Tracking Vibrio paracholerae: The “hidden” bacterial species

Hello world! I’m Sergio Morgado, a postdoctoral research associate exploring the genomes of a wide diversity of bacterial species. I work at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, also known as “Hell de Janeiro”, thanks to the heat and “intensity” of both the city and the science done here.

Among the many bacteria studied by my research group, Vibrio cholerae has a particularly long history. Our work on this species goes back more than 30 years and has focused on identifying genetic lineages (think of them as different “tribes”), as well as antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in isolates associated with cholera-like disease in Brazil. Although V. cholerae is ubiquitous in aquatic environments, only a subset of its lineages is capable of causing disease.

While exploring V. cholerae genomes isolated from cases of bacteremia (bloodstream infections), we stumbled upon something unexpected. During phylogenetic analyses (essentially reconstructing the evolutionary history of these genomes), we noticed that a small group of genomes clustered apart from the rest. Further genomic analyses confirmed what initially seemed unlikely: these genomes did not belong to V. cholerae at all, but instead to a recently described sister species, Vibrio paracholerae.

At first glance, this might sound like a minor taxonomic detail. In reality, misidentifying a clinically relevant species can introduce significant taxonomic and epidemiological bias, with direct implications for disease surveillance, outbreak investigation, and even treatment strategies.

This observation led us to a broader question: if we were able to detect V. paracholerae within a relatively small set of genomes originally classified as V. cholerae, how many more misclassified genomes might exist in public databases? To address this, we expanded our analysis to more than 13,000 V. cholerae genomes available in GenBank, applying multiple complementary genomic approaches.

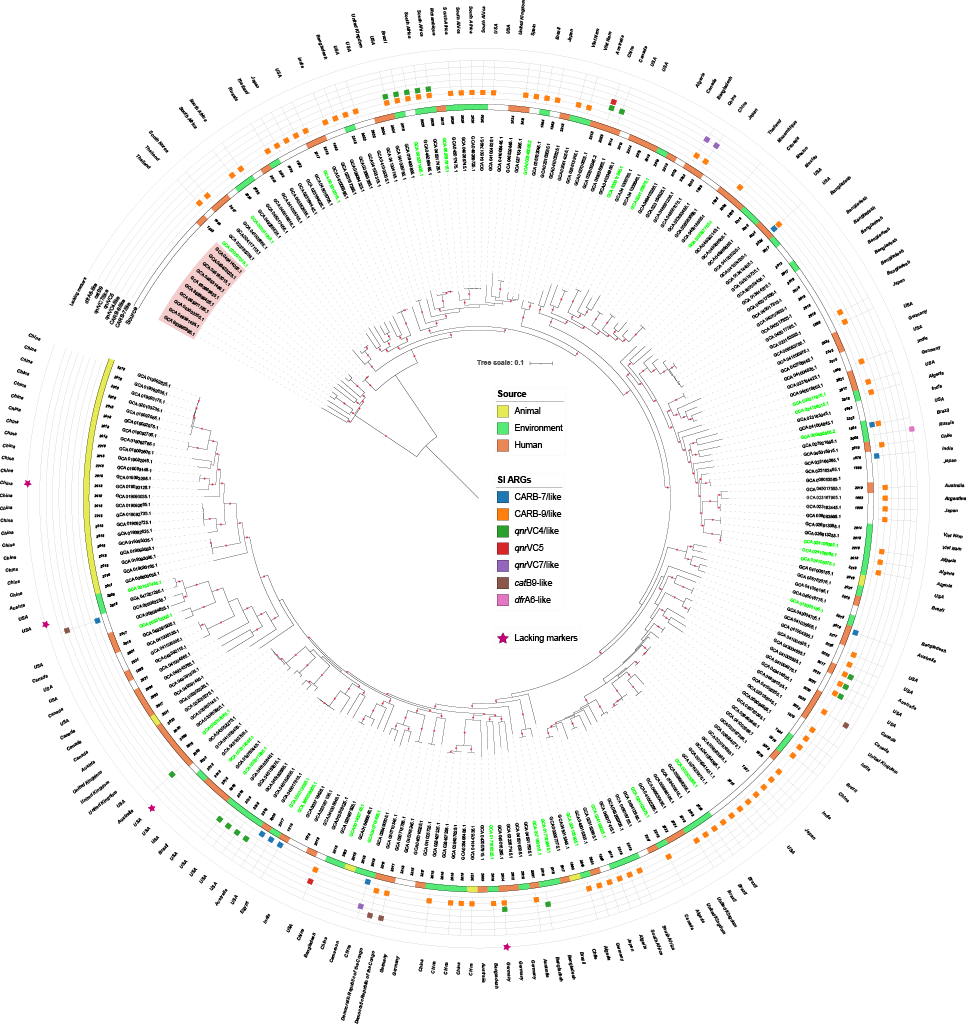

The results were striking. We identified 190 genomes that were in fact V. paracholerae, representing roughly 2% of the dataset. This finding dramatically increased the number of available V. paracholerae genomes, which previously stood at only 32 non-redundant entries in GenBank. With this expanded dataset, we were able to explore the epidemiology and ecology of the species in much greater depth.

Our analyses showed that V. paracholerae persists across diverse ecological niches and, importantly, can act as a reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes, much like V. cholerae itself. This suggests that its role in microbial ecology and public health has likely been underestimated, largely due to years of misclassification.

We also explored whether it would be possible to define clear genetic markers to distinguish V. paracholerae from V. cholerae. Although we did not identify a single “gold-standard” marker gene, we did find five putative genes with high sensitivity and specificity for discriminating between the two species. These markers represent a tool for diagnostic applications and epidemiological surveillance.

Taken together, our findings reveal an unsuspected epidemiological scenario for V. paracholerae, reinforcing the need to consider this species in clinical monitoring and public health strategies involving Vibrio.

One final clarification is important. V. paracholerae was only recently characterized, meaning that earlier genomic studies had no reason to suspect its existence. As a result, many of its genomes were understandably classified as non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae (that is, outside the pandemic lineages). Even today, it is likely that some bacterial species we name will be reclassified in the future. Taxonomy, like science itself, is dynamic: as new technologies and analytical tools emerge, long-standing assumptions can, and should, be revisited.

How many other ‘hidden’ species might be waiting in public databases?