Imitation game: evolutionary parallelisms between Bordetella pertussis and B. parapertussis

Our names are Dr Valérie Bouchez and Prof Sylvain Brisse, and we study Bordetella genomics in the Biodiversity and Epidemiology of Bacterial Pathogens (BEBP) Research Unit at Institut Pasteur in Paris, France. Our research group also hosts the French National Reference Centre for whooping cough and Other Bordetella infections. We are interested in the diversity, evolution and epidemiology of bacterial pathogens and in the links between the genotypic and phenotypic diversity of the strains within particular bacterial species, among which the agents of whooping cough. We report on a recent work performed in collaboration with colleagues in Spain and the USA.

The tale of two pathogenic bacteria

Whooping cough is a severe respiratory disease caused by two closely related bacteria: Bordetella pertussis (Bp) and the lesser-known Bordetella parapertussis (Bpp). While Bp takes the spotlight as the main agent of whooping cough, Bpp also contributes significantly to the global burden of the disease but remains understudied because it is under sampled, under-reported and often overlooked.

The story of how vaccines have shaped Bp's evolution is well documented. When acellular pertussis vaccines replaced older whole-cell vaccines in the 1990s across industrialized countries, Bp populations adapted to these novel vaccines, which contain only 3 to 5 (depending on the brands) purified antigens from Bp: pertussis toxin (always included), and various combinations of filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin (PRN), and fimbrial proteins. Over time, pertactin-deficient Bp strains emerged and spread rapidly, dominating in countries using acellular vaccines just before COVID-19 arose. These PRN-negative Bp strains appear fitter, a classic case of pathogen adaptation to vaccine-induced immunity, and may even cause milder disease, which would imply that the PRN-containing vaccines would drive Bp populations towards lower virulence.

What about the neglected Bpp?

Here's where our story gets interesting. The two bacteria Bp and Bpp are phylogenetically related, ecological competitors, and both exclusively infect humans. Pertussis vaccines were designed exclusively against Bp, with no consideration for Bpp. Nevertheless, Bpp shares two key antigens with Bp, FHA and PRN. This raised a compelling question: Could vaccination against Bp have driven evolutionary changes in Bpp as well? While isolated reports had documented pertactin disruptions in some Bpp strains, no comprehensive population-level analysis had been conducted.

An international collaboration spanning nearly a century of clinical microbiology work

To answer this question, we joined forces with the teams of Dr. Juan José González-López at Vall d'Hebron Hospital in Barcelona, Spain, and of Dr. Michael R. Weigand's at the CDC in Atlanta, USA. Together with our reference laboratory, these three groups were able to assemble a unique collection of 242 Bpp isolates from France, Spain and the USA, countries that have been using pertussis acellular vaccines over the last 20 to 30 years. These isolates were derived from clinical infections that occurred over 82 years (1937-2019), and this timeframe was crucial as it covered the pre-vaccine era, the whole-cell vaccine era, and the acellular vaccine era, allowing us to trace Bpp's evolution across these different vaccination periods.

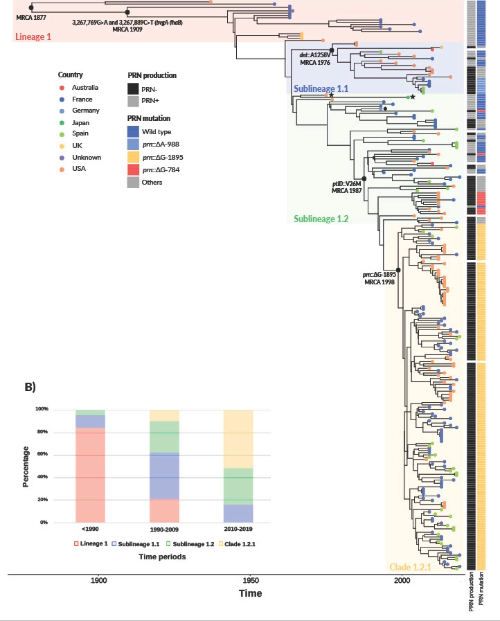

The timing of our study turned out to be fortuitous. When we began this project five years ago, the COVID-19 pandemic began. Remarkably, both Bp and Bpp virtually disappeared during lockdowns probably because of mask-wearing and social distancing both reducing transmission of these respiratory pathogens. By focusing on pre-2019 isolates, we captured the complete evolutionary history of Bpp before this unprecedented reduction of circulation. Using whole-genome sequencing and Bayesian phylogenetic analyses, we reconstructed Bpp's evolutionary history, with a particular focus on vaccine antigen genes and virulence factors evolution.

