Human papillomaviruses

Issue: Viruses and Cancer - 2013

18 February 2013 article

JO PARISH & SALLY ROBERTS

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) are small, double-stranded DNA viruses that infect epithelial tissue, such as skin and the ‘wet’ mucosal epithelial linings of the anogenital tract and oropharynx, generally inducing warts and papillomas. To date, nearly 120 distinct genotypes of HPV have been identified and whilst infections caused by the majority of these types are not a clinical burden, a small number have been shown to induce disease of significant clinical relevance. Some types are linked to the development of non-melanoma skin cancers, and some, such as HPV-6 and HPV-11, are the primary cause of genital warts. A subset of 13 HPV types is associated with the development of cancers of the anogenital tract (cervix, vulva, vagina, penis and anus) and of the head and neck (tonsil, base of tongue and oropharynx). Even within this group of ‘high-risk’ viruses, some types are more prevalent than others; HPV-16 is most commonly associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and head and neck carcinomas, whilst HPV-18 is the most frequent type found in cervical adenocarcinomas.

HPV-induced carcinogenesis

What is it about the high-risk viruses that differentiates their pathogenesis from that of the vast majority of HPVs? This was largely answered when the functions of the viral proteins E6 and E7 of high-risk viruses were compared with those of the non-cancer-causing viruses. These two HPV proteins act in a cooperative fashion to promote cell proliferation so the virus can utilise the host’s DNA replication machinery, and to ensure cell survival such that the virus replicates before the cell dies. The E6 and E7 proteins of high-risk viruses have evolved different strategies to accomplish these functions.

The key role of the high-risk E7 oncoprotein is to induce hyperproliferation of host cells by targeting multiple processes controlling cell-cycle regulation. This includes the retinoblastoma (Rb) family of tumour suppressors that regulate entry into S phase, where DNA synthesis occurs. By binding to Rb and inducing its degradation, E7 induces the release of the E2F family of transcription factors that activate the expression of genes necessary for S phase entry. The host response to unscheduled activation of the cell’s replication machinery is the induction of apoptosis. This is counteracted by the E6 oncoprotein that has evolved several strategies to block this cell signal, including the targeted degradation of the main executioner of this response, the tumour suppressor protein p53.

Thus, through deregulation of two major tumour suppressor pathways (Rb and p53), the viral oncoproteins create an environment that is beneficial for virus replication in the differentiating cell of the infected epithelium. However, since the p53 pathway has a critical role in sensing genomic damage and instigating its repair, the high-risk viruses, through deregulation of p53 signalling have created an environment that promotes genetic instability of cellular DNA that subsequently goes unchecked. Persistent high-risk infections therefore have an increased risk of the emergence of immortal cells, which have a better growth advantage than surrounding cells, and an increased risk of acquiring oncogenic mutations leading to malignancy.

Another characteristic of high-risk HPV types relevant to their oncogenic nature is the tendency of their genomes to integrate into the host DNA. The site of breakage within the viral genome is preferentially restricted to a region encoding the viral transcriptional regulator, E2. The consequence of integration is therefore the severance of the negative feedback signal mediated by E2 upon the expression of E6 and E7, resulting in unchecked expression of these two oncoproteins.

The development of HPV-associated cancer is a late and rare complication of persistent infection by high-risk HPV types and is the end game of a chain of events that unfold over many years. However, infection by these viruses is necessary for the initiation and maintenance of the cancer phenotype and the virus is therefore an important target for antiviral intervention and therapeutic treatments.

Combating HPV-induced disease

To combat HPV-induced disease, clinicians and researchers have developed an arsenal of prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. Nonetheless, HPV-associated disease is still significant, particularly in the developing regions of the world, where high-risk HPV infections and the consequent cancers are rarely diagnosed or treated; cervical cancer remains the most common cancer in women worldwide, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, in these parts of the world the recently developed prophylactic vaccines are not widely available for financial and logistical reasons.

