Syphilis - the great scourge

Issue: Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

21 May 2013 article

The Turks called it ‘the disease of the Christians’ while the Persians called it ‘the disease of the Turks’. It has variously been attributed to the French, the British, the Polish, the Germans and the Portuguese. But what cannot be denied is that syphilis has been a scourge of mankind for over 500 years at least – and unfortunately continues to be so.

SIR RICHARD EVANS

On 5 July 1495, a doctor accompanying Venetian troops as they pushed forward to expel an invading French army from Italy came across a new and disturbing sight among the captured soldiers of the French king. The doctor encountered ‘several men-at-arms or foot soldiers who, owing to the ferment of the humours, had pustules on their faces and all over their bodies. These looked rather like grains of millet and often appeared on the outer surface of the foreskin. Some days later, the sufferers were driven to distraction by the pains they experienced in their arms, legs and feet, and by an eruption of large pustules, which could last for a year or more if left untreated’.

Another Venetian doctor reported seeing sufferers who lost their eyes, hands, nose or feet, with sores penetrating to the bones. ‘Through sexual contact’, he wrote, ‘an ailment, which is new, or at least unknown to previous doctors, the French sickness, has worked its way to this spot as I write’.

Most of King Charles’s troops were mercenaries, not only from France but also from Flanders, Switzerland, Germany, Italy and Spain. As the defeated French troops were disbanded, they returned home, carrying the new disease with them. Within a couple of years, the ‘French sickness’ had spread across Germany and by the early years of the new century the ‘German sickness’ had broken out in Poland and then the ‘Polish sickness’ in Russia. The Turks called it ‘the disease of the Christians’ while the Persians called it ‘the disease of the Turks’. Before long, the disease was being spread by the crew of Vasco da Gama’s ships to the people of India and Japan, where its origins were reflected in the name ‘the Portuguese sickness’, while ‘the British sickness’ eventually spread to Tahiti and the Pacific in the course of the 18th century. By 1553, the disease was widely known as syphilis, the root of the word coming from an epic Latin poem, Syphilis sive morbus gallicus – ‘Syphilis or The French Disease’, published in 1550 by Girolamo Frascatoro, a medical student of Copernicus.

Where did this devastating new disease originally come from? Almost everyone who commented on the disease from 1494 onwards regarded it as something entirely new in Europe. This was the very year in which Christopher Columbus returned from his first expedition to America. The Portuguese doctor Rodrigo Diaz da Isla reported that he had treated a number of Columbus’s crew for the disease when they landed in Barcelona. No doubt, patrons of the brothels of Barcelona were quickly infected with the disease brought by the returning sailors and from there, the disease spread to Italy with the troops.

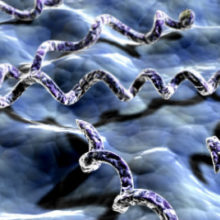

Some modern archaeologists have cast doubt on this view, suggesting that traces of the disease were found in the bones of Europeans buried long before Columbus’s expedition. However, a systematic investigation of all 54 cases featured in published reports concluded, in December 2011, that none of this skeletal evidence was reliable in terms of diagnosis or dating when subjected to standardised analyses. The bacterium Treponema pallidum, which causes syphilis and, in various sub-forms, other related diseases, such as yaws, was genetically sequenced as long ago as 1998. This has helped further research into when exactly the disease arrived in Europe. As yet, no evidence has been found dating it to human remains before 1494.

By the mid-16th century, observers were beginning to note that the disease was declining sharply in virulence. Either people had developed some resistance to the most extreme symptoms or the disease itself had mutated. Whatever the reason, it settled into the form, or forms, it takes to the present day. Syphilis remained a common disease in the 17th and 18th centuries. Physicians did not distinguish between syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases so it is often difficult to decide what exactly someone like Dr Johnson’s biographer James Boswell was suffering from when he reported in his diary that he had an attack of a ‘disgusting disease’ after visiting a ‘low house in one of the alleys in Edinburgh’, or Casanova when he reported that he had to undergo a 6-week course of treatment for ‘the sickness we describe as French’. The composer Robert Schumann’s madness and premature death strongly suggest that he suffered from syphilis; with Franz Schubert the connection is less certain.

