Improving public understanding of scientific issues on a pandemic scale

Issue: SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19

12 October 2021 article

Most scientists have dabbled in science communication at some point in their careers. Now, in the midst of a pandemic, many of us are doing more than ever. But why do we do outreach? Personally, I find it really fun, but I think it’s a really important part of being a scientist. The public has a right to know what we get up to in the lab – particularly if we are publicly funded, (e.g. by government or charities). Another aspect is inspiring the next generation of scientists in order to make sure we will continue to have passionate and creative young people pursuing scientific careers and increasing the diversity in these professions.

A hugely important reason is to increase the scientific exposure and knowledge of our fellow citizens. Sensationalist news stories about science are relatively common, and were even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Stories such as the breakthrough of ‘three-person’ IVF or GM foods have caused many waves, often emotive ones, but the actual science behind these stories is often neglected. If the public had a good understanding of the scientific process or basic understanding of biology, these ‘controversial’ stories may have seemed less, well, controversial. The more scientific exposure we provide to the public, the better equipped the public will be in making decisions in everyday life – from decisions such as choosing a healthy diet and living more sustainably, to life-or-death decisions like consenting to medical procedures.

The way science has been communicated since the pandemic started has been vastly different from any other time in history. As a ‘new’ virus, there was very little data available on SARS-CoV-2 and any new data was quickly reported on by the media. The public was watching the science unfold in real time, often including preliminary or non-peer reviewed studies. This led to conflicting information being disseminated, preliminary data being presented as fact and a general sense of confusion around the science of the pandemic. In some instances, this sadly led to distrust and fear. I’m going to take two major topics of the pandemic – masks and vaccines – and will discuss how better outreach may have aided the public’s understanding of these areas.

Face coverings

Wearing of ‘face coverings’ became mandatory in indoor public places in the UK in the summer of 2020, with similar mandates appearing in other countries around the world. Prior to this, the public had been advised against wearing face masks for multiple reasons. Understandably, there were concerns that if the public started using masks, there would be further pressures on the availability of PPE for healthcare workers. There were also concerns that wearing masks would provide a false sense of security, potentially inducing wearers to engage in risky behaviours that would increase virus spread. There was also limited evidence that non-surgical masks reduced viral spread – not because this wasn’t true, but because this wasn’t a particularly widely studied area.

Many studies concerning masks prior to the pandemic were addressing very specific questions, for example efficacy of specialised masks in healthcare settings, or with particular attention to certain diseases (e.g. influenza). In addition, this is a practically challenging area of study due to difficulties in experimental design and ethical concerns of using human subjects.

Early on in the pandemic, due to a lot of pandemic planning being based on the influenza virus, there was a large emphasis on fomite transmission. People were advised to not touch their face, avoid touching surfaces and frequently wash their hands. Although this is sound advice, we now have mounting evidence that SARS-CoV-2 spreads predominantly via droplets and aerosols and, therefore, as we re-entered workplaces, public transport, school and other indoor environments, masks became mandatory.

This dramatic change in policy was met with confusion and, occasionally, anger. Why did the message about masks change so drastically? Simply put, the research showed that it was likely to be beneficial in preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

In the modern world, people want clear cut answers quickly. Scientists were questioned whether they were ‘wrong’ before on the matter of masks. And if they were wrong on this, what else were they wrong about?

In science, we know that all the knowledge we hold true isn’t necessary ‘true’, it’s simply the best explanation we have based on the evidence available to us at the time. When new research comes to light, we change our ideas and theories. Therefore, when data became available that masks were likely to significantly reduce virus spread, the policy changed. If the general public were more familiar with the scientific process, perhaps there would have been less backlash to this particular issue.

Vaccines

I am still, to this day, astounded and impressed that we had approved vaccines in clinical use just over a year after the virus had been identified. The amount of effort put in by huge multidisciplinary teams to realise this goal is astronomical. Yet many people are still distrustful of them.

There is confusion as to why we have a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2, a virus first identified in 2019, but we still don’t have a vaccine for viruses we’ve known about for a long time, e.g. HIV. This, as many readers will be aware, is down to the many complex biological differences between these different viruses; how they spread, infect and evolve. The general public are not virologists, and at the start of the pandemic many wouldn’t have known the differences between viruses and bacteria, let alone the many types and pathologies of different viruses. The general public can’t be expected to have a profound and deep understanding of virology, but if most had a good understanding of biology in general, these misconceptions and concerns would have been easily mitigated.

