The GermBugs collaboration: story-based microbiology teaching to engage and inspire undergraduate medical students

Issue: Engaging Microbiology

17 May 2022 article

With 30% of patients in hospital on antibiotics, training medical students in medical microbiology is important. However, the time available for microbiology teaching within undergraduate curricula has been squeezed from a time when students experienced rich learning in microbiology laboratories to being taught by experts in lectures. Despite comprehensive curricula, students have reported not remembering lecture-based teaching in subsequent years. Furthermore, microbiology is a subject that is often entirely new to students and, being heavy on new Greek and Latin terminology, can be difficult for students to access. We believe some students may learn microbiology better from alternative learning opportunities.

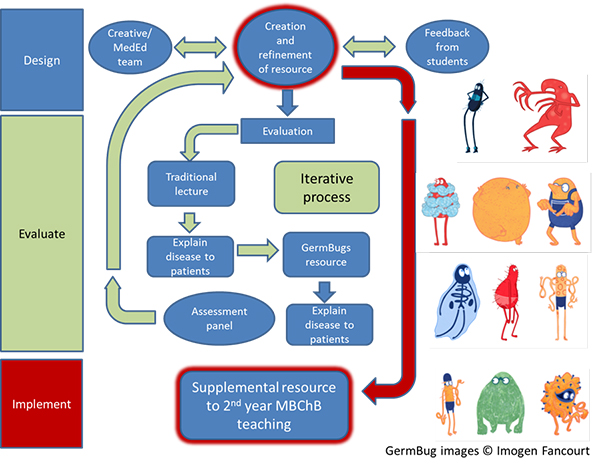

Based on our experience as parents who read children’s stories, and as doctors, where we commonly personify pathogens, e.g. we battle nasty bugs, we recognised that bacteria could easily be transformed into story characters. We knew from previous medical education research that stories can be memorable, provide scaffolding and reflect ways that humans have always learned. Therefore, we developed stories about bacterial organisms, called the GermBugs. We invited medical students, art graduates and learning technologists to join us in co-developing the GermBugs to make microbiology learning more engaging and accessible. The GermBugs resource is an online, interactive, audio-visual resource with varying levels of complexity which is suitable for independent learning. We evaluated medical students’ experiences of the GermBugs prior to it being implemented this academic year. This article tells the story of the GermBugs development process so far, including obstacles and learning along the way, as summarised in Figure 1.

Year one – Development

We designed a GermBug story for the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus based on a character called the Green Explorer, who is green given all that snot in the nose (perhaps you knew S. aureus lives in the nose already, but hopefully you’ll remember more easily now). In the story, the Green Explorer is picked from the nose and put down in an open wound where an infection follows, as shown in the picture on page 18.

We presented the story to a small group of medical students for feedback. Most resisted the resource, anticipating that other medical students would find the illustrated story patronising. While some students recognised some potential in the resource, they were focused on how it would relate to their pass or fail examinations. Only one student, then in their final year, saw potential in the resource to give language which could aid communication with patients. Frustrated that our new resource was not wholeheartedly welcomed, we decided we needed to learn more.

We recruited two intercalating medical education students to undertake more detailed research about learning through the Green Explorer. One student (Priyanka Gandhi) sought to test whether the Green Explorer led to improved microbiology knowledge, while the other student (Muhammad Noor) explored what influenced first-year students’ reactions to the Green Explorer.

Through the first study, we learned that administering a multi-choice question assessment after reading about the Green Explorer may not have tested what the resource had taught above lecture-based teachings, such as understanding infection processes. The second study further enhanced our understanding of the earlier group’s reactions. The Green Explorer was most valued by students who had previously used the arts to enhance their learning. Other students had relied on memorisation of facts and ‘past papers’ and expected to continue learning in this way at medical school. Learning through stories did not fit these students’ expectations of discipline, formality and ‘seriousness’ in medicine. Students also fed back to us that they would engage with the Green Explorer only if it related to a formal learning objective and exam questions were based on the content. They also suggested the story should be given alongside traditional resources, to supplement but not replace traditional lecture-based education.