Striking evolutionary parallelisms

Our findings revealed remarkable parallelisms between Bpp and Bp evolutionary changes:

- Similar timelines and evolutionary rates: Previous studies estimated that modern Bp lineages emerged around the late 18th to early 19th century. Our analysis dated Bpp's most recent common ancestor to around 1877, making it slightly younger than Bp. Even more striking, Bpp's evolutionary rate (2.12×10⁻⁷ substitutions per site per year) was remarkably similar to Bp's previously reported rate (2.24×10⁻⁷) indicating that these two independently evolved human-adapted pathogens are evolving at nearly identical speeds.

- Early adaptation to humans: We discovered two mutations in the regulatory region between the bvgA and fhaB genes that occurred around year 1900 and became fixed in modern Bpp populations. This region is critical as it controls the master virulence regulator BvgAS, which orchestrates the production of multiple virulence factors including FHA and PRN. Intriguingly, this same intergenic region also shows extensive evolution in Bp, suggesting that modifications of this regulatory region was crucial for both pathogens' adaptation to their human host.

- Vaccine-driven pertactin loss: Here's where the story becomes most compelling. We identified 18 different disruptive mutations in the pertactin gene across Bpp populations. The most frequent one is a single nucleotide deletion (prn::ΔG-1895) that arose around 1998, shortly after acellular vaccines were introduced, and now appears in 73.8% of post-2007-2019 Bpp isolates. This observation mirrors what happened in Bp: multiple independent mutations arising after acellular vaccine introduction, all leading to the loss of pertactin expression. This convergent evolution strongly suggests that pertactin expression became disadvantageous for Bpp in vaccinated human populations, even though the vaccines weren't designed against Bpp.

- Unexpected genetic conservation: Gene clusters encoding pertussis toxin and fimbriae showed no evidence of decay, despite not being expressed in Bpp. Why maintaining these genes? This hints at the intriguing possibility that these "silent" genes might be reactivated in some conditions to be discovered in the future.

Why this matters

Perhaps most fascinatingly from an evolutionary biology perspective, our study reveals how two distinct pathogens having independently evolved from a common ancestor to colonize the same host followed strikingly similar evolutionary trajectories. They emerged as human pathogens within decades of each other during the Industrial Revolution. They evolved at nearly identical rates. They both modified the same critical regulatory region early in their adaptation to humans. And most recently, they both rapidly shed the same vaccine antigen when acellular vaccines created new selective pressures. While bystander evolution has been documented for antimicrobial resistance (where antibiotics targeting pathogens inadvertently select for resistance in commensal bacteria), our study demonstrates an example of "bystander evolution" of a non-target organism evolving in response to vaccination targeting another species, although in this particular case, the two species are closely related.

Looking forward

Bpp may be the "other" agent of whooping cough, but it's far from an innocent bystander. Our work demonstrates that this neglected pathogen deserves closer attention not only for its own public health importance but also as a natural experiment in evolution, revealing how vaccination can reshape entire bacterial populations, even those it doesn't directly target.

In addition, following the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions in 2022, Bpp was remarkably the first Bordetella species to resurge in France, the USA, Colombia, and Mexico. Could the evolutionary changes we documented, particularly widespread pertactin loss, have contributed to this rapid comeback? Our large genomic dataset, gathered thanks to the collation of three large biocollections, provides the baseline for investigating this question. The story of Bpp's evolution is far from over and we'll be watching closely to see what happens next.