Typhus in World War I

Issue: World War I

29 May 2014 article

Epidemic typhus has always accompanied disasters striking humanity. Famine, cold and wars are its best allies. Typhus, also known as historical typhus, classic typhus, sylvatic typhus, red louse disease, louse-borne typhus and jail fever has caused mortality and morbidity through the centuries, and on the Eastern Front during World War I it led to the death of thousands.

The original description of typhus is thought to have been made in 1546 by Fracastoro, a Florentine physician, in his treatise of infectious diseases: De contagione et contagiosis morbis. His observations during the Italian outbreaks in 1505 and 1528 allowed him to separate typhus from the other pestilential diseases. It also recognised the transmission of typhus from human to human. The term ‘exanthematic typhus’ was introduced in 1760 by the French physician, Boissier de Sauvages. Thanks to PCR testing of dental pulp from ancient remnants of bodies from graves, we now have evidence that typhus and trench fever were involved in the decimation of the besiegers of Douai, 1710–12, during the War of the Spanish Succession, and afflicted the soldiers of Napoleon’s Grand Army in Vilnius in 1812 after their retirement from Russia (Table 1).

TABLE 1. POTENTIAL TYPHUS OUTBREAKS THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MANKIND

In 1909, epidemic typhus was found to be transmitted by Pediculus humanus humanus, the body louse, by Charles Nicolle, and he received a Nobel Prize in 1928 for his findings. Nicolle was able to transmit the typhus from humans to chimpanzees and then to macaques through blood transmission and, finally, from macaque to macaque via a body louse.

FIG. 2. RICKETTSIA PROWAZEKII-INFECTED (A) OR UNINFECTED (B) DEAD P. HUMANUS HUMANUS. THE LOUSE INFECTED WITH R. PROWAZEKII BECAME RED AND DEVELOPED RECTAL BLEEDING BEFORE DYING.

Between 1903 and 1908, Ricketts identified Rickettsia rickettsii (Fig. 1) the agent of spotted fever that is closely related to the agent of typhus. In 1910, he contracted typhus and died in Mexico while conducting his experiments. In 1914, von Prowazek in turn died from typhus after confirming Ricketts’ observations. In 1916, Rocha Lima described the bacterium and named it Rickettsia prowazekii in honour of Ricketts and Prowazek.

Body lice infected by R. prowazekii become red and die shortly thereafter (Fig. 2). Humans are the principal reservoir of typhus during outbreaks. However, a zoonotic reservoir of R. prowazekii exists. In addtion to the detection og antibodies against R.porowazekii in a wide range of domestic and wild animals, R. prowazekii was isolated from the blood of Egyptian donkeys and from the spleens, fleas and lice of the flying squirrel in Florida, USA. R. prowazekii was also isolated from Hyalomma spp. ticks recovered from livestock in Ethiopia and Ambylomma spp. ticks in Mexico.

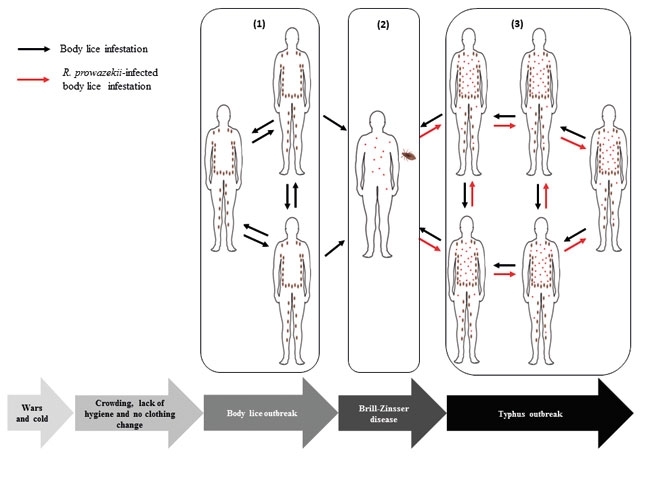

A typhus outbreak requires the occurrence of both bosy louse outbreak and a case of bacteraemic typhus (Brill-Zinsser disease or epidemic typhus) (Fig. 3). These two conditions are often combined in waritme, where stress, lack of hygiene and no-changing of clothes during the winter months are common.

FIG. 3. OUTBREAK OF EPDEMIC TYPHUS. WHEN SOCIAL ORDER IS DISRUPTED, (1) BODY LOUSE OUTBREAK OCCURS AMONG DEFENCELESS POPULATIONS AND (2) THE PRESENCE OF BRILL-ZINSSER CAN INITIATE (3) AN OUTBREAK OF EPIDEMIC TYPHUS.

Body louse outbreak

The body louse is a blood-sucking ectoparasite, specific to humans, that lives and multiplies in clothing. During its life cycle of approximately 35 days, the female louse lays an average of 200 eggs, which can increase the number of lice from a few to thousands on the same individual. The body louse ingests an average of five meals a day, generating extremely dry dejections. It injects various substances when biting that cause itching, compelling the host to scratch vigorously thereby generating lesions on the skin. R. prowazekii enters the skin through these lesions or by the contamination of conjunctivae or mucous membranes with louse faeces containing rickettsiae. Infection through the aerosols of faeces-infected dust has also been reported and is the major risk among physicians.

