Scratching the surface: how microbes adhere to worktops

Posted on June 5, 2017 by Anand Jagatia

Have you ever noticed when cleaning a sink or a saucepan that certain spots get tougher to clean over time, and the harder you scrub them, the worse it gets?

This sometimes happens when we clean things with abrasive products like scouring pads. In an effort to shift the stubborn stains or dirt, you scratch the surface you are cleaning and make it rougher. This in turn means that dirt gets lodged more easily in the scratches – so next time, you have to scrub even harder to get rid of them, and the cycle continues.

Professor Jo Verran is a microbiologist at Manchester Metropolitan University researching the science behind this kind of phenomenon – how microbes interact with surfaces and what that means for hygiene. Jo gave a talk on her work at our Annual Conference last month.

“A hygienic surface needs to be smooth, hard, inert and easy to clean,” she says. “Stainless steel is a good example of that – but stainless steel will scratch. So how does scratching or cleaning or scrubbing affect its clean-ability?”

Surfaces like stainless steel are used widely in places where hygiene is key, such as professional kitchens, food factories and hospitals, so studying how they retain microbes is important. This involves creating realistic models for surface wear, and how that affects any interaction with micro-organisms.

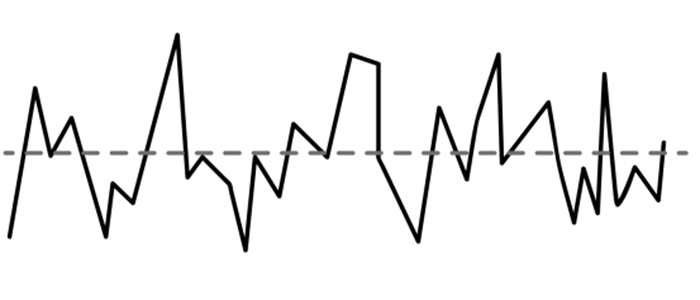

Initially, Jo’s group used a fairly simple way to quantify roughness. You take the profile of a surface along a cross-section, and measure how flat or bumpy it is. A totally smooth surface would give you a flat line, while a rough one would give you a series of ‘hills’ and ‘valleys’, like a landscape.

Taking the average distance of these peaks and troughs from the centre gives you a single number (Ra), that represents roughness. A rougher surface has more nooks and crannies where microbes can get lodged, so lower Ra values are considered more hygienic.

“We started asking questions – what about the type and degree of roughness? What about the size of the cells, the presence of organic material?” says Jo. “Does it matter if you have loads of bacteria that are easy to remove? Or is it worse not to have many bacteria but you can’t get them off?”

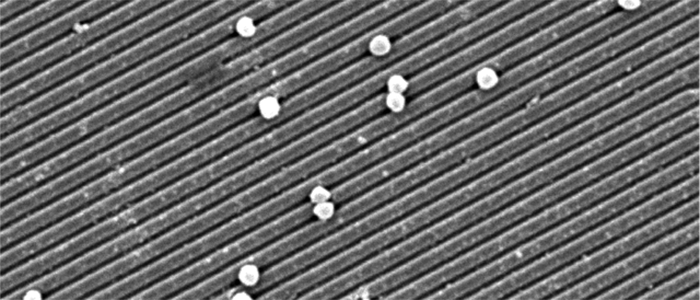

The group soon moved beyond Ra values. For one thing, it only tells you about roughness along a particular line. And because Ra is just an average, it also reveals nothing about the shapes or the properties of the features on the surface ‘landscape’. To study the effect of those, you need a 3D representation of the surface – which an atomic force microscope (AFM), provides.

“The AFM has a nano size probe, and it scans across the surface in a series of parallel lines,” Jo explains. “It goes up and down as the surface goes up and down, and the movement of the probe is captured by a laser, so you get an indirect image of the surface.”

The AFM allows you to look at surface features on a nanometre scale (billionths of a metre) rather than a micrometre scale (millionths of metre). Once the team began to look at surfaces in this way, it was possible to look at different kinds of roughness (pits or scratches, for example), and see whether they had an impact on microbial retention. But it also meant the team could start to mimic real world surface wear patterns in the laboratory.

“We were able to take the AFM into food factories, look at in situ surfaces, and get images,” she says. “Then, back in the lab, we would recreate the different types of surface topographies. This meant that we had lots of replicate ‘worn’ surfaces for further studies.”

The team also studied the attachment of microbes as well as their retention – so, not only how many cells ‘settled’ onto different surfaces, but how firmly they stayed there. By increasing the force of the AFM probe as it moved across the surface, they could measure how easy it was to remove individual cells.

By doing this kind of work, Jo’s team has been able to look in incredible detail at what makes some surfaces more hygienic than others, and what the best cleaning regimes are. They’ve also been able to test the properties of different coatings – for example, adding a titanium coating to stainless steel discouraged the retention of E. coli, and made it easier to remove.

“What we were trying to do was quantify, measure and visualise phenomena that everyone takes for granted,” Jo says. “We weren’t making massive advances in general understanding of scientific principles, but we were providing a more scientific underpinning for it. I think this is really important!”