Frederick William Twort: not just bacteriophage

Issue: World War I

29 May 2014 article

The discovery of bacterial viruses, or bacteriophage, by Twort was an important milestone in the history of microbiology. It broadened our understanding of the fundamental forms of life that exist in nature and provided a potential route to treat bacterial infections, which has seen a renaissance in the last decade. After his work on bacteriophage, Twort continued his research and made further noteworthy discoveries.

Bacteriophage (Fig. 1, left) has become the tool of the pioneering molecular biologists, such as the eponymously named ‘phage group’ of Hershey, Luria and Delbrück that started in the 1940s and which led to many Nobel-Prize-winning discoveries based around microbial genetics.

FIG. 2. FREDERICK WILLIAM TWORT (1877-1950)

Much has been written about the discovery of bacteriophage by Twort (Fig. 2). He published his work on this ‘infectious disease of the micrococcus’ in the Lancet in 1915. The second scientist credited with the discovery of phage, Felix d’Herelle, published his work in 1917 and his name, bacteriophage (for bacteria eater) has stuck to this day.

In this short article I introduce Twort, a bacteriologist working in the early 20th century, and describe two other significant discoveries he made in the years immediately preceding World War I. I then briefly examine the contrasting impacts of World War I on both Twort and d’Herelle and the impact of their work in the post-war period.

A budding bacteriologist

Twort, the eldest son of a local GP, grew up in Surrey. After a limited education he managed to get up to London to train in medicine at St Thomas’s hospital, aged only 16. After graduating he decided that his career was to be in laboratory research and he found a position at St Thomas’s to start work on bacteria. Later, in 1901, he moved to work at the London Hospital under the noted bacteriologist Professor William Bulloch FRS. It was in Bulloch’s lab that Twort developed into an exceptional experimental bacteriologist. By 1905 he had published his first research papers and had invented a new stain of Neutral Red and Light Green, known later as the ‘Gram-Twort stain’, which was used more widely in microbiology to reveal the fine structure of a number of eukaryotic microbes.

Experimental evolution of bacterial phenotypes

While most of his work was routine bacteriology, Bulloch allowed his scientists to undertake independent research. Around this time the bacteriologist, MacConkey, working at the newly opened Lister Institute, had described a typing system for the Enterobacteriaceae based on fermentation patterns of different sugars. Twort, who was using this system for his routine work, found to his surprise in 1907 that these phenotypes were not stable and that one strain could, over time, change its fermentative behaviour. In a series of experiments, which resemble modern experimental evolution, he serially subcultured bacteria grown in a base medium supplemented with a sugar that this strain couldn’t use. After growing for 14 days ‘to try and induce the microbe to attack the sugar’, the cells were subcultured and the process repeated. He managed to experimentally evolve a number of bacteria, including Salmonella enterica subsp. Paratyphi, to grow on sucrose as a carbon source. In the short term this meant that typing based on fermentative patterns was potentially flawed, but probably more significantly he demonstrated that new phenotypes could be experimentally evolved in controlled laboratory experiments using prolonged selection.

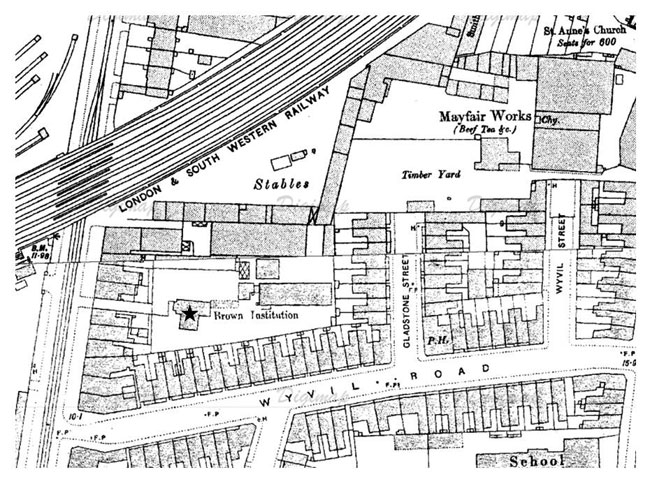

FIG. 3. THE SITE OF THE BROWN INSTITUTION ON THE WANDSWORTH ROAD CA 1890, WITH THE AUTHOR’S SUGGESTION AS TO THE SITE OF THE DISCOVERY OF BACTERIOPHAGE MARKED WITH A STAR. NOTE THE CLOSE PROXIMITY OF SMUT-BELCHING L&SW RAILWAY AND SMELLY BEEF TEA WORKS. THE STABLING WAS FOR THE ANIMALS BEING TREATED AT THE INSTITUTION.

