Genomic Insights into Hypervirulent Klebsiella in Ireland

Hi! My name is Mark Maguire, I am a PhD candidate in the Antimicrobial Resistance and Microbial Ecology (ARME) group at the school of Medicine in University of Galway, Ireland. My research focuses on the spread of antimicrobial resistance and virulence associated genes.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a well characterised opportunistic pathogen responsible for healthcare associated infections. Classical Klebsiella pneumoniae (cKp) commonly affects immunocompromised patients while hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) is associated with severe, community acquired infections in otherwise healthy hosts. These infections are often characterised by liver abscesses but can metastasize and spread to multiple body sites via the bloodstream. The convergence of hvKp with multidrug resistance, especially to carbapenem antibiotics, is an emerging public health threat.

The transition from cKp to hvKp is mediated but the acquisition of a number of virulence loci which are encoded either on a virulence plasmid (pVir) or an integrative chromosomal element (ICE). The pVir encodes the rmpADC operon, which upregulates capsule production and confers the hypermucoid phenotype, this can aid in evading the immune system. The iuc and iro operons encode for the siderophores aerobactin and salmochelin respectively. These can aid in chelating iron, which is essential for bacterial survival in iron poor environments. The gene peg-344 is also present on pVir and has been demonstrated to be essential for full hypervirulence. The chromosomal ICE encodes another siderophore, yersiniabactin (ybt) and colibactin (clb), a toxin capable of damaging eukaryotic cells.

Previous work identified the first hvKp isolates in Ireland in 2019 which formed a monophyletic cluster in the southeast was associated with multiple healthcare facilities. Our study aimed to assess the genetic relatedness of all the hvKp ST23 isolates collected in Ireland between 2019 and 2023, and investigated the resistome, virulome, plasmid content and phylogenetic relationship of these isolates.

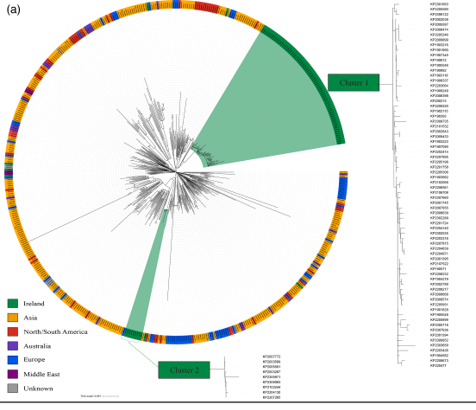

Genomes for all K. pneumoniae ST23 collected in Ireland between 2019 and 2023 were recovered from the Galway Reference Laboratory Service (GRLS). These genomes were collected in eighteen healthcare facilities as part of the national Carbapenemase producing Enterobacterales (CPE) surveillance programme. These genomes were predominantly from asymptomatic rectal screen swabs (66%) while the remainder were from sites of infection or the hospital environment. All K. pneumoniae ST23 genomes available on Pathogenwatch in the same time period were also downloaded. To assess the genetic relatedness of these isolates we conducted core SNP analysis on all genomes. This analysis revealed two distinct clusters of Irish isolates linked to different geographical regions, one in the South and Southeast and the other in the East (Figure 1).

Since only draft assemblies were available, we used a tool called platon to predict the chromosomal and plasmids associated contigs and determine the location of the resistance genes. Four resistance genes (blaSHV-190, fosA6, oqxA5 and oqxB12) were predicted to be encoded on the chromosome of almost all isolates. Greater variability was noted on the plasmids contigs which varied from zero to 17 additional resistance genes, including detection of the blaOXA-48 gene in 83% of isolates. The carriage of these additional resistance genes corresponded to greater levels of phenotypic resistance in those isolates. All isolates carried the replicon associated with the virulence plasmid and all isolates which carried the blaOXA-48 gene also carried the incL replicon, commonly associated with the pOXA-48 plasmid.

To assess the virulence phenotype, we carried out in vivo studies using a murine infection model. Eleven isolates were selected for the murine infection study to investigate the if there were differences in the virulence phenotype between isolates collected from invasive infections, asymptomatic carriage or the environment. Surprisingly, there was little difference in the virulence phenotype between isolates collected from different sites or between isolates which formed part of one of the clusters versus those not in any cluster. All isolates tested displayed a level of virulence consistent with the hvKp pathotype. We also investigated patients from whom hvKp was isolated on multiple occasions. We observed that in some cases asymptomatic carriage persisted for up to 2 years while some cases progressed to cause severe infection.

This study highlights the relatively high asymptomatic carriage of hvKp in Irish patients. The detection of these isolates was mainly incidental: most were only detected because they also carried a carbapenemase gene. It is possible that a much larger number of hvKp ST23 are circulating in the community and in hospital patient populations. There is currently no reliable methods or screening protocol for the detection of hvKp in either of these settings. The absence of such methods means that the number of hvKp may continue to be underestimated, which limits our ability to detect and control it in the healthcare setting.