A deadly synergy: the Great War and the Great Pandemic

Issue: World War I

29 May 2014 article

Attention to microbiology was not in the front of minds of politicians, nationalists and military men as the war began. But influenza A is a Darwinian virus driven by the vast unfathomable laws of nature and emergence, re-emergence and resurgence of natural disease and moves with alacrity.

This virus is the supreme opportunist. Our leaders were stumbling towards a fateful decision that would embroil Europe, bankrupt England and finish its Empire, and cause the deaths of over six million soldiers worldwide by war and even more startling a further 80 million civilians by pandemic influenza. To me these two events were not adjacent, one closely following after the other: they were intertwined and synergistic.

The war provided the Perfect Storm conditions for an influenza pandemic to arise; millions of young people in army holding and training camps, some of them gassed and all stressed. During 1917 and 1918, malnutrition and overcrowding in the Home Fronts throughout Europe and the mass movements of soldiers all worked in synergy to allow spread and global dispersion of the virus. In turn, the virus disrupted the war economy in the UK and altered the course of the war. The final great and ultimately unsuccessful challenge, March to May 1918 by Ludendorff, to knock the British Expeditionary Force out of the war was slowed by influenza in the German Army. Within months the virus attack destabilised the Allies on both the Home and Western Fronts such that they agreed an armistice rather than an attack on Germany itself for a true victory.

Public health specialists took action against emerging influenza in 1918 but ignored an early warning signal on the Western Front in 1916

At this point I would not want anyone to conclude that scientists, bacteriologists and doctors, our fore bearers, were inactive: totally the opposite. Pneumococcus vaccines were formulated, disinfectant sprays and masks introduced and social distancing and school closures were started, especially in American cities. Those cities which used all these measures quickly and at the same time, suffered less than comparable ones who hesitated or had a step-by-step strategy.

As the infection quickly gripped England and the world, countless nurses and doctors succumbed. Twenty-three thousand citizens died in London alone. Morbid anatomists risked their lives to collect and store lung samples, which today are the basis of molecular studies to unravel the pathology of the disease. In the British Army influenza casualties of 498,188 exceeded the Battle of the Somme (463,697), but laboratories were set up on the Western Front, filtration experiments started to investigate a viral origin of the disease and macaques imported for animal transmission work.

Bacteriologists identified co-infection of the lung with classical Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. Indeed modern analysis of post-mortem samples from the 2009 ‘Mexican’ pandemic, caused by a distant relative of the 1918 H1N1 virus, showed a remarkably similar pathology.

But at the back of my mind is a nagging query about whether previous herald waves of influenza in Europe and early warning signals were ignored. My students identified two British Army camps where there were serious influenza outbreaks in the winter of 1916, in the huge British Army base on the edge of the sea at Étaples in Northern France in the winter of 1916 and in Aldershot barracks north of London. The Étaples camp housed 100,000 soldiers on any one day and over one million soldiers suffered and recuperated there en route from England to the Western Front or vice versa between 1916 and 1918. From an influenza virology perspective Étaples was on the Picardie migration flight for swans and geese, known now to be carriers of new pandemic influenza viruses, while inside the camp the army had set up piggeries, and hen and duck houses. Pigs are the classic ‘mixing vessels’ since they can be co-infected with avian and human viruses which then re-assort genes, while chicken and ducks are also a conduit for avian influenza to their keepers.

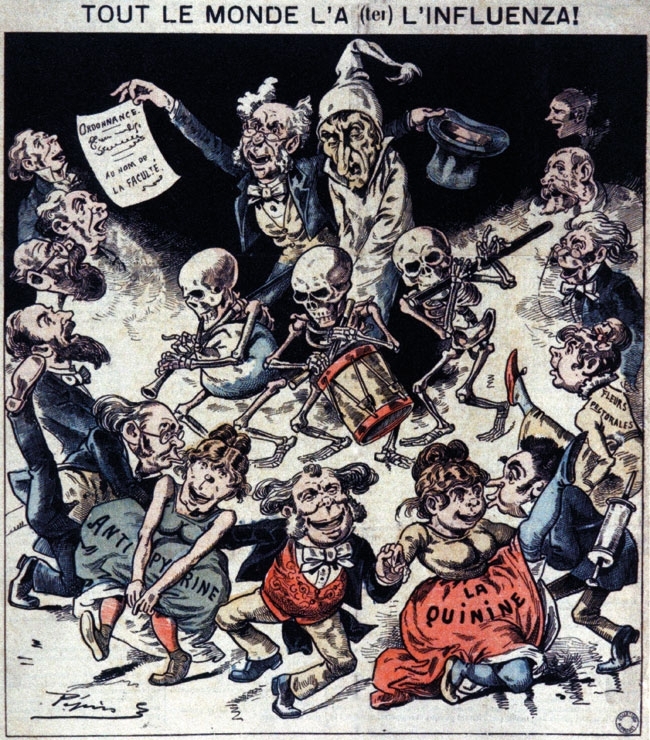

HISTORICAL FRENCH CARICUTURE OF THE 1918 INFLUENZA PANDEMIC

Could the 1916 virus have been widely seeded because of the war while needing a few mutations to enable person-to-person spread, which it accrued in the next two years? Recently, we have identified a link between Étaples and Harvard Medical School in Boston where doctors and nurses criss-crossed the Atlantic between 1916 and 1918 after working at Étaples and who could have, inadvertently, transferred the new virus to the USA from 1916 onwards (Gill and Oxford, in press). We speculate that the final mutations could have occurred there as millions of young Americans congregated in vast army camps in late 1917 and in early 1918.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the 1918 pandemic virus and laboratory studies of a ‘reconstructed’ virus