A major reason for vaccine hesitancy is the speed at which the vaccine was developed, tested and approved. Most people who don’t work in clinical trials research probably don’t have a particularly good understanding of the process for a new vaccine approved for clinical use. Clinical trials are often long and laborious, but most of this time is not spent on the actual testing of the vaccine, it is spent liaising with medical staff, recruiting volunteers and applying for further funding for each stage of testing. However, in the pandemic, huge chunks of time were saved by multiple research teams coming together, funding being rapidly approved and a monumental national effort in patient recruitment and clinical coordination. If the public were better informed of how clinical trials are conducted, perhaps this would have alleviated some of the worries people had in terms of the speed at which they have been conducted this past year.

Finally, an often-overlooked part of why outreach is important is that scientists are normal people too. Too many people imagine scientists to be eccentric Einstein-types, detached from society. As most readers will know, this is far from true, but it didn’t stop a lot of hate being directed at scientists for supporting strict virus-control measures, whether this be abusive comments on social media or fully fledged protests. We have families we want to visit too, pubs and cafes we love to frequent, activities we love to participate in – just because we advised against visiting the places and people we love, didn’t mean that we didn’t miss these aspects of our ‘normal’ lives.

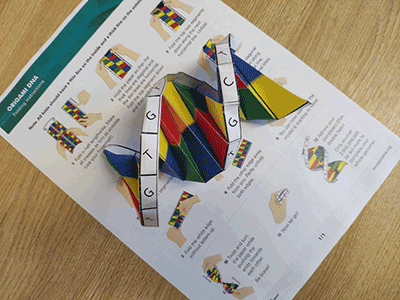

For many of us, this pandemic has been a crash course in science communication, but if we had sown the seeds of science outreach further and more regularly, we may have mitigated some of the misconceptions and confusions that arose throughout this global pandemic. Our scientific studies and findings are useless without communicating them outside our research groups. In order to have an impact, we share our findings to the scientific community, through talks and publications, but often no further. Perhaps now is the time we include journalists and the public in this process on a regular basis. Many publications support the inclusion of a lay abstract in addition to the standard scientific one. Some researchers do excellent explainers of their work to the public, such as through Twitter threads, YouTube videos – even colouring books! I personally write articles in The Conversation, who publish lay articles for general readers that are heavily utilised by media to report on these stories; The Conversation regularly contact the authors for further pieces. In all of these methods, we, the scientists, directly communicate our scientific findings to the public, and with more exposure, we can, hopefully, form a world where everyone thinks more scientifically, and sensibly.

Further reading

Davies A, Thompson KA, Giri K, Kafatos G, Walker J et al. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic? Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013;7:413–418.

Greenhalgh T, Jimenez J, Prather KA, Tufecki Z, Fisman D et al. Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet 2021;397:1603–1605.

The Conversation. HIV/AIDS vaccine: why don’t we have one after 37 years, when we have several for COVID-19 after a few months? 2021. theconversation.com/hiv-aids-vaccine-why-dont-we-have-one-after-37-years-when-we-have-several-for-covid-19-after-a-few-months-160690 [accessed 17 May 2021].

Grace Roberts

Wellcome-Wolfson Institute of Experimental Medicine, School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences Queen’s University Belfast, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK

Grace Roberts is a postdoctoral research fellow working at the Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine at Queen’s University, Belfast. Her current research investigates the links between respiratory syncytial virus infection and asthma development, funded by the Wellcome Trust. Grace has also supported the SARS-CoV-2 drug discovery project at Queen’s University.

How did you get started in scientific outreach?

The first time I heard of ‘outreach’ as a term and a concept was when I was a technician working in cancer pathology in Leeds. Cancer Research, who funded many research projects in the centre, had an annual visit day where any patients who had involvement in the research (e.g. donated tissue samples) could visit the centre for a day of talks and a tour around the labs. It was well received by the attendees, and I thought it was a great idea! Then when I went on to do my PhD, I got involved in outreach through the annual Leeds Festival of Science, which introduces school children to hands-on science, where I helped design and run a stall about microbiology and the importance of handwashing. I loved how what seemed like basic science to me induced such enjoyment and intrigue in young minds. Since then, I’ve been regularly involved in outreach and have seen its importance in inspiring the next generation, but also informing the general public of scientific research.

What advice would you give to others who want to get started in outreach?

Definitely ask someone who has some experience who can help you develop your ideas. Hands-on experience of what worked well in the past is valuable to designing new outreach activities. When designing a new activity, I think the two most important things to establish are your main message and your target audience. Once you have established your ‘main message’ for your outreach activity, make sure every aspect of your activity contributes to the communication of the message, regardless of the outreach format. When considering your target audience, it’s important to consider things such as the audience’s age (which can affect what is appropriate to include in the activity) and prior knowledge of your subject. Importantly, however, never underestimate or patronise your audience – often, I have found non-scientists to be fully capable of understanding vastly complex concepts, they often just lack the technical vocabulary that scientists use every day.

Image: Drazen Zigic/iStock.