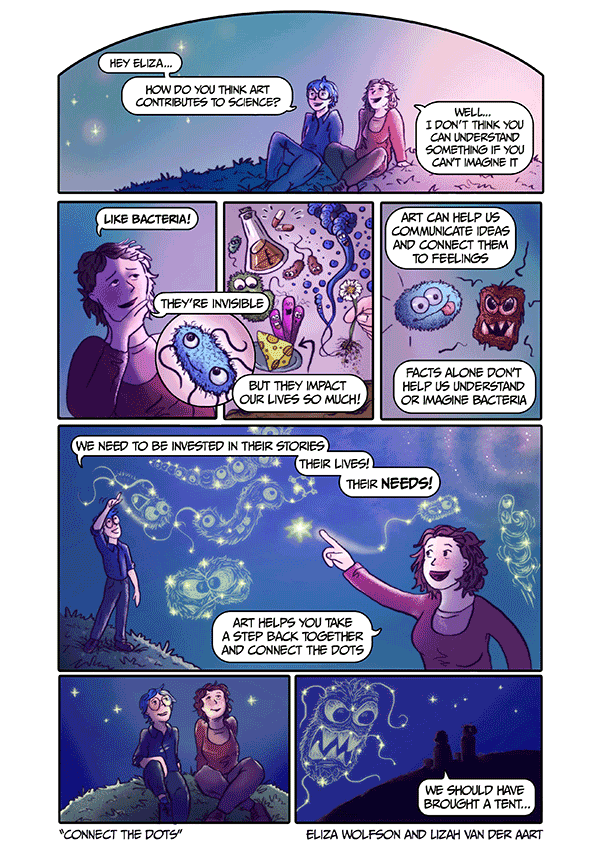

Science art: it’s all about connecting the dots

Issue: Engaging Microbiology

17 May 2022 article

‘Bacterium’. We all immediately have a vision in mind. Perhaps it’s an E. coli with pili and flagella, maybe a Bacillus forming a spore, a mat of Streptomyces complete with aerial hyphae – or even a twirling spirochaete. A few more words will allow us all to share this same idea of ‘bacterium’.

You, a reader of Microbiology Today, are probably lucky enough to know a lot about different bacteria and their ecology. Perhaps you have studied snapshots of their lives or even watched them move. Most people don’t have the equipment or know-how to do this; bacteria are generally too small to see without specialist equipment. Yet how can you really imagine a bacterium if you have never seen one?

This is where science art, or ‘sci-art’, comes in. By showing, rather than telling, we can bypass the jargon of description – what do they look like? Allowing us to move on to the fun part: what are they doing? What’s their story? What are their needs?

Sci-art is a great tool for telling stories about and around science, rather than just explaining the science itself. These stories can help us to explore the ‘so what?’s of microbiology together, by creating a basic shared visual language. Science stories are not just made of language, visual or otherwise, but also emotion. You don’t have to understand how antimicrobial resistance occurs to feel empathy for a cartoon character who is frightened by it. Adding layers of emotion through narrative can soften the blow of some of the scarier ‘what if?’s, for example, with humour. All this allows us to delve deeper into how microbiology impacts the world or the people around us and connect the dots.

A wider appreciation and connecting the dots with microbiology is now more important than ever. As we live through this pandemic, we have to make decisions about microbiology every day. We weigh up the risks that different variants of an airborne virus pose to us, our loved ones and our communities, against the mitigations available to us. Again, a reader of Microbiology Today may have a firm basis to make those decisions. However, many people without an understanding of infection processes and control or vaccination are having to make tough calls, often in a landscape of inconsistent and ever-changing public health messaging.

Sci-art has given people a shared picture of what SARS-CoV-2 looks like; the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s familiar grey virion with red spikes is etched into the collective memory, an icon for this time and our shared danger. When talking heads discuss spike protein mutations, most people know they’re talking about ‘the red bits’. Sci-art has also helped share how we can protect ourselves and each other; it was no accident that early on in the pandemic there was a global call from the United Nations for art to help spread public health messages and unity. This art was about communicating emerging scientific and health information, quickly, simply and emotively.

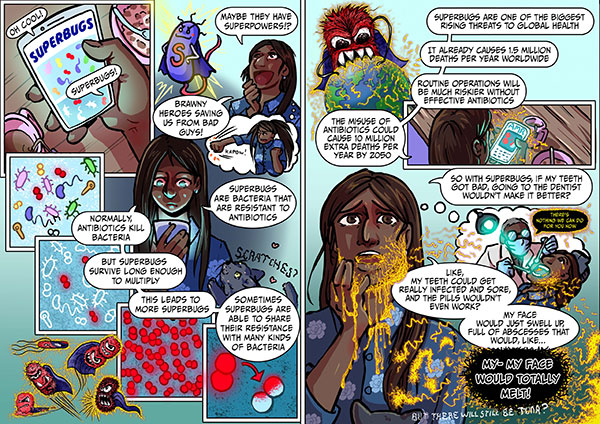

This need to communicate microbiology more widely won’t go away as we ‘learn to live with’ COVID-19. Another silent pandemic is growing all the time, into something that poses a real risk to our way of life (if climate change doesn’t get us first): antimicrobial resistance, or AMR. It is already killing more than a million people a year and is estimated to kill ten times that in 20 years. The scale of the problem is too big to take in by looking at those cold hard numbers and too awful. Attempting to shock people into action with factual prediction appears to have the opposite of the desired effect, as shown by how the ‘global warming’ discourse progressed in the 1990s. It becomes easy to dismiss the whole thing because it seems that it’s too big to do anything about, and too far in the future.

