Global Accessibility Awareness Day: Tanya Horne

Posted on May 18, 2023 by Tanya Horne

Global Accessibility Awareness Day is celebrated today, 18 May, and its purpose is to get everyone talking, thinking and learning about global accessibility. To mark this day, we interviewed Microbiology Society member Tanya Horne about her experience of navigating academia with a disability and the importance of accessibility.

Could you tell us about yourself?

My name is Tanya, and I have a growing love for all things bacteriophage and phage defence systems, especially how happily (or not!) they co-exist when you throw in a lot of other mobile genetic elements and defences. This can have profound implications for horizontal gene flow, and by extension pose huge challenges to human health such as antimicrobial resistance. I’m currently exploring these themes as a PhD student based within the Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences at the University of Liverpool.

I was diagnosed with ovarian cancer during the first year of my PhD. The side effects of the treatment I received will affect every day of my life, forever, which of course has a big impact on my day-to-day as a postgraduate researcher. I am always very happy to chat about this, and grateful to the Society for inviting me to help raise awareness around accessibility.

It’s Global Accessibility Awareness Day on 18 May 2023; will you be doing anything to raise awareness?

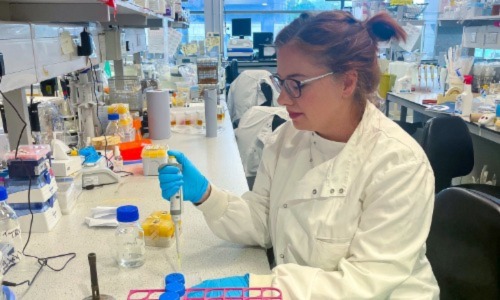

I will be spending the day working on my PhD project, trying to be thankful that I’m currently well enough to be able to sit at a lab bench, and very much hoping that this interview will help raise awareness of this important issue.

As someone studying microbiology who has recently gone through a cancer diagnosis, could you tell us about some of the challenges you have faced?

It’s been an extremely challenging time. As a result of my treatment, I suffer from joint and pelvic pain that can be severe. I also have to manage the symptoms of cancer induced early menopause as best I can; this has included a lot of memory impairment, which has been very frustrating and difficult to manage alongside a very technically challenging PhD! I’ve adapted as best I can in the lab by working as efficiently as possible on days when the pain is less severe and taking adequate rest when needed. Through trial and error, I’ve also found effective methods to minimise physical discomfort and cognitive impairment. These tend to be simple and timeworn: regular walks, mnemonics, having a regular routine, etc.

My Doctoral Training Programme, lab mates and supervisors Professor Heather Allison and Professor Jay Hinton are very supportive, which makes a big difference. For example, my DTP provided paid sick leave for 12 weeks – at the time, this gave me one less thing to worry about and enabled me to concentrate fully on surgery and recovery. They also later approved my application for a funded extension, which means I can better pace myself through the last two years of my studies, better safeguarding my health and ensuring I reach my full potential despite cancer.

Overall, despite the obstacles, I’d say things are working very well at present and that I’m making good progress.

What are some of the access requirements people living with a cancer diagnosis might need as a result of their diagnosis that others may not have considered?

I think this is hugely variable – someone’s requirements will depend on lots of different factors including their age, general health, and treatment status. I also think their requirements are likely to change over time – again, depending on lots of different factors. My own requirements can change day to day.

Although I much prefer to attend meetings and conferences in person, I think it’s wonderful that remote attendance is now much more available – and the norm – than ever. It’s very reassuring to know that if I’m ever immunocompromised again, I can still safely take part in our weekly lab meetings in this way. Heather and Jay will also regularly ask me whether there’s anything more they can be doing to support me, which is wonderful – there’s no better way to ensure you’re maximizing support and accessibility for a student post cancer diagnosis than asking them what they need rather than making assumptions.

Is there anything you wish you had known before your diagnosis that would have made going back to the lab easier post diagnosis?

I had no idea until fairly recently that The Equality Act considers a diagnosis of cancer as a disability, and that this meant I had the right to request reasonable adjustments and support. This was despite being very proactive and seeking support upon my return to the lab from a wide range of university staff and departments. Had I known, I would have been able to access specialised support and advice which I’m certain would have enabled my return to go much more smoothly. I now spread awareness of this as best I can in the hope that future students in my position will have a much easier time than I did.

The uncomfortable truth is that the university was completely unprepared for my situation and didn’t know how to support a student with a cancer diagnosis - there was simply no roadmap in place, and although of course people were sympathetic and wanted to help, no one seemed to know what this should look like. I was told more than once that if I were a staff member, there would be a plan and a system of support in place. Well, with respect, that's not good enough. Students aren’t immune to cancer; the sad fact is that there will be more diagnosed after me, and they need to be as well supported as staff.

