How do epidemics become endemic? Lessons from shigellosis in men who have sex with men

Issue: Halting Epidemics

07 February 2017 article

Understanding how epidemics become endemic is key to understanding how disease transitions and persists in populations.

I’ll begin with some definitions. The words ‘epidemic’ and ‘endemic’ are epidemiological terms used to refer to levels of a disease, but both terms are specific for a particular host in a specified area/environment. An epidemic is an increase in disease levels above normal or ‘background’ levels, but because of the specifity of area, multiple cases of malaria would constitute an epidemic in the South of England, but the same number of cases would not be considered an epidemic in Malawi, where malaria is more common. In fact, malaria is endemic in Malawi, which means that there is continued transmission of the disease in the human population without further external input. The fundamental requirements for epidemic and endemic transmission are similar, and very simply defined. For propagated epidemics (i.e. those contagiously transmitted and not related to a single point-source, such as a contaminated well), diseased individuals must infect (on average) more than one other susceptible individual in the population (this is called the basic reproduction number, or R0). For endemic transmission to ensue, R0 must remain greater than one despite any factors that make it less likely for diseased individuals to spread the pathogen to susceptible individuals (e.g. consequential immunity in the population, a small population size, or effective treatment and/or quarantine of diseased individuals).

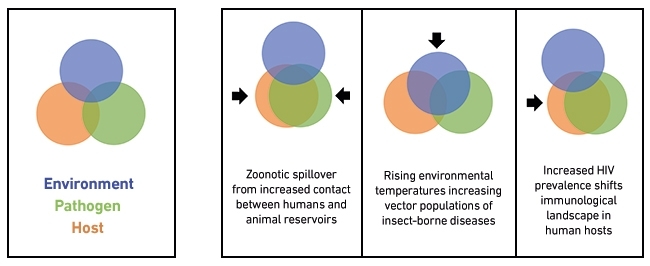

To conceptualise how changes in disease levels occur, it is helpful to think of the background level of disease resulting from a balance between the pathogen, host and environment. Simple changes in any one of these factors can precipitate disease emergence (epidemics) (Fig. 1). For example, changes in environmental temperatures can increase disease levels by altering the geographic distribution of vector populations for insect-borne pathogens such as Zika virus; an increase in host population HIV prevalence can alter the immunological landscape of host populations such that the emergence of multiple diseases might occur; and pathogen adaptation can also facilitate emergence, such as the acquisition of vitamin B5 synthesis machinery by the diarrhoeal pathogen Campylobacter jejuni aiding mammalian host infection. Although some simple shifts can result in epidemic emergence followed by endemic disease transmission, it is more common that subsequent endemic disease results from multiple changes in the balance among the three factors (host, pathogen and environment) in a complex interplay that evolves over the course of the initial emergence (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Shifts in the interactions among a host and pathogen in an environment can give rise to epidemics.

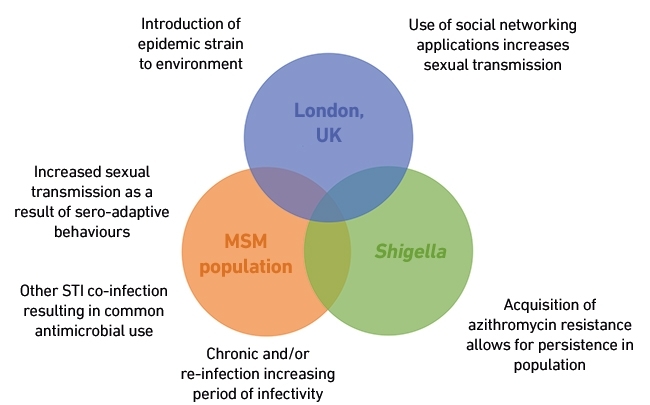

To illustrate this fully, I will elaborate on a recent example of disease that has gone from being epidemic to endemic: shigellosis in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. As background, shigellosis is a bacterial diarrhoeal disease common in low-income nations that has also been reported as a sexually-transmissible illness in MSM since 1974. Following that initial report, small-scale and apparently self-limiting epidemics of MSM-associated shigellosis have been reported sporadically in large cities around the globe and, within MSM, direct oro-anal contact and HIV infection are significant risk factors for infection. In the UK, epidemic levels of the diarrhoeal pathogen Shigella flexneri 3a associated with MSM were detected in 2009 and since then, the disease has transmitted endemically and intensified, with the emergence of two other types of Shigella: S. flexneri 2a and Shigella sonnei. Combining in-depth epidemiological information, including interview data from patients, and whole genome sequence analysis of S. flexneri 3a isolates from the outbreak and around the world provided insight on how shigellosis became endemic in this scenario (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Contributing factors that facilitated the emergence of endemically-transmitting shigellosis in the MSM population in the UK.

