of European patent applications |

No. of US patent applications |

|

UK |

5,051 |

6,417 |

|

France |

10,760 |

6,565 |

|

Germany |

24,807 |

16,549 |

|

US |

42,597 |

140,969 |

|

China |

5,728 |

8,116 |

|

Japan |

21,421 |

52,409 |

Conclusion and the future

Even in a world where developments are seemingly occurring at a faster and faster rate, the importance of patent protection in attracting potential investors is still vital, and no other system exists which can provide fair protection for inventors whilst fuelling innovation by providing public disclosure of inventions.

The UK currently seems to lag behind the US, China and Germany in terms of filing patents, and it appears that UK universities are not maximising potential income opportunities through patenting their inventions. Awareness of patents needs to be raised so that opportunities to patent inventions and to generate income from them are not missed.

Number of patent applications filed at the EPO and USPTO in 2015 per originating country. Source: EPO website

Alice Smart

Trainee Patent Attorney, Manchester Office, Appleyard Lees IP LLP, The Lexicon, Mount Street, Manchester M2 5NT

[email protected]

Alice Smart has a BSc in Genetics and Biochemistry from Aberystwyth University, and a PhD in Pharmaceutics from UCL. Alice has also worked for Wyeth Research and Astra Zeneca. Since 2014, Alice has worked at Appleyard Lees, specialising in the filing and prosecution of biotechnological patent applications.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

Helping inventors obtain the protection they deserve for their inventions. I find it particularly satisfying when I can find strong arguments to overcome objections raised by patent offices.

How do you see this field changing in the future?

I believe patent applications for biotechnology-based inventions will continue to rise. Inventors will continue to push the boundaries in this field and challenge the law, and those who interpret it, on what can and should be patented.

Image: Claudio Ventrella/iStock