Not such a fungi – fungal disease and the end of the world as we know it?

Issue: Microbiology in Popular Culture

07 November 2017 article

The natural world can be stranger than fiction. Scientists observe things that are astounding and amazing but also disconcerting and sometimes horrifying, and all of which can inspire and be appropriated into popular culture.

A sign of things to come?

The entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis is infamous for causing lethal fungal disease (FD) in ants. The fascinating infection caused by Ophiocordyceps has the ability to change the behaviour of the ant, so called ‘zombification’. This process forces the ant to relocate to environmental conditions that favour fungal proliferation. The ant fixes itself to the underside of a leaf using its mandibles, where it remains until death. This is followed by the production of a fruiting body that protrudes out of the ant’s head and ruptures to release hundreds/thousands of spores capable of infecting other ants in the vicinity, even destroying entire colonies.

This process of infection has been exploited in the sci-fi horror genre, where cerebral infection in humans by O. unilateralis was the cause of the ‘zombie apocalypse’. In the popular 2013 video game The Last of Us, and more recently the 2016 film The Girl with all the Gifts (based on the 2014 book of the same name), the fungus was deemed responsible for an infectious disease spread by transfer of bodily fluid or fungal exposure. Through infection of the brain, humans were transformed into cannibalistic beings that unknowingly spread the infection through primal instincts, ending society as we know it. In both, the only hope for a cure lay with two children, who either showed immunity to infection or were born to an infected mother and bore cannibalistic traits while retaining human intellect. While it is accepted that O. unilateralis infection does alter behaviour in ants, it is far from making them cannibals and simply represents the fungi ensuring its further propagation. Nevertheless, it does bring FD to the fore, and for a manifestation that is often considered of low incidence or mainly superficial in presentation, this can only be a good thing.

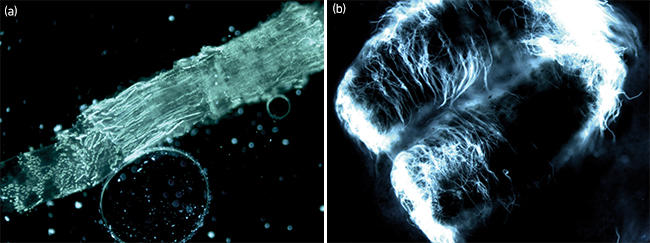

Fig. 1. Dermatophyte infection of a hair follicle, showing (a) internal hyphae and spores (endothrix), and (b) external fungal hyphae (ectothrix).

