Viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma

Issue: Viruses and Cancer - 2013

18 February 2013 article

JANE A. McKEATING & COLIN R. HOWARD

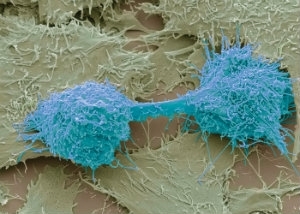

Primary liver cancer, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is the most common liver malignancy with an estimated 750,000 new cases and 695,000 deaths per year, rating third in incidence and mortality in the world. Whilst the majority of cases occur in the Far East and Sub-Saharan Africa, HCC diagnosis is increasing in Europe. Recent Cancer Research UK figures project a 40% increase in HCC in the UK between 2010 and 2030. Whilst incidence and mortality for other common cancers are declining, this cancer represents an increasing public health problem. HCC is a complex and heterogeneous tumour with limited treatment options and poor prognosis due to recurrence and metastases. Hence, there is a real need to increase our understanding of the mechanisms underlying HCC pathogenesis to provide new targets for therapeutic intervention and vaccination.

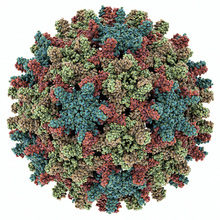

Hepatitis B virus (HBV), a DNA virus in the family Hepadnaviridae, has been implicated in the development of HCC. Depending on the geographic area, more than 50% of HCC cases are attributed to HBV and infected subjects have an approximate 100-fold increase in the relative risk of developing HCC compared to uninfected patients. By comparison, smoking increases the risk of cancer tenfold. In contrast, where HBV prevalence is low, such as the USA, Europe and Japan, chronic hepatitis B is associated with fewer than 20% of HCC cases. These countries have witnessed a marked increase in the incidence of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated HCC, an RNA virus closely related to the flaviviruses.

The liver undergoes rapid regeneration following destruction of hepatocytes, maximising the opportunities for the development of chromosomal abnormalities leading to HCC. The observation that HBV and HCV, two viruses with such widely differing replication strategies, are the major agents predisposing the human liver to cirrhosis and hepatoma suggests an indirect role for infection in the carcinogenic process. Abnormalities arising from prolonged infection with either virus are most likely exacerbated by environmental factors, such as aflatoxin, alcohol abuse or the release of superoxides and free radicals associated with chronic infalmmation.

HBV

The evidence for a causal relationship between HBV infection and HCC is overwhelming. Active HBV infection and HCC share a common geographic distribution and most HCC cases arise in HBV carriers. A landmark prospective study of 22,000 individuals in Taiwan showed that men positive for HBV had over 200 times the rate of HCC, compared to a similar, uninfected cohort. HBV infection may lead indirectly to hepatoma development following chronic liver injury, due to immune attack on virus-infected hepatocytes. Chronic liver regeneration predisposes to tumour development. This concept is supported by the fact that alcoholic cirrhosis predisposes to HCC.

Woodchucks (Marmota monax) infected with the woodchuck hepatitis B virus (WHBV) have provided a valuable model to study the role of HBV in HCC pathogenesis, with the majority of animals infected as neonates developing liver cancer by 3 to 4 years of age. Activation of the N-myc oncogene has been associated with the integration of WHBV DNA in over 90% of tumours; however, this insertional activation of a common oncogene has not been found

in human HCC.

Tumours are usually clonal with respect to the integrated viral sequences, suggesting that integration occurs prior to the expansion of tumour cells, many years prior to the development of cancer. The hepadnavirus genome does not contain a known oncogene: cellular enzymes such as topoisomerase I are thought to be responsible for recombination, which is not restricted to any specific region of the host chromosome. HBV integration promotes genetic instability by undergoing repeated mutations, deletions and inversions. The mammalian hepadnaviruses contain a gene, X, which encodes a trans-activating protein that is absent in the genome of non-oncogenic avian hepadnaviruses; however, conclusive evidence that the X gene is a mediator of hepatocyte oncogenesis is lacking. It has been noted that X may be required for the early stages of oncogenesis, but not for later stages, since HBV gene expression is close to zero in HCC tumours. Unregulated X expression is associated with hepatocyte carcinogenesis in transgenic mice. The surface glycoproteins, or truncated products, may also participate in carcinogenesis but none of the seven HBV polypeptides appear to act as dominant oncogenes.

HCV

Over 75% of individuals parenterally exposed to HCV develop a persistent infection and, among this cohort, up to 5% develop HCC later in life. Although this percentage is small, globally this represents around 9 to 10 million cases at any one time. HCV causes chronic liver injury that can progress to severe fibrosis and cirrhosis. HCV is a positive-stranded RNA flavivirus that replicates in the cytoplasm and does not integrate into the host genome, supporting the hypothesis that hepatocellular carcinogenesis occurs via indirect effect(s) of infection on chronic inflammation and hepatocyte injury. However, inflammation alone is not sufficient to cause HCC since conditions such as autoimmune hepatitis rarely develop HCC. Several HCV-encoded proteins have been reported to play a role in the development of HCC in experimental and transgenic animal systems. However, many of these reports have studied HCV proteins expressed in isolation, raising questions on the physiological relevance of the model systems. Recent advances allowing the assembly of infectious HCV particles in vitro will enable studies to investigate the effect(s) of virus replication on host cellular pathways involved in oncogenesis.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are increasingly a focus of interest in the role of HBV or HCV in hepatocarcinogenesis. HCV replication is dependent upon miR-122, a liver-specific miRNA that plays a key role in tumour suppression, and HBV has been shown to alter the expression profiles of this and other miRNAs. But how these altered profiles predispose hepatocytes to cellular transformation remains to be elucidated.

Conclusion

Most HBV chronic infections are acquired in the first few months of life and such long-term carriers are at high risk of developing HCC in adulthood. For this reason, it is recommended that infants in regions of high HBV prevalence are vaccinated at or shortly after birth. Vaccination against HBV has proven effective, not only in reducing the prevalence of HBV carriage, but in lowering the incidence of HCC later

in life, thus making HBV vaccines the first widely available vaccine against a human cancer.

Antivirals are increasingly effective for the treatment of chronic HBV and HCV infection and, although their use may retard the development of cirrhosis and HCC, there is no definitive evidence that their application can prevent the development of HCC unless administered early after infection and virus infection is resolved. In both cases, surveillance is key in order to identify those individuals at risk of developing HCC: the introduction of HBV vaccines into childhood immunisation programmes over the next two decades will lead to a marked reduction in HCC in countries where the virus is endemic. It is to be hoped that a similar strategy could prove equally as effective to reduce the burden of HCV infection and thus effectively eliminate virus-induced liver cancer in years to come.

JANE A. McKEATING & COLIN R. HOWARD

School of Immunity and Infection, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, Medical School Building, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT; Tel. +44 (0)121 414 8173; Email[email protected]

Further reading

Bouchard, M.J. & Navas-Martin, S. (2011). Hepatitis B and C virus hepatocarcinogenesis: lessons learned and future challenges. Cancer Lett 305, 123–143.

El-Serag, H.B. & Rudolph, K.L. (2007). Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 132, 2557–2576.

Lemon, S.M. & McGivern, D.R. (2012). Is hepatitis C virus carcinogenic? Gastroenterology 142, 1274–1278.

Lok, A. (2011). Does antiviral therapy for hepatitis B and C prevent hepatocellular carcinoma? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 26, 221–227.

Image: All figures - Science Poto Library.