On the Horizon: The spread of Lassa fever

Posted on July 21, 2016 by Anand Jagatia

On the Horizon is the Society’s blog series on emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. For this article, we spoke to Dr Lina Moses from Tulane University in New Orleans about Lassa fever, a viral infection spreading across parts of West Africa.

Lassa fever is thought to kill around 5,000 people across West Africa each year. The disease is caused by a virus, and usually begins with a mild fever along with weakness and headache. But in around a fifth of cases, symptoms are more serious, including vomiting, severe haemorrhaging (from the gums, eyes or nose), and death.

The early symptoms of Lassa fever are similar to many other diseases, like flu and malaria, which means that for many people, by the time they are diagnosed, it’s too late.

The ‘Lassa season’, which normally runs from November to February, is continuing for longer this year. Cases of Lassa fever are on the rise across West Africa, but Nigeria in particular is experiencing an especially deadly outbreak. According to the WHO, the country has seen over 270 reported cases and 149 deaths since August 2015.

Increased vigilance and better detection in the wake of the Ebola outbreak may partly be responsible for the increase in reported cases, but the death rate for the current outbreak seems to be much higher than the usual 1–15%. The reasons for this remain unclear.

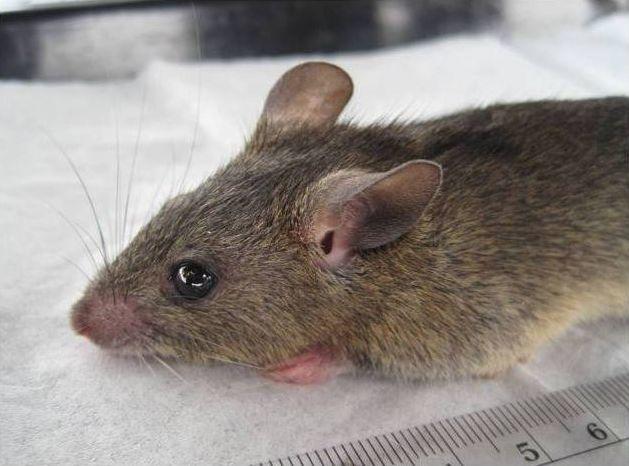

Lassa fever is spread by the multimammate rat (Mastomys natalensis). These rodents are extremely common in West Africa, breeding quickly and in large numbers. But exactly how people tend to interact with rats, and how the virus is most easily transmitted (through urine, faeces, blood, or eating rats that are sometimes caught for food) isn’t really known.

Dr Lina Moses is a researcher at Tulane University trying to understand what happens at the rodent–human interface in Sierra Leone, another country with endemic Lassa fever. Her work attempts to unravel the factors and behaviours that may prevent or enhance transmission of the disease.

“There isn’t really an age group or sex at higher risk [of contracting Lassa] that we’ve identified,” explains Lina. “We don’t know if it’s during agricultural practices or inside households that transmission occurs. Many of the men, women and children are subsistence farmers, so it’s hard to figure out where people are getting exposed.”

Lina has also been developing community interventions for rodent control in Sierra Leone. It’s not possible to rid the villages of rats completely, but the aim is to reduce populations enough to break the cycle of transmission to humans. The aim of the project is to see which methods are most effective at controlling rodents, and which get the most buy-in from locals.

“People like to trap rats. I think the main reason is that it’s mentally measurable to them, they can see that a rodent is being removed from their house,” Lina says. “But there’s some risk [of infection] there in terms of handling the rodents.”

One potential solution is to use local, disposable traps made from branches, leaves and twine, instead of Western traps made from plastic or metal. Local traps are cheap, sustainable and effective, and can be destroyed safely after use.

According to Lina’s research, people are less enthusiastic about preventative measures to keep rats away in the first place. This may be partly because such measures are perceived as less effective, or because continuous rodent control is simply low down on people’s priority lists.

“In Kenema district where we work, most people know that Lassa is a serious disease, and around half of them know that it’s spread by rats,” explains Lina. “But it’s all about priorities – sometimes getting food on the table is more important. And people have a lot of other health priorities, like malaria, which can be severe in small children,” says Lina.

The sheer number of rodents in the land around villages also means it’s extremely difficult to stop them from entering people’s homes – and the living conditions faced by most don’t help. “I sympathise, because even my house in New Orleans with access to proper storage, I’ll delay doing the dishes for example,” says Lina. “It’s challenging in Sierra Leone because they don’t have cabinets, and often can’t afford nice metal or plastic containers for food.”

As well as this, many villagers in Sierra Leone are rice farmers, and it’s common for people to store the entire day’s harvest inside their homes to prevent theft. But leaving this much rice indoors is almost guaranteed to attract rodents, and it’s difficult to find a drum or container large enough to store it.

“There are solutions that don’t require a whole lot of resources,” says Lina. “Some people build rice barns, which are essentially like houses but raised, with cones wrapped around the posts to stop rats climbing up.” Having a rice barn to store a harvest can be very effective. Ideally, several families could share a rice barn together and use it to store their rice harvest, but this requires both money and trust.

There is one other method of rodent control that’s particularly intriguing – cats. Lina says in one village that passed a law requiring every house to have a cat (and another prohibiting anyone from eating a cat, which does happen from time to time), the number of Mastomysrats fell dramatically. And since the laws were passed, there have been no more cases of Lassa transmission.

“Cats are very effective at reducing rodent populations, but we don’t know if Lassa virus can spread to cats or if cats can transmit Lassa to humans,” says Lina. “So unfortunately we didn’t look at cats in our interventions – although it might end up being the biggest thing.” (Interestingly, the WHO still recommends keeping a cat as a way to prevent infection).

At the moment, there is no vaccine for Lassa fever, although there are candidates waiting for clinical trials. But because the main route of transmission is from rats, and Lassa isn’t transmitted very efficiently between humans (unlike Ebola, for example), rodent control will always be a part of the solution, even if a successful vaccine is developed.

“Rodent vaccines could also be useful, if they were cheap,” says Lina. “But rodents have a shorter life expectancy and faster reproductive rates than humans, so that would have to be done regularly. If we want to reduce the burden of Lassa, we have to come at it from many different angles.”