The advent of specialised real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) whereby traces of virus RNA can be amplified from ancient or formalin-fixed clinical samples opened a scientific window upon the 1918 pandemic.

In August 1998, our combined USA, Canadian, Norwegian and British expedition to Spitsbergen attempted to recover virus genes from frozen Spanish influenza victims who died there in October 1918. At the grave opening, on the mountainside, our team found seven bodies with soft tissue remnants that included respiratory tract and kidney organs. In contrast, Dr J. Hultin, exhuming in Alaska, was more fortunate. He uncovered the lung of a well-preserved frozen Inuit, whom he called Lucy, which had influenza RNA that could be amplified.

In the UK a number of lead-encased bodies in crypts near St Bartholomew’s Hospital and in the North of England have been shown to be well preserved for 200 years. My own group has exhumed three such 1918 influenza victims, but the coffins were either crushed or split or were wood or zinc rather than lead. To date, high-quality soft tissue from the respiratory tree has not been retrieved.

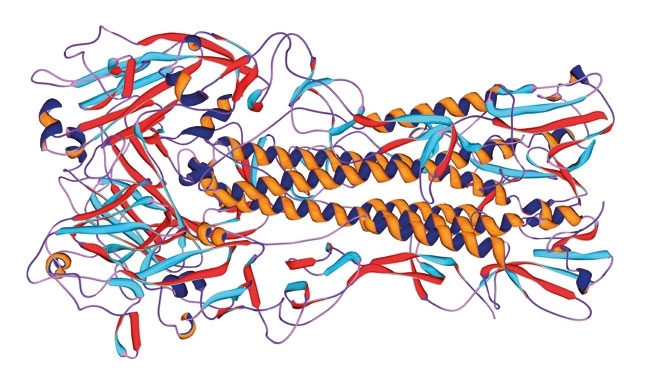

MOLECULAR MODEL OF HAEMOGGLUTININ 1 FROM THE 1918 INFLUENZA VIRUS

Fully infectious 1918 influenza virus has been reconstructed in the USA laboratories by reverse genetics and the virus pathogenicity studied in animal models in category III and IV laboratories. Most surprisingly to my mind, the virus is not overly pathogenic in mice and ferrets. To date, no single gene has shown to be solely responsible for the extremely high human mortality. But we have to acknowledge that only a handful of nucleotide sequences are to hand from the 80 million victims and these show remarkable genetic identity. The surface glycoprotein haemagglutinin (HA) from a sample from my own hospital the Royal London, only has a single mutation compared with a sample from an American soldier who died 3,000 miles away and months apart.

But this single nucleotide change is near the receptor binding site of the HA responsible for attachments of the virus to the upper and lower respiratory tract of birds, pigs and humans, and could be more important than we have thought so far.

An extraordinary and clear message is emerging from this sad tale, which tells us to build our public health infrastructure and continue to expand our epidemiological vigilance and surveillance against all these infectious viruses and bacteria. Virus surveillance at the interface of humans and birds and pigs is recklessly thin. Indonesia has 1.67 billion chickens but has only sequenced 719 influenza viruses and Brazil with 1.27 billion chickens has failed to raise a single nucleotide sequence.

I personally feel we should now set our goals for completed pandemic plans and mine is timed for 2018 when given our speed of travel and nature of overcrowding of our world a new virus whether H2, H10, H7 or H5 could be upon us. With our preparations complete we would then be ‘at the end of the beginning’ as regards protection of all citizens.

But, in a final twist to the story, the Royal Navy, in which my father so proudly served, must have acted as a major conduit whereby the virus reached out to the world in the second wave in November in 1918.

JOHN S. OXFORD

Centre for Infectious Diseases, Blizard Institute and Retroscreen Virology Ltd, Queen Mary BioEnterprises Innovation Centre, London E1 2AX, UK

[email protected]

FURTHER READING

Gill, D. & Putkowski, J. (1985). The British Base Camp at Étaples 1914–1918. Musée Quentovic: Étaples.

Phillips, H. & Killingray, D. (editors) (2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemics of 1918–1919: New Perspectives. Social History of Medicine Series. Oxon: Routledge.

Winternitz, M. C., Wason, I. M. & McNamara, F. P. (1920). The Pathology of Influenza. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Image: AMI Images/Science Photo Library. CCI Archives/Science Photo Library. Laguna Design/Science Photo Library..