The first step in the emergence of shigellosis in the UK MSM population was the introduction of a novel Shigella strain to a transmission-facilitating environment. Phylogeographic analysis showed that the epidemic strain may have originated in Latin America and, within the UK, was largely restricted to London. This suggests that the sheer size of the London MSM network may have contributed to perpetuation of the epidemic, providing sufficient susceptible individuals to overcome any critical community size requirement for ongoing transmission, which is congruous with other reports of sexually-transmitted shigellosis epidemics arising in major population centres. In addition to its large size, the density of the transmission network may have also contributed. Interview data from shigellosis-affected patients revealed high numbers of sexual partners, often without the use of condoms and the frequent use of social networking applications, such as Grindr (released in 2009), to facilitate meeting partners for sexual contact. The recent coincident emergences of multiple other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including gonorrhoea, chlamydial disease and syphilis, supports the notion that the suitability of the transmission network contributed to the emergence of shigellosis in the UK MSM population.

In addition to environmental factors, there were also host-specific factors that aided the endemic transmission of shigellosis among MSM in the UK. Patient interview data revealed common co-infection with HIV and sero-adaptive behaviours, including HIV-positive men actively seeking HIV-positive partners for condomless sex. Sero-adaptive behaviours have been increasing since the advent of Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy (HAART), and consequential increased sexual contact among HIV-positive individuals may have led to a generalised increase in STI transmission, including shigellosis. This is supported by the co- or recent-infection with other epidemic STIs (i.e. gonorrhoea, chlamydial disease and syphilis) of HIV-positive shigellosis patients. In addition to this transmission-moderating effect of HIV therapy, the impact of HIV infection itself on the course of shigellosis infection is unclear. There are some reports of chronic Shigella infection in HIV-positive individuals, and this, along with the potential for rapid reinfection, was supported by the recent genomic epidemiology study. Thus, increased transmission among HIV-positive hosts with the potential for chronic and/or re-infection (which would increase the duration of infectivity) further enhanced Shigella transmission.

The final contributing factor identified in the emergence of endemic shigellosis in the UK MSM population was pathogen adaptation. Whole genome sequence analysis of the MSM-associated strain of S. flexneri 3a revealed that lineages occurring later in the outbreak were resistant to the antibiotic azithromycin. Although the recommended antibiotic treatment for shigellosis is ciprofloxacin, the other STIs commonly reported in these patients (i.e. gonorrhoea, chlamydial disease, and syphilis) are often treated with azithromycin. The extent of antibiotic use in shigellosis-affected MSM was revealed in a German study, where 43% of patients had received antimicrobials in the six months prior to diagnosis. This creates a sustained selective pressure for Shigella circulating in the community to acquire azithromycin resistance, particularly given that chronic infection might overlap with treatment periods for comorbid STIs.

To summarise then, the emergence of MSM-associated Shigella in the UK is explained partly by the mere introduction of a new pathogen to a suitable environment and host population. That is, a technologically-enhanced, large, dense transmission network of potentially immunocompromised individuals in which shigellosis is one of multiple increasing STIs. However, unlike previously described shigellosis epidemics in MSM, this emergence was followed by sustained endemic transmission, which suggests that in addition to these host and environmental factors, pathogen adaptation played a key role. This example demonstrates how complex the factors can be that facilitate the transition of a disease from being epidemic to endemic, and the utility of monitoring for pathogen adaptation over the course of disease outbreaks.

Kate Baker

Institute for Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB

[email protected]

Further reading

Aragon, T. J. & others (2007). Case-control study of shigellosis in San Francisco: the role of sexual transmission and HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 44(3), 327–334.

Baker, K. S. & others (2015). Intercontinental dissemination of azithromycin-resistant shigellosis through sexual transmission: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 15(8), 913–921.

Borg, M. L. & others (2012). Ongoing outbreak of Shigella flexneri serotype 3a in men who have sex with men in England and Wales, data from 2009–2011. Euro Surveill 17(13):pii=20137.

Gilbart, V. L. & others (2015). Sex, drugs and smart phone applications: findings from semistructured interviews with men who have sex with men diagnosed with Shigella flexneri 3a in England and Wales. Sex Transm Infect 91(8), 598–602.

Hoffmann, C. & others (2013). High rates of quinolone-resistant strains of Shigella sonnei in HIV-infected MSM. Infection 41(5), 999–1003.

Simms, I. & others (2015). Intensified shigellosis epidemic associated with sexual transmission in men who have sex with men – Shigella flexneri and S. sonnei in England, 2004 to end of February 2015. Euro Surveill 20(15):pii=21097.

Image: Images: Shigella flexneri invading embryonic stem cell. David Goulding, Sanger Institute, Wellcome Images. Figs. 1 and 2. K. Baker..