A proposed solution to this problem is to approach science communication from a place of empathy, rather than facts. By showing an audience what AMR is with sci-art, we can move past boundaries like jargon. For a brief moment, the difference between antibiotics and antimicrobials doesn’t matter – only that the bad guy is or isn’t slain. Instead of starting with bare facts, we can use sci-art and embed them into a narrative, starting with empathy and only then moving on to the explanation once someone is receptive to it.

Sci-art not only gives us the tools to visually explain AMR but also to relate, engage and empower people around these issues. Sci-art can make AMR more relatable by using characters we can become invested in. Done well, these characters can pull us into their world. They can take us through how we might feel in the face of ‘what if antimicrobials stop working?’ and move past it, along their narrative arcs. By sharing characters that go through these emotions with an audience, we validate their own emotions. Also, unlike the reality of factual predictions of doom, if you don’t do x, y or z, a narrative arc can build towards a resolution. This can be used to empower the audience. They can be taken through a rollercoaster of plot and emotions so that at the end they are left understanding how they feel about AMR – and perhaps even what they can do to help.

Sci-art is often not merely illustrative, but a storytelling device. The story or central concept behind sci-art is key and often determines its entire structure. This is particularly the case when using sci-art in comics. For example, when making ‘Connect the dots’, the first thing we did was to hone the message in the speech bubbles and work out their placement. This may seem counterintuitive, as comics appear to be all about illustrations. Yet without proper structure, pacing and word choice for the narrative, the story does not make sense. As with other versions of storytelling, sci-artists have a toolbox that they can use. Like a hook to catch the reader’s eye, or leaning heavily on emotions and expressions to create drama and finally: humour – either a visual gag or a joke in the text. There is a good chance that the reader doesn’t initially care about the explanation of AMR in a comic, but becomes invested in the cat that tries to get the main character’s attention. Yet while enjoying this, they are creating positive associations with AMR, science and microbiology.

The real beauty of using art to communicate scientific concepts is that there are a number of technical devices that the artist can use to affect conscious and subconscious emotion, which influences how an audience engages with the science. The simple concepts of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ can be communicated implicitly by choice of colour, shape, composition and quality of line. For example, in our comic, ‘Connect the dots’, there is a ‘good’ and a ‘bad’ bacterium. The ‘good’ is easy to recognise with big googly eyes, a soft, round shape and pastel colouring. The ‘bad’ has sharp edges, big teeth, angular lines and blood-red colouring. We don’t have to tell you which one is good or bad, you already know via these visual shortcuts. It doesn’t have to stop at good, bad, happy or sad either – emotional weighting can be applied to any scientific concept. Of course, this is not new; we are simply leaning on long-standing trends in visual storytelling. We are using the associations that existing comics, animations and illustrations have already created to tell stories about science.

In short, our goal as science artists is to help create a shared vision that we can all engage with, as it can be hard to understand what you cannot see inside your head. Perhaps this sounds superfluous – we just draw pretty pictures! However, these pictures can help shape the narrative and image of science, and how it is discussed in wider society. Sci-art is a bit like a superpower: with this tool, you can influence what someone imagines and feels when they hear this word: ‘Bacterium’.

Eliza Wolfson

Freelance Scientific Illustrator

lizawolfson.co.uk

[email protected]

@eliza_coli

Lizah van der Aart

Science Artist and Science Communicator

lizahvanderaart.com

[email protected]

@LizahvdAart

Eliza Wolfson and Lizah van der Aart are microbiologists and science artists who occasionally team up to make comics together. They are currently working on crowdfunding a set of comic anthologies about AMR – check out @AMR_comics for more information!

What inspired you to work in science art?

Eliza: I’m a compulsive doodler and during my PhD I used short incubation periods in the lab to draw cartoons on the whiteboard. This led to me making figures for my supervisor. After a while it seemed that this was where I was really useful in microbiological research and there was a need for someone like me to do this for other scientists.

Lizah: I have always loved to draw and make art, but it took me a long time to combine art with science. For me, art was always an escape from my busy academic life. But when one of my illustrations about handwashing went viral at the start of the pandemic, I saw the massive impact illustrations can have on people and that there is room for me in that industry.

What part of your job do you find most challenging?

Eliza: I get stage fright! The progress of an illustration isn’t always linear; sometimes the magic bit happens right away and you can see where it is leading, and other times you have to keep trying things, just like in the lab. I’m always a bit nervous until I can see that I have solved the creative problem.

Lizah: Conceptualising the first idea to tell a story. Once there is an idea, the drawing is easy, but going from a blank page to ‘something’ is always the hardest part for me.