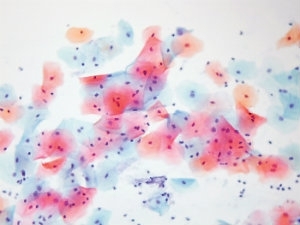

The introduction of cervical screening in 1964 in the UK has been followed by substantial reductions in mortality caused by cervical cancer. When it was realised that HPV was a necessary and sufficient cause of cervical cancer, it was hoped that the detection of HPV DNA sequences in cervical smears could be used to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of cervical screening. Towards this end, the NHS is trialling a new protocol for cervical screening in which women found to have borderline or mild dyskaryosis are routinely tested for HPV sequences. Those women that are positive for high-risk HPV will be sent directly for microscopic examination of the cervix (colposcopy), instead of cytological surveillance every 6 months. Women who are negative, however, will be returned for routine surveillance every 3–5 years. This new screening protocol will reduce the rate of repeat smears, but increase the number of women referred for colposcopy.

Notwithstanding the extraordinary progress that has been made towards the diagnosis and treatment of cervical and other anogenital malignancies in more developed countries, HPV-associated cancers continue to be an important source of morbidity and mortality. In 2010, there were over 6,500 new cases of HPV-associated cancers diagnosed and over 2,000 deaths from these cancers in England alone.

In the UK, since 2008 there has been a national programme for the vaccination of girls aged 12 to 13 using a bivalent vaccine called Cervarix, which targets HPV-16 and HPV-18 that together cause 70% of cervical carcinomas. In 2012, the NHS announced a change in the HPV vaccine used. Gardasil, a quadrivalent vaccine which confers resistance to HPV-16, -18, -6 and -11 is now in use. Trials with both of these vaccines have shown significant protection against HPV-16- and HPV-18-related carcinomas and, in addition, Gardasil has an efficacy of almost 90% against genital warts.

The antigens in both vaccines are virus-like particles (VLPs) composed of the L1 major capsid protein. Due to conformational changes that are required at the surface of HPV virions during virus entry into the host cell, virus entry takes several hours. The presence of VLP-induced antibodies prevents attachment of the virus to the basement membrane underlying the epithelia and entry into host cells. This means that while Gardasil and Cervarix are extremely effective for prophylactic use, individuals that already have a persistent HPV infection cannot benefit from vaccination. It is for this reason that the vaccine is specifically targeted to young girls before they have reached their sexual debut. The prevention and treatment of HPV-associated disease in unvaccinated individuals therefore remains a priority. At present, therapies for anogenital HPV infections are limited. Surgical ablation, which is effective in the short-term but associated with high recurrence rates, and cytotoxic agents, such as trichloracetic acid and podophyllotoxin, are common in the treatment of genital warts, but have issues with patient tolerance. Immune modulators, such as Imiquimod, applied topically to genital warts have high efficacy and reduced recurrence rates, but acute and severe local inflammation can be problematic.

Maintenance of the malignant phenotype absolutely requires the expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins. Targeting these proteins to treat HPV-induced disease is therefore an appropriate strategy. Trials of therapeutic HPV vaccines composed of E6 and E7 peptides in various forms have shown efficacy in the clinical regression of benign and pre-cancerous lesions, but a successful outcome is not so obvious in patients with high-grade cancer.

In addition to the development of therapeutics useful in treating HPV-associated disease, work is on-going to develop antiviral compounds. The inhibition of HPV DNA replication

by chemical inhibition of the viral E1 helicase is one such strategy and, while potent molecules have been developed in vitro, these compounds are not effective in vivo. Similarly, the potential to block DNA binding of E1 or the viral replication/transcriptional regulator protein E2 has been explored, with only a handful of compounds showing activity in vivo.

Undoubtedly, the development of prophylactic vaccines has been an important step in our effort to control HPV infection. However, it is clear that the incidence of some HPV-associated cancers is increasing and, along with high levels of HPV-associated cancers in the developing regions of the world, the race to prevent and treat HPV infection is far from over.

JO PARISH & SALLY ROBERTS

School of Cancer Sciences, Cancer Research UK Cancer Centre, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT; Tel. +44 (0)121 414 7459; Email [email protected], [email protected]

Image: All furures - Science Photo Library.