Why wildlife sampling is hard

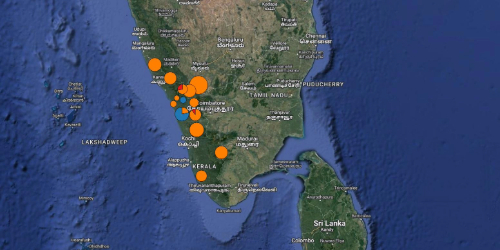

This project was an exercise in extreme field science. It was funded and carried out at the height of India’s terrible SARS-CoV-2 epidemic with sampling taking place in Kerala, India in 2020-2022.

The field sampling team are part of the Kerala State Government Forestry Service and are the only veterinary team covering a very large area of mountainous tropical forest in southern India. It’s a beautiful area - the Western Ghats mountain range are listed as a UNESCO world heritage site and biodiversity hotspot.

Parts of it are also very inaccessible and some of the animals we sampled are dangerous. The team had to deal with SARS and deaths in extended families. They also had to battle extreme weather conditions and major flooding in Kerala which affected our ability to collect samples. In the case of one species of bat, the floods washed away the known roost sites meaning we missed our sampling targets. The species may now be locally extinct. The field team’s day job also involved dealing with tigers and elephants that raid villages. Tragically one capture went very wrong over the course of this project and members of the team were injured and killed. The samples and data don’t come out of nowhere and this one was harder than most.

The scientific parts of this project, negative results or not, are important. Despite the scale and impact of SARS-CoV-2 and animal spillovers there are still whole countries where we have no idea what the situation is with cross species transmission. Some of the species we sampled, like macaques and civets, are high risk for SARS-CoV-2. They often live in towns and villages, interact with people and can be infected experimentally. So, it was pretty critical to know if they were being infected in the field. Fortunately for everyone, the SARS-CoV-2 screening was negative. Interestingly, we didn’t find SARS-like viruses in the horseshoe bats (their natural hosts) in India.

This is really different to when similar sampling is done in South East Asia and different to what we found in a companion study of horseshoe bats in the UK. This work adds to a growing picture that there is something particular about horseshoe bats in border regions in southern China facilitating repeated Sarbecovirus spill over. Sometimes knowing which animals are not infected or whether experimental infections are replicated in real life can be just as critical in disease prevention planning as the more headline grabbing reports and this study puts another piece of that puzzle in place, one collected with heroic effort.

Image: iStock/f9photos