Black History Month: celebrating the work of black microbiologists

Posted on October 9, 2020 by Laura Cox

This October, we will be examining how black microbiologists have shaped the field of microbiology. This post will be the first of four this October and will explore the research and lives of Professor Ruth Ella Moore, Professor A. Oveta Fuller and Onesimus, the Boston man credited for early inoculation practices.

Ruth Ella Moore

In 1933, a time of rampant racial and gender discrimination, Professor Ruth Ella became the first African-American woman to gain a PhD in the natural sciences. In addition, she is believed to be the first African-American of any gender to complete a PhD in Bacteriology. During her scientific career, Professor Moore had a wide-ranging interest in microbiology, with publications on tuberculosis (TB), the microbiome and tooth decay.

Professor Moore started her scientific journey at Ohio State University, where her dissertation focused on the bacteria that causes TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. At the time, TB was an extremely important disease in the context of public health and was the second leading cause of death in the US. All research conducted into TB at this time was hugely valuable, and Professor Moore’s theses were referenced in several ground-breaking articles that improved the understanding and treatment of the disease, ultimately leading to its control in the US.

Just seven years after completing her PhD, in 1940, Professor Moore was appointed Assistant Professor of Bacteriology at Howard University. During her time at Howard, where she stayed for the rest of her career, Professor Moore spent time as the institution’s first female department head, holding the Head of the Department of Bacteriology position for a number of years. Professor Moore continued to research micro-organisms until her retirement in 1973 and published articles on a range of topics, including how micro-organisms in the gut respond to antibiotics, which is some of the earliest research into the microbiome.

Onesimus

In Boston, in 1721, a smallpox outbreak threatened the lives of thousands of residents. The disaster was averted by a man named Onesimus; an African-American previously enslaved person who shared his knowledge on inoculation. In doing so, Onesimus prevented hundreds of deaths and provided vital evidence to inform the development of the first vaccine.

By no means is his story a happy one; Onesimus was taken to America from North Africa, and made to work as an enslaved person for the minister Cotton Mather. During a local smallpox outbreak, Onesimus went to Mather and explained the method of inoculation he had been given in Africa. With thousands of lives at stake, they took the desperate step of administering tiny doses of smallpox pus from those who had already been infected and intentionally administering the pus into small cuts of people who had not been infected with smallpox before. The measures worked, and the death rate from the outbreak fell to 2%, when other smallpox outbreaks at the time had a death rate as high as 17%.

Smallpox is caused by the now-eradicated variola virus, and before Onesimus’ inoculation technique, there was no known treatment or preventative method in the western world. In 1716, Mather wrote to the Royal Society in London, explaining what Onesimus had told him, and the technique was trialled during an outbreak in London, decreasing the fatality of the disease. Without the early inoculation efforts, Edward Jenner would not have developed vaccination using cowpox pus in 1976.

A. Oveta Fuller

A. Oveta Fuller is an Associate Professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan. She is an expert in Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and is best known for the discovery of a B5 receptor on the surface of HSV. The discovery of this receptor played a significant role in improving the understanding of HSV and the cells it infects.

Dr Fuller has been based at the University of Michigan since 1988. Here, she heads a research group and teaches on a course titled ‘Global impact of microbes: fieldwork'. In addition to her teaching and research activities, Dr Fuller is passionate about making science more accessible to communities and has developed a science-based education programme that works with community leaders and clergy to address health inequalities. In particular, this programme, called the ‘Trusted Messenger Intervention’ focuses on awareness, testing and prevention of HIV/AIDS.

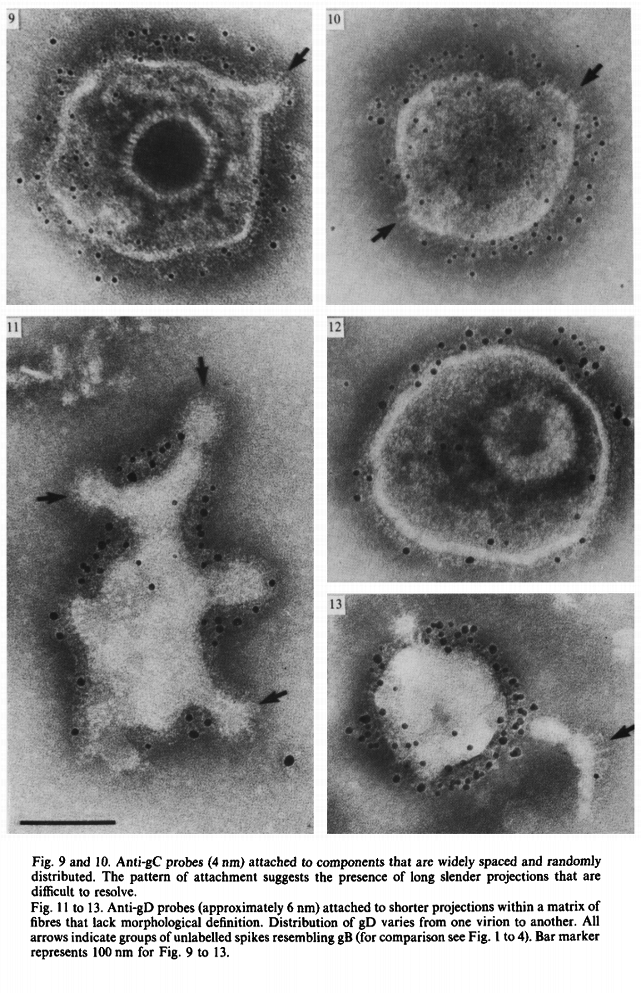

In the Journal of General Virology, Dr Fuller and colleagues authored a research article on how pig cells respond to different types of Herpes simplex virus, research which led to a number of patents on Herpes virus entry receptor proteins and associated antibodies. Professor Fuller contributed to another article in the journal discussing the different spike proteins visible on the viral envelope of HSV.

We will be publishing more blogs highlighting the work of black microbiologists this month. If you would like to nominate someone for us to include, let us know on Twitter.