Diagnosing and sequencing Ebola in Sierra Leone

Issue: Future Tech

09 August 2016 article

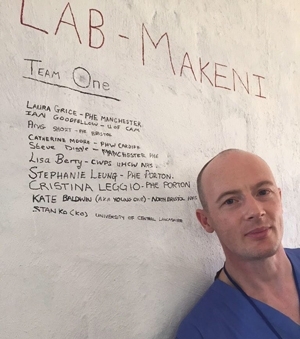

In November 2014, I was deployed with Public Health England (PHE) to establish one of the first diagnostic laboratories in Sierra Leone. Our team of 10 scientists was composed primarily of biomedical or clinical scientists from various UK hospitals or diagnostic laboratories. We were sent to Makeni, to work in an Ebola treatment centre (ETC) operated by International Medical Corps (IMC).

When we arrived the ETC was still under construction so the first weeks were spent moving boxes and equipment around a bustling building site. The early days were rather chaotic, logistics were unpredictable so the establishment of the laboratory required a lot of creative approaches including the repurposing of household items purchased from the local market for use in the laboratory.

The diagnostic lab opened on 13 December 2014 and this significantly reduced the time taken between samples being collected to the results being available from days to as short as four hours.

L–R: KATE BALDWIN, NORTH BRISTOL NHS; LISA BERRY, UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS COVENTRY AND WARWICKSHIRE (WHCW) NHS TRUST; CATHERINE MOORE, PHW CARDIFF; STEVE DIGGLE, PHE MANCHESTER; STAN KO, UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE; STEPHANIE LEUNG, PHE PORTON; CRISTINA LEGGIO, PHE PORTON; ANGELA SHORT, PHE BRISTOL; LAURA GRICE, PHE MANCHESTER; IAN GOODFELLOW, UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE.

During my first deployment to Sierra Leone, and in discussions with Dr Tim Brookes (PHE) and Professor Jeremy Farrar (Wellcome Trust), we had identified an urgent need to be able to sequence viruses in real-time. The ability to sequence patient samples within a 24–48 h time period would make the data of use for epidemiological tracing and the identification of transmission networks. By making the data freely available, it would also enable scientists to gain a better insight into how the virus was evolving in real-time rather than being reliant on the release of data following publication, which often occurred many months after samples had been isolated. The ability to sequence viruses in Sierra Leone rapidly has been critical in the recent emergence of new cases from persistently infected survivors.

I returned home on 23 December 2015 and what followed was a frantic period of contacting suppliers, obtaining quotations and putting together a grant to perform next-generation sequencing in a tent next to the diagnostic lab. In April 2015, my third deployment to Sierra Leone, I returned to Makeni to install an Ion Torrent sequencer in the ETC using support from the Wellcome Trust. Dr Armando Arias, a postdoctoral fellow in my lab, and I set off to install all the equipment and establish the sequencing workflow. Neither of us had operated a sequencer before but we had 5 days of training beforehand to enable us to install, run and, if necessary, repair the equipment. The sequencer and the other equipment arrived on 13 April 2015 and within a period of 3 days we were sending our first Ebola virus sequences back to our collaborators at the Wellcome Sanger Centre and University of Edinburgh for analysis. We have since sequenced >1,200 samples, providing >600 viral genomes, ~1/3 of all the viral sequences from the outbreak. By sharing our data with other scientists, including a team run by Dr Nick Loman, also a Microbiology Society member who was performing real-time sequencing in Guinea, we were able to provide invaluable information on the movement of cases across the borders in real-time.

In September 2015, we subsequently relocated to the University of Makeni (UniMak) and established the UniMak Infectious Disease Research Laboratory to provide both local and international scientists with access to in-country sequencing technology. The laboratory has provided support to a number of ongoing clinical trials and is providing longer-term capacity building of scientists in state-of-the-art research methods. The sequencing facility continues to provide essential support to the outbreak, including the sequencing of the last cases in Sierra Leone and the new cases from Guinea.

I would encourage all members of the Society to get involved in work in low- and middle-income countries, as it has provided me with an invaluable insight into the impact of infectious diseases on vulnerable populations. Although challenging, the six months I spent in Sierra Leone working as part of the response was without a doubt one of the most rewarding experiences of my scientific career.

I have just recently returned from a two-week trip to Makeni to run microbiology practicals for the undergraduate students at the local university (UniMak) and to begin a public engagement project in collaboration with EducAid, a UK-based charity involved in education in Sierra Leone. The Wellcome Trust-funded engagement project aims to improve the awareness of infectious diseases in secondary school students within Sierra Leone and will run until September 2017.

IAN GOODFELLOW

University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 2QQ

[email protected]

Image: 1. Makeni Team #1 preparing to establish the diagnostic laboratory at the Mateneh Ebola treatment centre run by International Medical Corps. 2. Professor Ian Goodfellow in the Public Health England diagnostic laboratory in Makeni, Sierra Leone. 3. Professor Ian Goodfellow and Sunday Kilara (International Medical Corps) preparing to unpack the equipment required to establish the Ebola virus sequencing facility. 4. Makeni Team #1 within the PHE diagnostic laboratory. The team were sent to establish the diagnostic laboratory at the Mateneh Ebola treatment centre in Makeni. All I. Goodfellow..