Independence at the Brown Institution

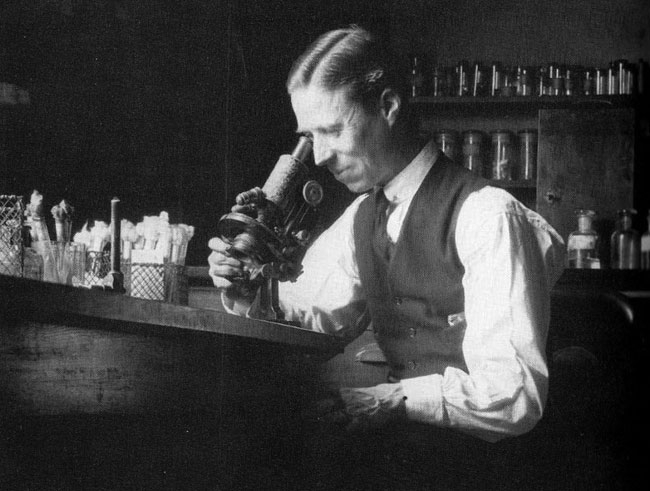

After eight years in Bulloch’s lab, and emerging as one of the best young bacteriologists in the country, Twort was seeking independence and applied for the Superintendentship of the Brown Institution on the Wandsworth Road in Vauxhall, London (Fig. 3). This was really a medical/veterinary position as the institution was set up as an animal hospital for poor families in South London, but he fancied it would give him opportunity to undertake original research and he was duly appointed in June 1909. The building that Twort found was a small one set back behind a row of houses with a large exercise yard and housing for animals. They treated all sorts of animals, but before the war this was mainly horses, which were ubiquitous parts of life and key assets for poor families. It was at the benches of these buildings in an unfashionable and polluted part of London (Fig. 4), that Twort was to discover bacteriophage, but before this he discovered another important aspect of microbial biochemistry.

FIG. 4. F. W. TWORT AT THE BENCH IN THE LAB OF THE BROWN INSTITUTION.

Bacterial growth factors

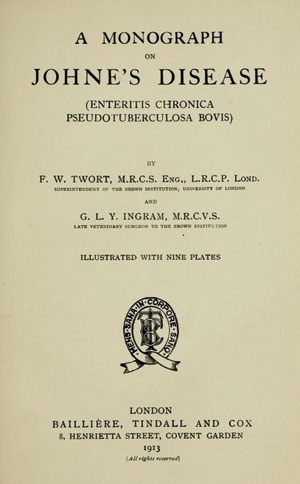

At the Brown his research naturally focused on veterinary-relevant bacteria, including members of the Mycobacteriaceae. Much of his work was on a species of Mycobacterium that causes a wasting disease in cattle and other ruminants and which was known as Johne’s bacillus (Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis). Twort won international acclaim as he was the first to develop a growth medium for this bacterium and he published a widely used monograph in 1913 with his colleague Ingram (Fig. 5). The critical component of Twort’s breakthrough for growing the microbe was that he had supplemented the medium with extract from other dead bacteria. There was clearly some preformed molecule in these extracts that was essential for growth of Johne’s bacillus, which he called an ‘essential substance’. It was not until 1936, when growth factors were known as vitamins, that Twort’s work was recognised and later the ‘essential substance’ in this case was identified as vitamin K.

TWORT & INGRAM’S IMPORTANT MONOGRAPH ON THE JOHNE’S BACILLUS, PUBLISHED IN 1913. INGRAM TRAGICALLY DIED OF TUBERCULOSIS A FEW YEARS LATER.