Clinical manifestations of epidemic typhus

Epidemic typhus is a life-threatening, acute exanthematic feverish disease that is primarily characterised by the abrupt onset of fever with painful myalgia, a severe headache, malaise and a rash. Non-specific symptoms sometimes include a cough, abdominal pain, nausea and diarrhoea. The rash that is characteristic of epidemic typhus classically begins a few days after the onset of symptoms, appearing as a red macular or maculopapular eruption on the trunk that later spreads centrifugally to the extremities (Fig. 4). The rash, which may be hard to see in darker-skinned individuals, except in the axilla, is classically described as sparing the palms and soles. Gangrene and necrosis of toes and fingers that necessitates amputation has been observed. Neurologic symptoms include confusion and drowsiness. Coma, seizures and focal neurologic signs may develop in a minority of patients. The mortality rate varies from 0.7 to 60% for untreated cases, depending on the age of the patient, with a case fatality ratio lower than 5% in patients less than 13 years old. In self-resolving cases, R. prowazekii can persist for life in humans, and under stressful conditions recrudescence may occur as a milder form of Brill–Zinsser disease. R. prowazekii bacteraemia occurs in Brill–Zinsser disease so it can initiate an outbreak of epidemic typhus when body lice are present on the infected individuals.

FIG. 4. DIFFUSE PETECHIAL RASH OF EPIDEMIC TYPHUS.

Typhus in the First World War

The declaration of war by Austria against Serbia in 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand quickly expanded into an uncontrollable global conflict in World War I.

On the Eastern Front, intense shelling of Serbian cities destroyed the existing infrastructure and drove the population to the streets, and at least 20,000 Austrians were taken prisoner by the Serbs. There was a lack of physicians and other medical professionals because they had been seconded to the army, which led to the rapid collapse of the health status of defenceless populations. Malnutrition, overcrowding and a lack of hygiene paved the way for typhus. In November 1914, typhus made its first appearance among refugees and prisoners, and it then spread rapidly among the troops. One year after the outbreak of hostilities, typhus killed 150,000 people, of whom 50,000 were prisoners in Serbia. A third of the country’s doctors suffered the same fate. The mortality rate reached an epidemic peak of approximately 60 to 70%. This dramatic situation dissuaded the Germano-Austrian commandment from invading Serbia in an attempt to prevent the spread of typhus within their borders. Drastic measures were taken, such as the quarantine of people with the first clinical signs of the disease, but attempts were also made to apply standards of hygiene among the troops to prevent body lice infestations (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5. SOLDIERS' KIT BAGS BEING PLACED INTO GAS CHAMBERS TO BE DELOUSED DURING WORLD WAR I.

On the Western Front, although body lice were also endemic among the troops, there was no outbreak of typhus. The situation lacked the R. prowazekii bacteraemia to trigger a typhus epidemic, as had happened on the Eastern Front. Another disease, described for the first time and also vectored by the body louse, was raging in the trenches among the troops. It is caused by the bacterium Bartonella quintana and was named trench fever.

On the Russian front, throughout the last two years of the conflict and during the Bolshevik revolution, approximately 2.5 million deaths were recorded. Typhus was latent in Russia long before the beginning of World War I. The mortality rate rose from 0.13 per 1,000 in peacetime to 2.33 per 1,000 in 1915. Soldiers and refugees imported typhus and propagated it across the country. It was during the hard winter of 1917–18 that the biggest outbreak of typhus in modern history began in a Russia that was already devastated by famine and war. The great epidemic started in the big cities and eventually reached the distant lands of the Urals, Siberia and Central Asia.

After World War I, between 1919 and 1923, there were five million deaths in Russia and Eastern Europe because of a third disease vectored by body lice, relapsing fever and caused by Borrelia recurrentis.

Conclusion

Epidemic typhus is an unpredictable disease that can suddenly re-emerge when social organisation is disrupted, as was observed in 1997 among Burundi’s Civil War refugees in central Africa. Wars are optimal conditions for body louse proliferation and their associated diseases. Thus, the control of lice with the combination of oral Ivermectin, clean clothes and insecticides will help to avoid disasters caused by typhus, trench fever and relapsing fever during humanitarian catastrophes.

REZAK DRALI, PHILIPPE BROUQUI AND DIDIER RAOULT

Aix Marseille Universite, URMITE, UM63, CNRS 7278, IRD 198, Inserm 1095, 13005 Marseille, France and Institut Hospitalo-Unversitaire Mediterranee Infection, 13005 Marseille, France

Corresponding author Tel. +33 491 32 4375 [email protected]

FURTHER READING

Bavaro, M. F. & others (2005). History of US military contributions to the study of Rickettsial diseases. Mil Med 170 (Suppl. 1), 49–60.

Bechah, Y. & others (2008). Epidemic typhus. Lancet Infect Dis 8, 417–426.

Raoult, D., Woodward, T. & Dumler, J. S. (2004). The history of epidemic typhus. Infect Dis Clin N Am 18, 127–140.

Tschanz, D. W. (2008). Typhus Fever on the Eastern Front in World War I. Insects, Disease and History Website, Entomology Group of Montana State University (accessed 18 January 2008).

Zinsser, H. (1935). Rats, lice and history: A chronicle of pestilence and plagues. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers.

Image: Fig. 1. Coloured electron micrograph of a bacterium of the genus Rickettsia. Fig. 2. Reproduced from Houhamdi, L and others (2002). J Infect Dis 186 1639-1646; license no. 3337041496430; Oxford University Press. Fig. 3. Rezak Drali, Philippe Brouqui and Didier Raoult. Fig. 4. URMITE (Unite de Researche sur les Maladies Infectieuses et Topicales Emergentes). Fig. 5. Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine/Science Photo Library..