Scratch below the surface

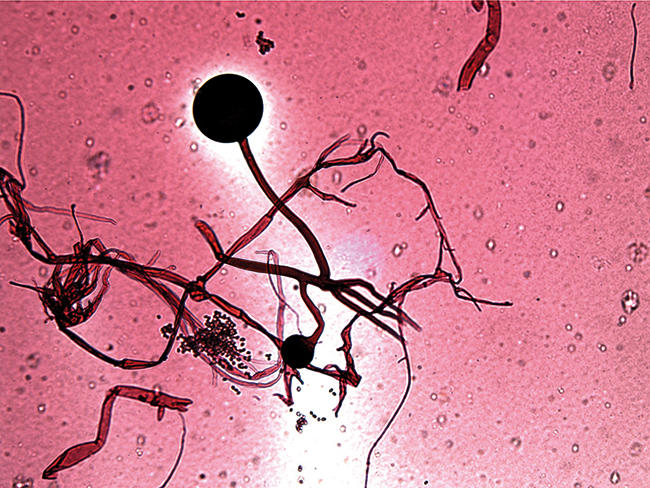

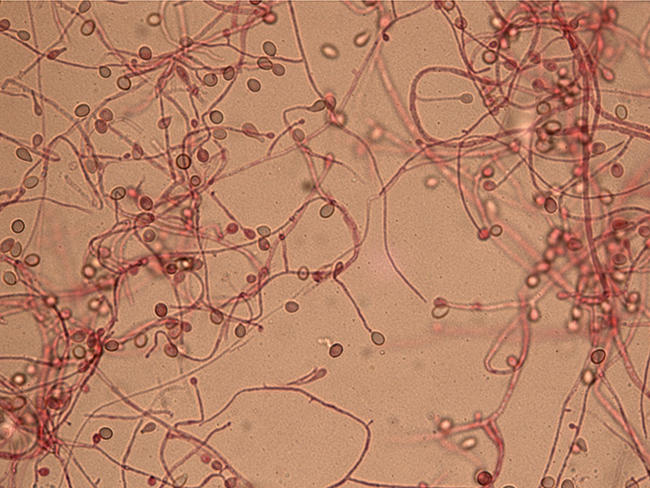

FD is far more than hair/nail infections (Fig. 1), ringworm or candidal thrush – medical conditions often encountered by the general public and representing a significant burden that is almost impossible to determine but often associated with social stigma. An ever-increasing population of immuno-suppressed patients (e.g. haematological malignancy, HIV infection, solid organ transplantation and genetic conditions) are surviving longer periods of severe immuno-suppression, increasing the opportunity for invasive FD, and patients with underlying respiratory conditions (e.g. cystic fibrosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder) are increasingly diagnosed with allergic or chronic forms of fungal infection requiring long-term treatment. A major marker of the 1980s HIV epidemic was the increased incidence of Pneumocystis pneumonia and cryptococcal meningitis. Traumatic implantation of fungi have resulted in FD in soldiers post-exposure to improvised explosive devices in Afghanistan and Iraq, and in civilians engulfed by large scale natural disasters such as the 2011 EF-5 rated tornado that devastated Joplin, Missouri. In both situations tissue was penetrated with shrapnel contaminated with soil/detritus containing environmental fungi (Mucorales species, Fig. 2) that became opportunistic pathogens. Insertion into the tissue resulted in complicated FD in severely traumatised, but immuno-competent patients. Cases of FD can also occur in immuno-competent patients after a simple garden injury, such as severe prick with a thorn. If the fungus involved is broadly resistant to antifungal therapy (e.g. Scedosporium species, Fig. 3) then management can be dependent on extensive surgical debridement. Unfortunately, large-scale outbreaks of FD have also been associated with the healthcare setting. In 2012/13, a US multistate outbreak of fungal meningitis was caused by the use of methylprednisolone acetate drugs contaminated with fungi at a New England compounding centre. Epidural injection of this contaminated steroid resulted in 751 cases of meningitis and 64 deaths. Fungal keratitis associated with the inability of contact lens disinfectant to inactivate fungi, including resistant species such as Fusarium, remains a global concern.

As our ability to manage critically ill and severely immuno-compromised patients improves, the opportunity for FD increases and it is almost inevitable that the incidence will increase.

Fig. 2. Microscopic image of a Mucorales species.

Fig 3. Microscopic appearance of a Scedosporium species.

The current state of play

It is estimated that globally almost 15 million individuals will be infected with allergic, chronic or invasive FD, and of these approximately 2 million will die. More people die from FD than malaria and tuberculosis; while the latter two are accepted as global clinical concerns FD is somewhat ignored. Lack of access to state-of-the-art diagnostics and therapy hamper care in low-income countries, and it is proposed that 80% of cases could be saved if the best tests and treatment were available.

The 2016 UK Government review into antimicrobial resistance touched on antifungal resistance, describing the overuse of antifungals in agriculture. It emphasised the need for regulation, but in agriculture this will always be countered by the need to produce food crops. It highlights the ethical dilemma of restricting antifungal use to protect the limited number of clinical antifungal drug classes currently available, against the ever-growing need to produce more and more food for the expanding population. Paradoxically, an issue which would be propagated further should more individuals be successfully treated for FD.