This research led us to think more carefully about how the GermBugs should be introduced to students.

Establishing its credibility and clinical relevance was the next challenge.

Year two – Pilot and Evaluation

The following year, we had the opportunity to work with another intercalating medical education student, Lucy Pangbourne, to trial an improved GermBugs resource. This time we recruited clinical medical students from years 3–5 to try out the Green Explorer and apply it to patient-based scenarios about infection.

First, students accessed a traditional-style recorded lecture on S. aureus and were then asked to explain aspects of the process of infection to a patient. Second, they were invited to engage with the Green Explorer and explain the process of infection to a different patient. Students were then invited to compare the two experiences. The students’ explanations were recorded and later assessed by the student researcher, a consultant microbiologist and patients for clarity, accessibility and accuracy.

All agreed that students showed greater fluency and confidence when explaining infection after working through the Green Explorer. One student reflected, “After doing the … interactive learning, I definitely felt like I was more confident explaining […] the whole infectious process”, while another explained, “the stepwise approach with the same storyline, that was quite helpful”. The students conveyed a better understanding of the sequence of events and used the language and metaphor of the story, with the consultant noting “I can see the science and story info merging”. This addition was valued by the patients, one of whom reflected “if the doctor is sharing it with me like that, I’d be able to pass it on”. Though the consultant and patients were not informed which explanations were given after the Green Explorer, they could tell due to the adoption of language from the story.

Presenting the Green Explorer in relation to patient-based scenarios appeared to aid students in understanding the clinical relevance and value of learning through story, evident in the following quote: “I liked the pictures […] it helped me when explaining to a patient […] you just have to kind of say what you’ve seen”. This was a critical lesson for us when developing the GermBugs for implementation this year.

Year three – Implementation

The GermBugs resource is available online for students across the UK to supplement their learning. This resource features the case-based scenario previously described, allowing other students to compare GermBugs to traditional resources. In total, 10 GermBug stories including Badu the Bacteroides and Harry the Haemophilus (as shown in the pictures) have been created which educate on bacterial pathogens, the transmission of infection, diagnosis and treatment approaches.

The GermBugs resource is being introduced to second-year medical students in a tutorial this semester and they will be encouraged to use it beyond the tutorial to enhance and reinforce learning. We have, as advised, assigned formal learning objectives related to the resource and added questions to the end of year exam to achieve curriculum alignment and further convey the GermBugs’ value. This will allow further evaluation.

Conclusion

Looking back on the story so far, we are proud to have developed a microbiology teaching resource that is engaging and informed by contributions from students and colleagues with expertise in visual and digital communication. Based on our positive experience, we recommend others engage in collaborative processes when developing microbiology resources and hope we have inspired you to undertake similar co-design work. We look forward to sharing further findings from the implementation phrase – stay tuned!

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge members of the GermBug collaboration in developing the GermBugs resource: Sue Bickerdike and Charlotte Holmes: Learning technologists; Imogen Fancourt: Artist; Priyanka Gandhi, Muhammad Noor and Lucy Pangbourne: Medical students.

Andrew Kirby

Associate Clinical Professor in Microbiology, Leeds Institute of Medical Research, The University of Leeds, Old Medical School, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds LS1 3EX, UK

Jane Freeman

Associate Professor in Clinical Microbiology, Old Medical School, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds LS1 3EX, UK

[email protected]

@drjanefreeman

@hcaileeds

Alison Ledger

Associate Professor (Clinical Education Scholarship), Worsley Building, University of Leeds, Woodhouse, Leeds LS2 9NL, UK

Drs Kirby, Freeman and Ledger are based at the University of Leeds and are involved in medical student education. They have co-led the development of the GermBugs resource by contributing their clinical, educational and scientific expertise to the project.

Why does microbiology matter?

Andrew: Microbiology matters because effective control of microbial pathogens keeps us safe from serious infections, and lets us all develop our potential.

What do you love most about your job?

Andrew: Academic microbiology gives the opportunity to develop projects over the long term. A longer-term approach gives the time to work with colleagues and create impactful interventions, be them clinical or educational.

Image: Imogen Fancourt.