Comment: Probiotics – a living story

Issue: Microbes and Food

07 August 2018 article

What do you remember about 2001, apart from 9/11? The publication of the Human Genome Project? Thinking how good Lance Armstrong was in winning his 6th Tour de France? Sitting in your car listening to the number one selling song of the year, “It Wasn’t Me,” by Shaggy?

Well, in Cordoba, Argentina, I was chairing a United Nations and World Health Organization Expert Panel that was asked to define probiotics. It wasn’t something that would have resulted in brownie points at my university, since nobody there had ever heard of ‘probiotics’. In fact, with a few exceptions, nobody in Canada had.

Fast-forward to 2018, and while some events are now assigned to history, probiotics are writing their own in profound ways.

The big question

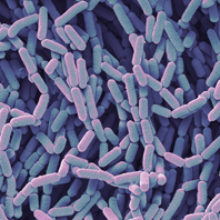

But, before we discuss the big question, ‘what is a probiotic?’, what was the outcome from Cordoba? The definition of a probiotic: ‘Live micro-organisms, that when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.’ In lay terms, it means ingesting, inserting or applying living microbes (usually bacteria) to your body (or to an animal or other living host). These microbes must first have been shown to have certain beneficial attributes, like being able to kill a diarrhoea-causing bacterium. They are placed in a delivery vehicle (for example a dairy product or capsules) with viable numbers, even at the end of shelf-life, that are sufficient to bring about a positive response. That response should be measurable, even if it does not result in you perceiving a difference.

It might be easier to state what probiotics are NOT.

- Well, they are not in you – unless you have taken them.

- They are not fermented food – unless that specific food has been documented and tested in a human study.

- They are not prebiotics – a substrate that is selectively utilised by host micro-organisms conferring a health benefit.

- They are not multiple strains selected by a marketer.

- Lactobacillus is not a probiotic, nor is Lactobacillus acidophilus. These are names, not specific strains with documented probiotic activity.

- They are definitely not dead – that sounds like a cool title for a crime thriller.

- Oh, and while we’re at it, lactobacilli is not italicised, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus does not have a capital R.

By now, you’re thinking I get hung up on semantics. But really, if you went to buy a car and the salesman didn’t know if it had three or four wheels and an engine, wouldn’t you be worried? Likewise, if he told you it was the best car on the planet, even at £1,576, you’d better find another dealership.

The question I’m asked the most

As a new immigrant to Canada in the early 80s, I was constantly asked, “where is your accent from?” That was easy to answer – my throat.

Now, it’s, “which probiotic should I take?” Easy, but split into three replies. Firstly, “it depends on why you are taking a probiotic.” Secondly, “it depends on how you prefer it, as food or dried supplement.” Thirdly, “I prefer you do the homework to know the options.” That may sound like a cop-out, but who am I, without an MD degree, to ask personal medical questions and then decide on someone’s course of action?

Fortunately, a group of experts in Canada and the USA have made it easier for me to guide people to the place where they can get reliable information on products. In Canada, it’s www.probioticchart.ca and in the USA it’s www.usprobioticguide.com, but for those of you reading this from the UK or Europe, sorry, nobody has repeated this unique evaluation of every product sold in your country. It is simple really. You match the product contents, dose and formulation with human studies published and available on PubMed, and then you determine the level of evidence of the study(ies) against the health outcome.

The result is a table that says, you may have heard of Align, but if you are trying to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI), it’s not the product for you. Then, if your fitness instructor or health food shop owner says that Ole Ole Ole is the best probiotic since snake oil, because it has 20 strains and 50 billion organisms, all you need to do is check the list. It won’t be there, so now you have to confront your trusted advisor and tell them they are misinformed. It might be the end of your relationship, or it might make them get back to the producer and recommend they perform appropriate human studies to prove their product does indeed give you the perfect figure and help you win the Tour de France at age 76. Yes, I’m being sarcastic. The longer the list of documented strains, the happier we will all be.

Probiotics are impacting life

I hope you get to visit The Loch Ness Monster Centre and Exhibition near Inverness. You enter as a cynical non-believer and exit heading straight for the loch to look for bumps hovering across the water. Okay, so it’s not a great analogy, but my point is if you really look at the data, there’s lots to believe about probiotics.

The evidence for preventing necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) led to our hospital instituting probiotics as standard therapy for premature, low birth weight newborns, and while the rate of NEC was not overly high at around 3% beforehand, it’s almost zero now. The ultimate in clinical translation.

But probiotics are not a silver bullet. They may never reduce cholesterol as much as statins, but they won’t cause muscle wasting and terrible side effects. They reduce colic in breast-fed babies, reduce the duration of diarrhoea and respiratory infections and recurrence of UTI. What else can enhance immunity, reduce side effects of HIV/AIDS and many other drugs, reduce stunting and improve maternal and infant health?

In the late eighties I had a grant rejected on probiotics to prevent UTI with a reviewer stating, “why are you doing this when we have antibiotics?” While we now suffer the penalties of excessive antibiotic use, my only satisfaction from rejection is seeing many of these grant panellists now studying probiotics. We must be doing something right.

Translation means to all people, not just the rich

Of the thousands of grants I have read, almost all start with stating a clinical problem their project relates to then many describe so-called ‘mechanistic’ experiments in mice. I suspect less than 10% of these projects ever make the slightest dent in that disease. If we truly want to understand health and prevent and treat disease, we need to direct funding to studying and replenishing beneficial microbes in humans.

Since 2004, I have been committed to giving people in Africa access to probiotics. With amazing colleagues, we are now providing the opportunity for everyday citizens in villages and towns in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda to produce probiotic fermented food (www.yoba4life.org, www.westernheadseast.ca).

These efforts are reaching over 250,000 people, while in Argentina, a wonderful school programme is doing the same through a locally discovered probiotic yogurt.

Imagine the possibilities!

It’s a microbial world, and probiotics have an important place in it. Imagine what we could do as a collective?

Gregor Reid

University of Western Ontario, Lawson Health Research Institute, Rm F3-106, 268 Grosvenor Street, London, Ontario N6A 4V2, Canada

[email protected]

Gregor Reid is Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Surgery at The University of Western Ontario. He has published 520 peer-reviewed papers, been awarded 28 patents and given over 600 talks in 54 countries. He has many awards, including an Honorary Doctorate from Orebro University in Sweden, and being appointed to the Royal Society of Canada and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences.

What is the most enjoyable bit of your job?

The highs. They come in many forms (discoveries, papers accepted, grants won, awards, student successes, invitations to speak, people personally benefiting from probiotics, etc.), and you need them to offset the lows which are sadly inevitable in science.

What advice would you give to someone starting out in this field?

Find something to believe in that is real, and make it part of your life. The concept of lactobacilli being beneficial for the female urogenital tract made sense from day one, and made even more sense the more I studied it. I was relentless in its pursuit, making the data be the marker, not mythical ideas. Passion is critical if what you are passionate about has a foundation in stone, not sand.

Images: The thumbnail is Lactobacillus rhamnosus bacteria, coloured scanning electron micrograph (SEM). Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library.

Image 2: ayo888/Thinkstock.

Image 3: Children eating probiotic yogurt in Mwanza, Tanzania. Gregor Reid.