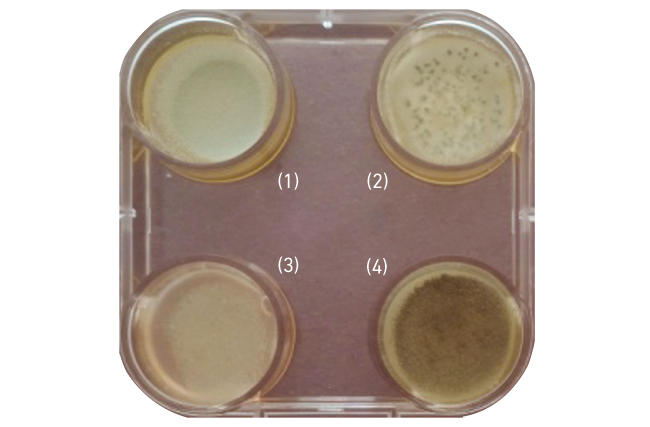

Ominously, fungi have the ability to reproduce asexually, whether through budding in yeasts or spore production in filamentous fungi, the offspring will be exact clones of the parent. If resistant mechanisms are apparent these will be passed on, in the case of filamentous fungi, to potentially millions of spores that can travel hundreds to thousands of miles on air currents. Being environmental organisms fungi do not require a host, and if agricultural antifungal use continues natural selection will favour resistant fungi in antifungal-treated areas. The most ubiquitous fungus with airborne spores, Aspergillus fumigatus, is already showing significant increases in resistance to azole therapy due to agricultural use (Fig. 4). Hundreds of spores from this organism are inhaled by humans on a daily basis, and globally over 10 million people are estimated to suffer from one form of the clinical manifestations. Mortality rates of invasive aspergillosis are already high (≥40%), but delayed appropriate therapy will increase this significantly!

Fig. 4. Aspergillus fumigatus isolate 302w1, demonstrating resistance to azole antifungal therapy: (1) itraconazole, (2) voriconazole, (3) posaconazole and (4) no antifungal control.

Not to be outdone the yeasts are also cashing in, with the recent emergence of Candida auris, which is almost inherently resistant to fluconazole, and rapidly develops resistance to other classes of antifungal therapy. Amazingly, different yet resistant, strains of this organism have emerged across the globe and it is not yet clear what activated their appearance. It has been associated with several outbreaks in healthcare settings and is readily resistant to disinfectant treatments, and colonisation of patients is difficult to eradicate, even in those successfully treated for infection.

In conclusion

It is unlikely that the sci-fi depiction of fungi in converting humans into mindless zombies will occur. It is true that FD can alter/control the behaviour of insects, but this is less concerning than the emergence of antifungal resistance in the main fungal pathogens, Aspergillus and Candida. It is well known that the only cure for zombification is to sever the central nervous system, usually by decapitation; this would not fit well in our current clinical algorithms for managing FD! However, we must avoid a situation where we are only able to offer palliative care due to the lack of therapeutic options or a delayed diagnosis of resistant FD.

An eminent mycologist has proposed that fungi played a role in the extinction of the dinosaurs, and we must prevent this happening to us. Remember, every single mushroom is edible, at least once!

P. Lewis White

UKCMN Regional Mycology Reference Laboratory, PHW Microbiology Cardiff, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4XW

[email protected]

Further reading

Abbas, K. M. & others (2016). Clinical response, outbreak investigation, and epidemiology of the fungal meningitis epidemic in the United States: systematic review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 10(1), 145–151.

Casadevall, A. (2005). Fungal virulence, vertebrate endothermy, and dinosaur extinction: is there a connection? Fungal Genet Biol 42(2), 98–106.

Jugessur, J. & Denning, D. W. on behalf of the Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections (GAFFI) (2016). Hidden Crisis: How 150 people die every hour from fungal infection while the world turns a blind eye. Accessed 31 August 2017.

O’Neill, J. (2016). The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Accessed 31 August 2017.

Images: Figs. 1 to 4. P. Lewis White.