An interview with Fleming Prize winner Professor Jane McKeating

Issue: Fleming Prize Winners

20 October 2020 article

Jane McKeating is Professor of Molecular Virology at the University of Oxford and won the Fleming Prize in 1995. Jane previously worked at the University of Birmingham, the Institute of Cancer Research and Lister Institute of Preventative Medicine. She has also worked in industry, as a Section Head of Anti-Virals at Pfizer Central Research, UK. Jane’s lab currently focuses on research into how specific host factors define infection with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) viruses. Three members of the McKeating research group, Peter Wing, James Harris and Xiaodong Zhuang interviewed Jane about her career.

What did you win the Fleming Prize for and what is your current research?

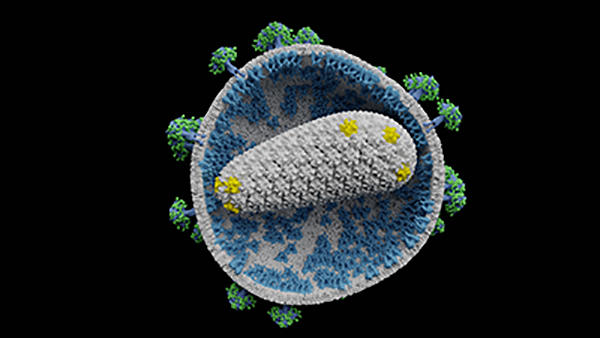

My Fleming Prize was awarded for my work on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) glycoprotein diversity and its impact on virus entry and sensitivity to neutralising antibodies. I’ve always been interested in understanding how the apparent chaos of viral RNA genomes can affect viral persistence and pathology, and whether viral sequences can inform us about viral pathogenesis and lead to new therapies. This question is so timely as we are now living through the COVID-19 pandemic and everyone is suddenly interested in RNA viruses!

Viral replication is defined by the cellular microenvironment, and oxygen sensing and circadian pathways are key players in regulating the cell. My lab currently works on hepatitis B and C viruses and how hypoxia-inducible factors and circadian components impact virus replication and sensitivity to anti-viral intervention. Developing model systems that better reflect in vivo physiology provides novel insights into the complex interplay between virus and host that can inform new therapeutic approaches.

What do you think is the most important skill you need to develop to become a successful scientist? Peter Wing, Postdoctoral Fellow

Firstly, I think you need to ask ‘big picture’ questions and always be driven by biology and not technology. Make sure you have the expertise and tools available to effectively answer your questions and be prepared to reformulate your questions to exploit your strengths. Secondly, science is a team sport and building good relationships with colleagues is really important. Thirdly, clear communication and generosity in sharing ideas helps engage new colleagues, and I believe it is key to a successful career in academia or the industrial sector.

Is HBV the most difficult virus when it comes to achieving a functional cure? James Harris, third year PhD student

Probably not; that ‘honour’ probably goes to HIV. Like HIV, HBV can integrate into the host genome. However, HBV integrants are generally defective and don’t produce infectious virus. The unintegrated HBV epigenome is the source of new virus particles and many labs are actively pursuing ways to destroy or to inactivate this small circular DNA molecule. As our understanding of the HBV life cycle improves, it is likely that we will develop therapeutic approaches that eliminate or silence this key replication intermediate. This would constitute a functional cure.

How applicable is the physiological oxygen model to other human pathogens; is it only relevant to viruses? James Harris, third year PhD student

Totally applicable to all microbial life – just consider how we classify bacteria as aerobic or anaerobic.

How important is it to focus your research early in your career? Is it ever too late to give something new a try? James Harris, third year PhD student

I would say it’s never too late and I’m still learning new things all the time; this is what makes research so addictive. However, I would always advise finding mentors and collaborators with expertise who can guide you to prevent ‘reinventing the wheel’.

What is the biggest change in science you have seen over your career? James Harris, third year PhD student

One very obvious change is the sheer quantity of publications and ever-increasing number of journals, making it a continuous challenge to keep on top of the literature. The electronic landscape of publishing now provides instant access to most journals – I can’t remember when I last visited a library. If I think back to how I designed experiments as a PhD student to how we work now – conceptually the thought processes underpinning ‘discovery science’ have not changed, but the technical approaches now available provide data faster and at a greater resolution.

What was the biggest challenge when you first became a Principal Investigator (PI)? Xiaodong Zhuang, Senior Postdoctoral Fellow

As a newly appointed lecturer, I was shown my lab and office and left to get on with it. Setting up a new laboratory, managing grant finances, coordinating multiple research projects and learning how to teach – quite a challenge with lots of mistakes made en route. Perhaps the biggest single challenge was managing my time to cover the many aspects of a PI’s role. Having a partner who understands and supports you in this exciting enterprise is essential.

What is the biggest challenge for a postdoc to become a PI and the best advice you can give? Xiaodong Zhuang, Senior Postdoctoral Fellow

To maintain your confidence and self-belief in the merits of your research plans and to be open-minded when the data disagrees with you. Very few postdocs obtain a fellowship on their first attempt, so perseverance is essential. In terms of advice, find a mentor (or even better two) whose opinion and guidance you trust even when it may seem negative at the time.

What did it mean to you to be awarded the Fleming Prize?

Confidence and affirmation that my research was valuable to the wider community.

Why does microbiology matter?

In the current climate I feel I don’t need to answer this question. We clearly need to understand all aspects of microbiology and pathogen-host interactions in order to be better prepared for the next pandemic.

Interviewers:

Peter Wing

Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Oxford, UK

James Harris

Third year PhD student, University of Oxford, UK

Xiaodong Zhuang

Senior Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Oxford, UK