HIV worldwide in 2018

Issue: HIV and AIDS

06 November 2018 article

36.7 million people have HIV. The number is so large as to be incomprehensible, and the oft-used term ‘epidemic’ becomes almost reductionist. Behind the figures are the stories of individuals.

Imagine Tima, an 18-year-old Kenyan woman whose husband is admitted to hospital with tuberculosis and receives a new diagnosis of HIV. Tima is faced with the fear of raising their child alone. Imagine Bindiya, a 30-year-old ‘hijra’, an Indian transgender woman, who sells sex in a park near Mumbai railway station; she knows she has HIV but fears discrimination if she seeks treatment. Imagine Nikolai, the 24-year-old Russian man who injects heroin and does not know he is HIV positive; he does not access drug treatment services as he fears being branded an addict.

These vignettes, based on true accounts, remind us that HIV is a diverse disease which often affects the most vulnerable amongst us. This article describes the global fight against HIV and argues for the importance of remembering the rights of individuals such as Tima, Bindiya, and Nikolai.

Seismic changes

The last 10 years have brought seismic changes in the science behind HIV treatment and prevention. We now understand that ‘undetectable equals untransmissable’: a person with HIV who has an undetectable viral load does not transmit HIV to partners. We understand that starting treatment soon after diagnosis (or possibly immediately), regardless of their CD4 count, reduces morbidity and increases life expectancy. We understand that antiretrovirals can be used as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to greatly reduce the risk of acquiring HIV sexually. HIV drug treatments are available as single tablets, and modern combinations have fewer side effects and greater robustness against treatment failure than ever before.

Against this backdrop, the international community has adopted a series of ambitious goals that would previously have been unthinkable. In 2015, the United Nations adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals; the third of these sets the goal of ending HIV as a public health threat by 2030. This goal was reaffirmed in 2016, with the United Nations General Assembly Political Declaration on Ending AIDS, subtitled ‘on the fast track’, and promising to intensify efforts towards ending the AIDS epidemic. This seeks to reduce new HIV infections from 1.8 million in 2016, to fewer than 500,000 by 2020. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) also set a 90:90:90 target, which covers what is known as ‘the cascade’ of HIV care. By 2020, 90% of people with HIV will be aware of their status, 90% of these will be on treatment, and 90% of those on treatment will be virally suppressed. How well are we doing?

Prevention

In the early 2000s, HIV prevention was seen to be as ‘easy as ABC’: to avoid acquiring HIV, people simply had to abstain from sex, be faithful to one partner and use condoms. The complicated reality was that people at risk of HIV might not want or be able to adopt these behaviours, and policies based on an ABC approach overlooked the sexual and reproductive rights of the individual. The exemplar is now ‘combination prevention’. This approach combines biomedical interventions (including condoms, treatment, PrEP and voluntary medical male circumcision) and behavioural interventions (for example, sex education, infant feeding education), but also incorporates structural changes. Structural changes address underlying human rights issues, including decriminalisation of sex work, gay sex and individual drug use, and empowering women and girls.

In July 2018, UNAIDS warned of an emerging ‘prevention crisis’. It argues that the partial success of programmes to date has weakened the sense of urgency required to meet 2020 targets. Relatively few health systems can launch combination prevention packages at sufficient scale. Therefore, most progress is made in high-income cities, and districts in eastern and southern Africa that act as research hubs. It also warns of the ongoing detrimental effect of stigma and discrimination in HIV prevention efforts.

The first ‘90’: knowing your status

At the end of 2017, three quarters of people with HIV knew their HIV status. This represents vast progress in HIV diagnosis. In the early days of the epidemic, a positive result meant a terminal diagnosis, stigma and social exclusion, giving rise to a ‘voluntary counselling and testing’ model, in which a person actively attends a testing unit and receives counselling about the test. Since the publication of WHO/UNAIDS guidelines in 2007, there has been a huge paradigm shift and vast scale-up. HIV tests are now offered in integration with other healthcare services on an ‘opt-out’ basis, the most successful example being the testing of pregnant women. Novel approaches make testing more accessible, including point-of-care tests, outreach testing and self-testing kits.

There remain considerable challenges. Globally, men are less likely to be offered or to accept an HIV test, and masculine norms may dissuade men from taking up testing. Younger people are also less likely to get tested due to unwelcoming healthcare facilities, and in some instances requiring parental consent for testing. Key populations such as gay men may still be dissuaded from testing due to fear of discrimination.

The second ’90’: receive treatment

At the end of 2017, 79% of people diagnosed with HIV received treatment. To achieve the 90% target, two things must happen: people with new diagnoses must be linked to care, and then they must be kept in care. The first of these is perhaps simpler, and, increasingly, diagnostic services are linked to rapid initiation of cheap and effective antiretroviral treatment. The second is a trickier proposition: the same barriers that may dissuade individuals from seeking testing may also affect their engagement in care, such as fear of stigma, discrimination or loss of income via attending care facilities.

The third ‘90’: achieve viral suppression

At the end of 2017, 81% of people receiving treatment for HIV had suppressed viral loads. With modern antiretroviral treatment, the main reason for treatment failure is non-adherence to therapy. Treatment failure must be detected early to prevent emergence of resistance, and this depends on readily available viral load measurement. The question of adherence will be the final frontier in HIV medicine and reaching the third ‘90’. This challenge is much less attractive than the quest for a cure or a vaccine, and far less likely to lead to a Nobel Prize. The reasons people who are in care do not take their medicines are myriad, and often defy the rationalism of a scientist. There are many proposed technological solutions, for example electronic monitoring systems to detect non-adherence, or text-message reminders. However, there is unlikely to be a ‘magic bullet’, and as with prevention, the winning formula will likely need to address underlying structural factors also.

The future

Moving forward, we must remember that the great successes of the global community in fighting HIV to date have hinged on protecting and promoting human rights. It is easy to assume that international progress in human rights will continue unabated, and HIV treatment and prevention programmes will continue to flourish in this environment. However, as our world sees a resurgence of populism, nationalism and isolationism, we must not forget the utmost importance of respecting the rights of the most vulnerable individuals in our society in effectively fighting HIV.

Paul Hine

Tropical and Infectious Disease Unit, Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospital Trust

[email protected]

Twitter: @doc_phine

Paul Hine is a Specialist Registrar in Infectious Disease and General Medicine at Liverpool Royal Hospital. He also works with the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group developing evidence synthesis.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

I’m extremely fortunate to work with amazing and inspirational teams in Liverpool Royal and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

How did you enter this field?

I have always been interested in both public health and hands-on clinical work – infectious diseases is a great specialty to combine these things!

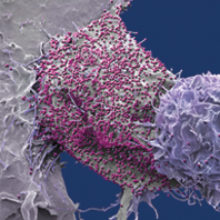

Images: Coloured scanning electron micrograph of a 293T cell infected with HIV (pink dots). Magnification x8000 at 10cm wide. Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library.

Blood test cassette, positive result. Cordelia Molloy/Science Photo Library.