Diving for antibiotics

Posted on August 24, 2020 by Emily Addington

In this blog post, Emily Addington describes her experience developing an outreach project called 'Dive for Antibiotics'. Emily carried out this project with a grant from the Microbiology Society and presented her project at the President's Roadshow in Strathclyde.

Emily giving a talk about the project to divers at the Project Baseline: Loch Long annual weekend in 2019.

This has been an interesting year for microbiology. Globally, we have seen countries enter lockdown, implementation of social distancing from strangers and loved ones alike, and major changes in our lifestyles - all due to a microbe. It has been a staunch reminder to the world how important microbiology can be to our daily lives; that microbes are all around us and some can be deadly unless we have options to prevent or treat them. It has also emphasised in a major way that we need a science-literate public and government. Science-outreach is an important part of this and as scientists we need to be able to make science accessible and engaging to non-experts.

I’ve run the Dive for Antibiotics (DFA) outreach project since early 2018 with two main aims:

- To generate useful data on marine Actinobacteria and potentially discover novel species with bioactive secondary metabolites.

- To engage and educate divers about microbiology, antibiotic discovery and science in general.

Through social media, including Instagram, Facebook and Twitter, the project has also able to reach the general public, hopefully being of interest to those who previously had a limited education about microbiology. It’s my hope to help inspire the public to become passionate about the microbial world around them and to realise how important it is to our everyday lives; how critical it is to our health, and how fascinating and beautiful it can be.

One of our volunteer divers collecting sediment from the seabed whilst diving.

The project was born out of my interest in isolating marine Actinobacteria. I then tested these to see whether they produced antimicrobial compounds that could kill the ESKAPE pathogens. I began working with Streptomyces in 2017 when I moved to Glasgow. One of the many things that surprised me about Scotland was that it has an enormous diving community made up of incredibly passionate individuals who dive lochs, wrecks, caves and the open ocean. The first diver I spoke to had never heard of Actinobacteria, wasn’t aware that bacteria produced antimicrobial compounds, and was pretty confused over why I wanted him to bring me a bunch of marine sediment from his next dive (I was similarly baffled when he began talking about buoyancy compensator systems, wings and rebreathers).

My first isolations from Scottish marine sediment yielded an astounding number of Actinobacteria and from there I started to recruit volunteers from diving groups on Facebook who would be willing to collect more sediment for me. I got a fantastic response from numerous interested divers, who were all aware of the antibiotic resistance crisis and keen to send in samples from their dives. Moreover, divers had a lot of questions about the process of antibiotic discovery, from isolation, to lab, to clinic and I found chatting to non-scientists about microbiology an enjoyable and rewarding experience.

My little sediment collection side-project became an actual project, and I applied for a Microbiology Society outreach grant and was lucky enough to be awarded it. This meant I could fully fund the project, including buying media and other supplies. A DFA Facebook page, Twitter account and Instagram were set up as more and more divers became interested in collecting sediment for the project.

A marine actinobacterial isolate found during the DFA project showing antimicrobial activity against the pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

In the two years since, DFA has run a sampling competition (with a prize for the sediment sample which provided the actinobacterial isolate capable of killing the most ESKAPE pathogens), been sent sediment from around the world, and found a number of interesting Actinobacteria isolates with antimicrobial activity. I’ve given numerous talks about antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance, antibiotic discovery and had the opportunity to collaborate with fantastic diving organisations such as Project Baseline: Loch Long and Wreck & Cave.

The DFA social media pages document the journey of sediment samples so that divers and interested members of the public can see the steps that go into discovering a novel antimicrobial, as well as how general microbiology is carried out in the laboratory. I love watching divers cheer on their isolates, and nothing is more rewarding than speaking to the divers and hearing how interested they are in the project, the techniques and the microbiology. Outreach has been rewarding in so many ways for me and has helped keep my curiosity and passion in microbiology alive when the struggles of my main PhD project have been wearing. I’ve had the opportunity to isolate Actinobacteria from underwater caves that have never previously been explored by humans, I’ve learnt more about wrecks and diving sites than I ever thought I’d know, and I’ve been given 250-year-old beer from a sunken cargo ship to isolate from (yes, the beer smelled just as revolting as you’d imagine).

Divers for the DFA project collect sediment from their dives, recording the location and depth of the sample along with any other useful information.

At the beginning of this year before we all went into lockdown, I had the privilege of talking about the DFA project at the Microbiology Society 75th Anniversary Roadshow at the University of Strathclyde. It was one of the first opportunities I’d had to present the project to fellow microbiologists of all career stages and the response I got was enthusiastic and humbling. I walked away with a number of new ideas for the project and offers from microbiologists who were keen to get involved. Unfortunately, with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic ongoing, time in the lab is limited. I am now a final-year PhD student, meaning opportunities to work on the project have become more limited. However, it’s my hope that in the next few months I’ll be able to put these new ideas to work and see the project grow further. I hope that my experience inspires other early-career researchers to engage in science outreach, particularly as I think it is now more important than ever before. I can absolutely and wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone who is considering it – do it, you won’t regret it!

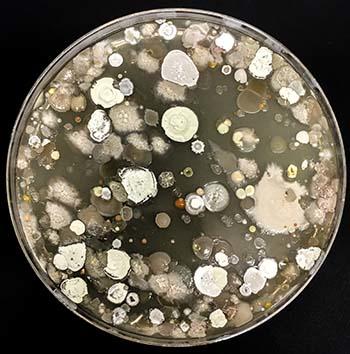

A plate of isolated bacteria from a collected marine sediment sample.