Editorial

Issue: Light

11 August 2015 article

2015 is the International Year of Light and Light-based Technologies. This International Year intends to bring together groups to provide solutions to global challenges in areas such as energy, education, agriculture and health. Light is so very crucial to our existence, it is woven into the very fabric of our lives and our being. It is composed of a myriad of wavelengths, energies and colours, and as a species we have evolved to capture, split and create light.

Personally, I have a dual relationship with light. I am aware that I often take its presence for granted; it only emerges into my consciousness when it disappears and we return to darkness at night. For millennia, societies have learnt to use this relentless pattern of light and dark to mark existence and measure time. This cadence of light and dark plays a vital role in providing the inherent drivers for the circadian rhythms that underpin our daily lives. These rhythms are not restricted to humanity but pervade the microbial world. Hans E. Waldenmaier, Anderson G. Oliveira, Jennifer J. Loros, Jay C. Dunlap and Cassius V. Stevani have written an article that describes the circadian rhythm that underpins fungal bioluminescence. They illustrate how studies on the Brazilian mushroom Neonothopanus gardneri is revealing clues about ‘how’ and ‘why’ fungi produce light.

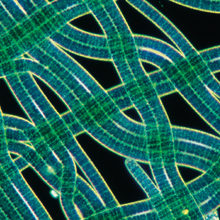

Humanity has studied, tested, understood and described how the fundamental energy of light can be captured and transformed into the basic building blocks of life. It is this elemental feature of light that was one of the reasons that I chose to study biochemistry. The biochemistry of chloroplasts has always held an enduring fascination for me and I am intrigued by the concept that chloroplasts are microbes ‘captured’ by other cells. Phoebe Tickell and Richard G. Dorrell provide an insight into this process and explain how we rely on plants and algae to make use of light energy, through the process of photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria (‘blue-green algae’) invented the main form of photosynthesis we see today, and it is used by a wide range of eukaryotes, from unicellular algae and giant seaweeds in the oceans to plants that flourish on land, and common to all these organisms are the cyanobacteria-like chloroplasts. In many ways this relationship can be considered as the ultimate symbiosis. Tim Miyashiro’s article outlines a symbiotic relationship that has facilitated our understanding of how symbioses between animals and bacteria developed and evolved. It describes how bioluminescence is emitted by populations of a marine bacterium called Vibrio fischeri housed within a dedicated structure called the ‘light organ’ of the bobtailed squid, Euprymna scolopes.

Light has revolutionised medicine, and this is pertinent to microbiology and human health. Tom Grunert discusses how we can take advantage of the infrared region of the spectrum to provide a unique fingerprint signature of intact microbial cells in order to improve and increase our ability to identify pathogens. This development reflects the fact that the metabolic state of bacteria can be determined from absorption patterns from this part of the spectrum. Michelle Maclean, John G. Anderson and Scott J. MacGregor describe how bacterial inactivation using violet-blue light has emerged as an area of interesting research. Although less biocidal than ultraviolet (UV) light, visible violet-blue light (the narrow wavelength band centred on 405 nm) has proved effective for inactivation of a range of microbial species, which is generating interest in healthcare and food facilities.

Capturing scientific images is a fundamental part of enhancing scientific knowledge and understanding. Kevin Mackenzie provides a commentary that outlines how this process has changed and developed over time, as our ability to use light to capture images reflects modern advances and new technologies.

This edition of Microbiology Today not only looks forward to the future but it provides an understanding of how historical steps in microbial evolution underpin the very essence of our modern lives.

LAURA BOWATER

Editor

[email protected]

Image: Light micrograph of a filamentous blue-green algae (Cyanophycophyta), called Oscillatoria sp. Sinclair Stammers/Science Photo Library..