Get to know the President: how did I get here?

Posted on August 10, 2020 by Professor Judith Armitage

In this blog, Judith Armitage, President of the Microbiology Society reflects on her career pathway and how her passion for microbiology has shaped her life.

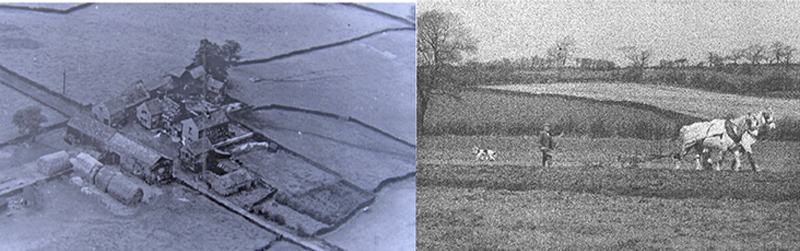

I was born at Windmill Farm, in Shelley. Shelley is a village six miles outside of Huddersfield, on the Pennines. My parents were both children of Pennine farmers and were expected to continue the tradition; indeed, a cousin looking into the Armitage ancestry gave up in the 1700s as all he found were farmers with one or two cottage weavers. All the women were farmers wives, sometimes after a brief period spent as a maid.

I spent a lot of my childhood on my paternal grandfather’s farm, Schole Hill Farm in Penistone. Both my grandfathers still ploughed with horses and one grandfather taught me three things I would need in my future: how to ride a carthorse, how to build a dry-stone wall and how to hand milk a cow. I was a great disappointment to him.

The Second World War probably saved me from the life of a farmer’s wife. Both of my parents – although they had passed their 11 plus exams and gone to the local grammar schools – had to leave school as soon as they could, to earn money for the family. My father would have followed his father but was conscripted into the navy. When he came home after seeing the world, he decided the future of hill farming was limited and became a policeman. He also decided that his children would have every educational opportunity possible.

I went to a small girls grammar school which sent few pupils to university – and if they went, it was to one of the northern universities. The south was alien country. My parents went to London on their honeymoon, I went once for a hockey weekend and that was our collective experience of London.

Why did I go to university to read microbiology? I had inspirational biology teachers: Miss Evans and then Mr Bill. They bought new microscopes, and, at age 16, I looked at pond water for the first time and was hooked. That invisible world of creatures dashing around and interacting with one another drew me in. Microbiology was what I wanted to do for my degree.

Why University College London (UCL)? It was 1969 and I wanted to see something of life. UCL was in the centre of London and therefore, at the time, the centre of the world as I saw it. I had an amazing time. I discovered food, art, theatre and music of all types (I’ve probably seen every classic rock band of the 1960s and 70s). I also did some work.

I did well and discovered I really did like microbiology and became fascinated by bacterial behaviour – how tiny organisms with no internal organisation could apparently make decisions was amazing. It was also here that I met John, who would eventually become my husband. We were both offered PhD places – his in Physiology, mine in Botany and Microbiology, supervised by David G. Smith – working at opposite end of a corridor running the length of the site at UCL Gower Street.

David was genuinely interested in bacteria of all sorts. He suggested I look at why the enteric bacterium Proteus mirabilis changed from a short rod with a few flagella into a 100 micrometre long multinucleate highly flagellate filament. When put onto an agar surface, they would swarm in rafts for a centimetre or so, then divide back into rods; setting off again a couple of hours later and forming a series of rings over 24 hours as the colony spread over an agar surface. David gave me this problem and then basically let me just get on with it.

The other two graduate students in David’s lab worked on different problems, indeed very different species, so we were free to explore. We read papers-in the library- and if there was a new method described, we’d give it a go. These were the days before molecular genetics, genome sequences and so on. Things were cheaper, simpler and, to a large extent, relied on combining observational techniques (such as light and electron microscopy) with biochemistry. Biochemistry usually relied on homogenising litres of bacteria and measuring rates of one chemical changing into another. This, combined with observation of behavioural changes, was put into hypotheses and tested by modifying what you had done before. It was all great fun and I suppose much as science had been done for decades, but after 3 years I had to decide what to do next.

Initially I did not consider being an academic. There were only three female graduate students in our department and no senior female Principal Investigators. The women were the technicians. However, in the neighbouring Biochemistry department was the wonderful Patricia Clarke. She had read Biochemistry at the University of Cambridge, had taken part in microbiology practicals supervised by Marjory Stephenson and after the war and a career break to raise two children, she had moved to Colindale. Pat got a lectureship at UCL in 1953 in competition with 54 men, and by the time I was there in the early 1970s she had become the world’s leading expert on Pseudomonas biochemistry. She was to go on to be awarded a Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1976 – still a very rare achievement for a woman back then. She saw something in me and became a mentor and I doubt I would be where I am today without her help.

As a woman in an almost all-male environment, you tended to be invisible, patronised, or occasionally treated inappropriately. For example, my very charming Head of Department gave graduate students membership of the Wine Society, but he gave mine to John, my then boyfriend as it wasn’t appropriate for me, as a girl, to be a member. I still remember with horror my first Society for General Microbiology conference at a university in the midlands. I entered as a terrified young woman and was faced with a sea of, what to me looked like, grey haired old men in groups. They all knew each other and ignored me. I was alone and miserable and spent my time in my room feeling this wasn’t and never would be my world.

Pat Clarke, however, encouraged me to keep going. When the Royal Society and the Lister Institute both advertised independent research fellowships, she encouraged me to apply and acted as one of my referees although I had never worked with her. She also gave me some very insightful advice: Don’t follow fashion as fashionable areas are already full of ambitious men and you won’t compete; find something that fascinates you, make your own niche and stick to it. It may take time, but if it interests you, you can make other people interested. So, out went thoughts of working on E. coli and in came Rhodobacter sphaeroides: not as a tool to study photosynthesis, but as an organism to study bacterial ‘decision making’. And so, a purely curiosity-driven question was born: what are the decision making mechanisms that make R. sphaeroides swim towards oxygen when grown aerobically, but away from oxygen when grown photoheterotrophically?

In next week's blog, Judith will continue to reflect on her career and what she has learned during her time as a microbiologist.