It was only in the later 19th century that progress was made in identifying the different types of sexually transmitted diseases. In 1838, Philippe Ricord, a French physician, established the existence of syphilis as a distinct form of infection. In 1905, two German scientists, Fritz Schaudin and Erich Hoffmann, identified the causative agent of syphilis. Shortly afterwards, Paul Ehrlich, a German physician and scientist, developed a chemical treatment for syphilis, which he called Salvarsan. It began being used in dispensaries set up in many countries during and after the First World War, although on the whole it was less than effective and had some dangerous side effects.

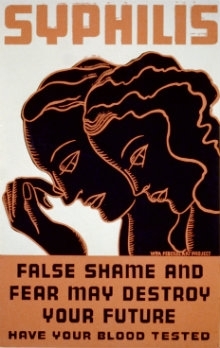

Infection rates soared as a result of the First World War. In the mid-1920s syphilis was killing 60,000 people a year in England and Wales, compared to tuberculosis, which was causing 41,000 deaths a year. An enormous propaganda effort unfolded, led by governments and a whole variety of voluntary associations, for the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. In the USA, Roosevelt’s New Deal pushed a major public health programme centred on the disease.

With the coming of the Second World War, the US government’s efforts to protect the health of its troops were redoubled. The American obsession with finding a truly effective cure led to two clinical experiments that later became infamous examples of cavalier disregard for basic principles of medical ethics. In 1942, the US Public Health Service began trials with a carefully selected population of 399 poor black sharecroppers in Alabama who had already contracted syphilis. They were told that they were being treated for ‘bad blood’ and were administered mercury, Salvarsan and bismuth in a variety of tests, all of which had unwelcome side effects. Some were given placebo treatments. The study was brought to an end in 1972 after concerned doctors alerted the press. By this time, 28 of the original 399 men had died of syphilis, 100 had died of related complications, 40 of their wives had been infected with the disease and 19 of their children had been born with the disease.

Even more shockingly, in 2010 it was revealed that the US Public Health Service, with the co-operation of the Guatemalan Government, had deliberately infected around 1,500 soldiers, prostitutes, prisoners and mental hospital inmates in Guatemala with syphilis and other diseases between 1946 and 1948 in an attempt to gauge the efficacy of treatment with antibiotics. The courses of treatment were broken off prematurely when the penicillin ran out, leaving many of the subjects to die a painful death. The US Government has since apologised to Guatemala.

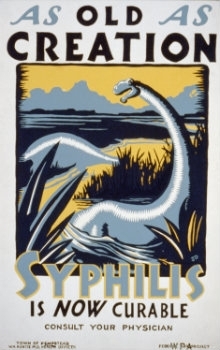

From the early 1950s, penicillin was used as a treatment and proved highly effective. Yet from the 1960s onwards, with the advent of the contraceptive pill, the incidence of the disease began to increase again. In 1999, there were 12 million cases reported worldwide. While war and conflict continue to rage in various parts of the world, syphilis, which has been associated with unrest from the very beginning, will continue to wreak havoc on humankind, despite all the efforts to prevent and eradicate it.

SIR RICHARD EVANS

Regius Professor of History and President of Wolfson College, Cambridge CB3 9BB; Email rje36@cam

Image: The syphillis-causing bacterium, Treponema pallidum. 3D4medical.com / Science Photo Library Various 20th century propaganda posters. WPA Posters collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress (LC-USZC2-948, -947 & 944) Albrecht Durer’s (1471–1528) woodcut of a syphilitic man covered in chancres. NYPL / Science Source / Science Photo Library.