We must do better - and I include myself in that. I hadn't given any of these issues much thought until I found myself in that situation. Now that I have thought about it deeply, I of course recognise the immense challenges, not least funding, that stand in the way of truly universally accessible lab facilities such as adjustable height benches and equipment. It's not something we can fix overnight, and is something that will require wholescale, long-term cultural change as well as financial investment.

Thankfully, Microbiology is intrinsically more accessible to work in than a lot of other biological sciences. Whatever I'm working on can usually be popped in the cold room or freezer if I suddenly develop pain, and I can get on with some computer-based work – from home if needed - until it passes. I'm mindful that if I were working with larger, more complex organisms with say a feeding schedule or other needs, that probably wouldn't be the case!

Is there any advice that you would give to other people living with a cancer diagnosis who are working in (or hoping to work in) science?

My advice, particularly to those newly diagnosed, would be this: be mindful of how all of this is going to impact you psychologically. Practical considerations such as access requirements and working adjustments are of course an essential consideration, but it’s largely underappreciated just how heavy a toll cancer takes on your mental health. This is especially true after you’ve finished with treatment. The unfortunate fact is that it’s never really over, and the vast majority of other people with a cancer diagnosis that I’ve spoken to say the period after treatment ends was by far the toughest time for them, mentally. The good news is that you can do things to help prepare you for, and mitigate, this impact. Seek as much support as you can, even if you don’t think you’ll need it. For example, Macmillan Cancer Support provide free, rapid access therapy sessions that I would strongly recommend to everyone in this position.

Do you think more needs to be done to support people living with a cancer diagnosis studying or working in science?

Yes, absolutely! With that in mind, alongside a fellow PhD student from another Institute, I’ve revived the University’s Cancer Support Network to help provide informal peer support. We meet once a month, and our conversations make me feel much less alone.

Studying for a PhD is inherently difficult, and challenging – as it is supposed to be. During this process, life goes on of course: we will all experience some type of ill health, which for some of us will be a critical illness. This will have a huge, direct impact on your PhD work, because both the PhD and the illness are all encompassing by their very nature – there is no escaping this. You may also be far from home and family too, which will make this situation even tougher.

If you’re a PI (or in another position of leadership) and wondering how you can support an ECR through cancer or something else very difficult, one of the very best ways you can do this is by fostering an inclusive, supportive community in your lab and wider department. I am incredibly lucky – a lot of hard work had already gone into this long before I jointed the Microbiology Department here in Liverpool, and I have benefited from this enormously. To be clear: if not for this community, and the leaders within it with a holistic approach to mentorship and supervision, I doubt my PhD would have survived my diagnosis.

When and why did you first become interested in microbiology?

I’m a big reader – after devouring everything by Richard Dawkins and Jared Diamond during my commutes and lunch breaks, I somehow found my way to Martin J. Blaser’s Missing Microbes and Ed Yong’s I Contain Multitudes. This sparked the desire to return to education and pursue a degree in life sciences.

A short time later, during my time at college working towards this, I therefore made time to listen to a lecture by a guest speaker from the University of Liverpool – as fate would have it, this speaker would be one of my future PhD supervisors, Jay. Jay’s lecture helped me see beyond the pages of those popular science books, offering instead a glimpse into the actual day to day life and research priorities of microbiologists at the University of Liverpool. This led to an intern week in his lab that summer, at the end of which I knew I’d found my calling.

If you hadn’t gone into science, what career path do you think you would you have chosen?

I’m a bit unusual in that I had a career in politics, which I found very rewarding, prior to my undergraduate degree in Microbiology, which I obtained in my mid-30s. I’ve always wanted to be a scientist for as long as I can remember, but had to take a detour as my high school didn’t allow me to take STEM related A Levels. Refusing to give up on that ambition and pursuing it via a Foundation Year later in life was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made – I can’t imagine doing anything else, now.

Could you tell us why you decided to join the Society?

I was awarded a Society Undergraduate of the Year Award in 2019, which came with 12 months free membership – I’ve renewed it every year since. During my time as an undergraduate, I was strongly encouraged to join by early career researcher (ECR) members of the labs I worked in, as well as my supervisors. After they took the time to explain how much the Society did to support its members, for example through initiatives like travel grants, membership was a no brainer. Of course, I’m now one of those ECR members encouraging current undergraduates to sign up!

If you are interested in taking part in a Q&A for an awareness day, more details regarding how to get involved are available on our awareness days webpage.