Fighting infectious fungi with vaccines

Posted on July 25, 2012 by Rebecca Way, University of Aberdeen

With antifungal treatments failing due to increasing resistance to antimicrobials, fungal infections are emerging as a silent killer in the healthcare setting. Scientists are researching strategies to overcome this problem and are trying to prevent infections by vaccination.

A review of progress to date "Fungal cell wall vaccines: an update" features in the July special issue of the Journal of Medical Microbiology.

Research carried out in animals, and in Phase I clinical trials in humans, aims to develop a fungal vaccine for clinical use. However, the process is not straightforward as bringing a vaccine to human trial stage can cost $3-4 million dollars, and may be hindered by regulatory barriers faced in clinical development.

Candida albicans is one of the more common fungal pathogens that can colonize skin and mucous membranes all over the body and, while normally harmless, can cause candidiasis - or thrush - infections like vaginitis. If the fungus enters into the bloodstream, and spreads around the body, it becomes life-threatening in some cases. There are many other types of fungal infections which can be just as harmful and are also increasing in prevalence globally.

The rise in opportunistic fungal infections has seen much press coverage recently. These hospital-acquired infections are associated with a high mortality rate of approximately 40-50%. Infections thrive in certain patients; those with weakened immune systems, receiving cancer chemotherapy, or heavy treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, are susceptible to acquiring C. albicans and other invasive fungal infections. Risk of infection is not limited to immune-deficient patients and includes intensive care patients, patients with healing open wounds, and newborn babies.

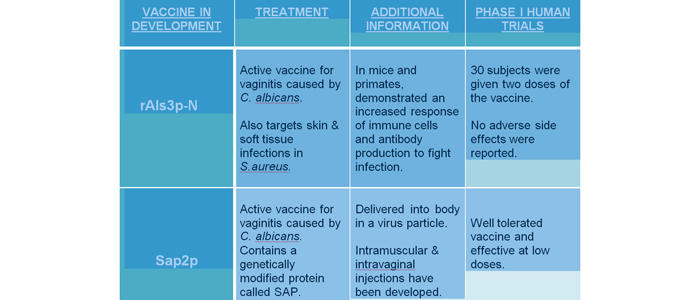

There have been different vaccine strategies for 'active immunization.' Two promising candidates that have gone through Phase I clinical trials against C. albicans are described below. An active vaccine is created containing a live but attenuated (weakened) strain of C. albicans (or other pathogen) with an adjuvant chemical that helps stimulate the required immune response. This allows production of antibodies against the fungal antigens in the vaccine, and induces protection against the infection. Active vaccination is not ideal for immune-suppressed patients, as their immune system is not strong enough to produce the antibody response seen in healthier individuals. Another passive form of immunization would need to be developed for these individuals.

A live attenuated vaccine called rAls3p-N has been developed and was recently tested in humans after positive findings in mice and primates. It demonstrated a high immune response leading to antibody production to fight C. albicans infection, preventing vaginitis. In human trials, 30 subjects were administered two increasing doses of vaccine and no side effects were reported. The increased immune response suggests this vaccine provides protection against C. albicans. Another active vaccine, Sap2p that prevents vaginitis caused by C. albicans has also gone through Phase I trials, and shows tolerability and efficacy in humans.

Trials of other vaccines in mouse models have shown promising data. One problem with using mice is that they have a very different immune response to Candida. Unlike mice, humans exposed to Candida develop immune responses early in life, so primate models may be better models for human infection.

There are still challenges yet to overcome associated with the high costs and risks of developing a vaccine. Gaining the technical skills required to manufacture, store and transfer 'live' vaccines is required. Preparing antigens for use in human studies may require further evidence, for regulatory authorities such as the Food & Drug Administration in the US to approve and accelerate vaccine development. Further exploration into gaining data in humans will promote this exciting research area.