HIV in pregnancy

Issue: HIV and AIDS

06 November 2018 article

The long-term outlook for people living with HIV has been revolutionised by early and lifelong use of combination antiretroviral treatment (cART). Effectively treated individuals with plasma HIV RNA <50 copies ml–1 (‘undetectable’) can have a normal life expectancy.

In 2015 in the UK, 88,769 people were seen for HIV care, 25,564 of whom were women, half of whom were of child-bearing age. The passing of HIV from a woman to her foetus is called vertical transmission and is largely preventable. Vertical transmission will most often occur in the perinatal period. With no intervention, the vertical transmission of HIV can be as high as 25–30%. The incidence of vertical transmission of HIV in the UK is at its lowest ever at 0.27% for all women with HIV and even lower at 0.14% for women with HIV on effective cART.

This is because of the following interventions:

1. Antenatal HIV testing to diagnose pregnant women living with HIV.

2. Effective cART for the woman.

3. Management of labour.

4. Avoidance of breastfeeding.

5. Post-exposure prophylaxis for the baby.

Antenatal HIV testing

Routine opt-out antenatal HIV testing in the first trimester was introduced in 2000 in the UK, following a successful pilot programme. The number of pregnant women testing for HIV during pregnancy is very high at >90%. As a result, the number of women presenting with HIV for the first time in pregnancy or in labour has fallen dramatically. Since 2015, 89% of pregnancies in HIV have been in women diagnosed preconception. This is important because the highest risk of transmission is in women undiagnosed at delivery.

It is also important to note that even women presenting in labour with untreated HIV can have many of the interventions below to reduce vertical transmission. Therefore, any woman in labour without a documented HIV test should be urgently tested.

Effective cART for the woman

Maternal HIV viral load (VL) is the most important determinant of vertical transmission of HIV. The first published data on the effective use of antiretroviral therapy to prevent vertical transmission of HIV appeared in 1994. It showed that pregnant women treated with zidovudine monotherapy, which was standard treatment at the time, versus women not on any treatment, had a 67% reduction in vertical transmission. Since then, HIV treatment has advanced. cART consisting usually of three antiretroviral agents (ARVs) is standard care and should be started on diagnosis of HIV regardless of CD4 count, a marker of immune function. Therefore, a woman living with HIV may conceive while already on cART or may be started on cART if diagnosed in pregnancy. Pregnant women with HIV remain a special group with specific guidelines for HIV treatment based on teratogenicity and toxicity data on cART use in pregnancy from published data, national HIV in pregnancy databases and international databases such as the antiviral pregnancy registry. For example, earlier ARVs stavudine and didanosine caused very significant toxicity to both woman and baby and are no longer used either in pregnancy or in non-pregnant adults.

When starting treatment, as with any medication, the first trimester is avoided if possible, but started by 24 weeks gestation with the aim of getting HIV VL to undetectable by 36 weeks. Since 2015, 80% of women living with HIV in the UK have conceived on cART. The most common toxicity with cART is preterm delivery and this is particular to a class of ARVs called protease inhibitors. Pregnant women with HIV are monitored more frequently than non-pregnant adults. Women on cART without adequate safety data in pregnancy may be switched to agents with which we have more experience, such as efavirenz and boosted ataznavir, but should see their HIV physicians when they become pregnant to discuss this. All women should take folic acid preconception and for the first 14 weeks of pregnancy.

Management of labour

A woman living with HIV on effective cART can have a normal vaginal delivery if there is no obstetric reason not to. Labour should be managed in the standard way. Forceps or vonteuse may be used, and foetal scalp monitoring or blood sampling can be performed if clinically indicated in this group. Early pre-cART evidence suggested that rupture of membranes (ROM) greater than four hours caused a highly significant increase in risk of vertical transmission. Current evidence suggests that duration of ROM up to 24 hours is safe but only in women with HIV RNA <50 copies ml–1. Elective caesarean section (C-section) as late as possible and after 39 weeks is recommended in women with an HIV RNA >400 copies ml–1 even if she is on cART to minimise vertical HIV transmission.

Rates of vaginal delivery in the UK, including trial of normal delivery after a previous C-section, are increasing (40%). In 2016, an elective C-section was performed only in 10% of women living with HIV, down from 70% in 2000. Unfortunately, emergency C-section rates remain high but may be explained in part by lack of data on duration of ROM >24 hours and failure of vaginal delivery after a previous C-section.

Avoidance of breastfeeding

The risk of HIV transmission from breast milk was first identified in 1992, with the risk from breastfeeding reported as 15–25%. Even now with women on effective cART, whether or not to breastfeed remains controversial. There is no randomised controlled data in a UK-type setting assessing risk from breastfeeding when a woman is on cART. There are data from developing countries to suggest the risk is probably very low, at 0.1–5%. However, there are a number of issues to consider. The only certainty we have is that avoidance of breastfeeding will have zero transmission risk to the infant. A woman may be supported to breastfeed her baby, if her HIV VL is undetectable on cART and remains this way each month she is seen with her baby. Her HIV transmission risk may change if she develops mastitis or gastroenteritis or if her baby becomes unwell with vomiting and diarrhoea. Therefore, multidisciplinary input and support at this time is hugely important for both mother and baby.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for the baby

All babies born to women living with HIV will receive PEP. What they receive and for how long depends on how the woman’s HIV is controlled. For a woman on effective cART, the baby will only need 14 days of zidovudine monotherapy. But for a woman presenting late, in labour or with a detectable HIV RNA, her baby may need longer treatment and/or the addition of more ARVs to prevent HIV. The baby will be tested at birth and twice more after finishing PEP, usually by three months. Although there is still a final test at 18 months the HIV status of the baby can usually be confirmed by the first three tests.

In summary, women living with HIV and receiving good care and effective cART are very likely to have a HIV-negative baby. The multidisciplinary team of HIV, Obstetrics and Paediatrics work together with peer mentors to support mother and baby through this journey, but with evidence-based interventions the outlook is extremely good for both.

Further reading

BHIVA HIV Guidelines in pregnancy 2018 www.bhiva.org/PrEP-guidelines. Last accessed 23 October 2018.

The Antiviral pregnancy registry www.apregistry.com. Last accessed 23 October 2018.

The National Study for HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood www.ucl.ac.uk/nshpc. Last accessed 23 October 2018.

What we do and why – mothers2mothers www.m2m.org. Last accessed 23 October 2018.

Yvonne Gilleece

Brighton & Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust

[email protected]

Twitter: @DrYGilleece

Yvonne Gilleece is Honorary Senior Lecturer and Consultant in HIV and Sexual Health Brighton & Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, Chair of the British HIV Association HIV in Pregnancy Guidelines and Chair of SWIFT, supporting information and research for women living with HIV.

What advice would you give to someone starting out in this field?

Get involved in research from early on in your training as you will be learning and trying to improve patient outcomes for the rest of your career.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

When I see a really complex patient, whether they have medical or psychosocial problems, and knowing I was absolutely the right person for that patient to have seen.

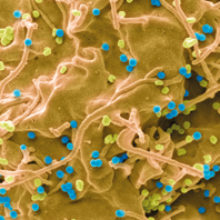

Images: Coloured scanning electron micrograph of a 293T cell infected with HIV (cyan). Magnification: x20,000 at 10 cm wide. Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library.

A pregnant woman taking a tablet containing folic acid. Ian Hooton/Science Photo Library.