Captain Twort in Macedonia

Twort’s seminal work on the discovery of bacterial viruses was completed shortly after this in 1913–14, but in 1914 with the outbreak of war the shortage of funding effectively stopped all of Twort’s research. Not out-of-character with some of Twort’s later clashes with the funders, he mentions this in the closing lines of the famous Lancet paper – ‘I regret that financial considerations have prevented me carrying these researches to a definite conclusion’. Instead of doing nothing, Twort joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in late 1915 to run a bacteriological lab in Salonika (now Thessaloniki), Greece (Fig. 6). Again, this was intensive routine work, under oppressive conditions, and any ideas he had of continuing work on bacterial viruses soon vanished. While malaria was the major problem in Salonika, dysentery was also rife and he clashed with senior officers who pronounced it was amoebic dysentery, when Twort, who was examining the specimens, could see it was of bacterial origin. Disenchanted by the army medical hierarchy, he served out his 12-month commission and returned to England in 1917.

CAPT. F. W. TWORT ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS AT THE BASE LABORATORY IN SALONIKA, GREECE, IN 1916.

D’Herelle on the Western front

While the war stopped Twort’s work on phage, it was the catalyst for the French-Canadian microbiologist Felix d’Herelle’s independent discovery of the same phenomenon. In mid-1915, d’Herelle was following an outbreak of dysentery in French soldiers near Paris, when he mixed cell-free filtrates from cultures of Shigella dysenteriae with living bacteria of the same species on agar plates and he observed the familiar rings of clearing that he named plaques. His work was presented to the French Academy of Science in 1917 and despite d’Herelle’s immediate thoughts on how phage might be used to treat patients with dysentery, this was not used as a treatment during World War I.

Post-war and legacy

After the war Twort didn’t seriously pursue his studies on phage, but spent many years looking for ‘primitive viruses’ that he thought he would be able to culture. In stark contrast, d’Herelle was flying the flag for phage therapy across the world and was slowly gathering evidence for its successful application. It was during this period that d’Herelle, who had not acknowledged Twort in any of his work, was forced to recognise that he was not the first to describe phage and the naming of their combined observations as the Twort-d’Herelle phenomenon was recognition of this. For Twort, the war had brought the Brown Institution to its knees and yet he managed to keep it running on a shoestring. His obsession with ‘primitive viruses’ and frequent clashes with funders kept him on the fringes of scientific society, but his work was recognised by his election as FRS in 1929 and appointment as Professor of Bacteriology at the University of London in 1931. However, world war and Twort’s research at the Brown Institution had one more terminal encounter, when in July 1944 a German bomb destroyed the lab where phage had been discovered, leaving us with no way to mark this important site of microbiological history for the many of us 21st Century microbiologists still using and learning more about this intriguing parasite.

GAVIN H. THOMAS

Department of Biology, University of York, YO10 5DD, UK [email protected], @GavinHThomas

FURTHER READING

Biographical information for this article is largely based on the excellent full biography of Twort written by his son Dr Anthony E. P. Twort: Twort, A. E. P. (1993). In Focus, Out of Step: A Biography of Frederick William Twort F.R.S. 1877–1950. Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing.

Duckworth, D. H. (1976). Who discovered bacteriophage? Bacteriol Rev 40, 793–802.

Twort, F. W. (1907). The fermentation of glucosides by bacteria of the Typhoid-coli group and the acquisition of new fermenting powers by Bacillus dysenteriae and other micro-organism. Proc R Soc Lond B 79, 329–336.

Twort, F. W. & Ingram, G. L. Y. (1913). A monograph on Johne’s Disease. London: Balliere, Tindall & Cox.

Twort, F. W. (1915). An investigation on the nature of ultra-microscopic viruses. Lancet 2, 1241–1243.

Image: Fig. 1. AMI Images/Science photo Library. Science Photo Library. Fig. 2. Science Photo Library. Fig. 3. © Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Limited 2014. All rights reserved. Fig. 4. Reproduced courtesy A. E. P. Twort. Fig. 5. Author’s collection. Fig. 6. Reproduced courtesy A. E. P. Twort..