Could ‘killer yeasts’ be the key to treating drug-resistant Candida glabrata?

25 June 2019

Some species of yeast produce a killer toxin that could be used to treat drug-resistant yeast infections. Researchers from the University of Idaho have identified a naturally-occurring toxin that kills the important fungal pathogen Candida glabrata.

Candidiasis is the name given to infections caused by any member of the Candida genus. C. glabrata is one of the most common causes of candidiasis and is highly resistant to most antifungal drugs, meaning treatment options are seriously limited for those infected with the pathogen. In Europe, C. glabrata is responsible for up to 30% of candidiasis infections, and in the USA as many as 40% of Candida infections are due to C. glabrata.

In the hunt for new ways to treat C. glabrata, research conducted by Lance Fredericks tested the value of toxins produced by the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. S. cerevisiae is often used in baking and beer production, but has also been known to produce killer toxins that slow the growth of many fungal pathogens. The research group assessed whether these toxins could prevent the growth of yeasts in the Candida genus.

According to Fredericks, new treatments for C. glabrata infection are desperately needed. He said, “Treatment of C. glabrata infection uses drugs that can cause a wide variety of undesirable side-effects, which can be severe when combined with other medications. Additionally, C. glabrata is increasingly resistant to these antifungal therapeutics.”

During their research, the group tested the activity of 90 strains of S. cerevisiae against several strains of C. glabrata. They found seven of these 90 strains produced toxins capable of killing all known strains of drug-resistant C. glabrata. Fredericks said this result was unexpected: “Previous data on the susceptibility of C. glabrata to killer toxins has been reported in the literature. However, the scope of these studies was somewhat limited, and they only tested a few representative strains of C. glabrata. We were surprised to find that all of the 101 strains of C. glabrata that we have so far challenged are susceptible to killer toxins. Importantly, this includes clinical isolates of C. glabrata that are resistant to multiple classes of frontline antifungal therapeutics.”

Fredericks hopes that these killer toxins can be used to develop new antifungal therapies to treat otherwise-untreatable C. glabrata infections. He said, “We have already conducted some tests to simulate the application of killer toxins under physiological conditions and have been encouraged to find that some of the killer toxins are active at human body temperature. However, we are planning many more experiments to test the feasibility of using killer toxins to treat infections by C. glabrata.”

This new knowledge could be used to develop therapeutic precursors which can be used to ‘weaken’ fungal infections ahead of administering antifungal drugs. This would make fungal infections easier to clear and reduce the likelihood of resistance developing.

This research was conducted in collaboration with Cooper Roslund, Angela Crabtree, and Emily Kizer under Dr Paul Rowley in the Rowley lab at the University of Idaho.

Lance Fredericks will present his data at the Microbiology Society Focused Meeting: British Yeast Group: Discovery to Impact. His poster, ‘Inhibition of drug-resistant Candida glabrata by killer toxins produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae’ will be available to view from 26-28 June at the County Hotel, Newcastle.

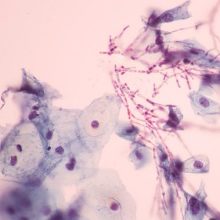

Image: iStock/arcyto.