Spotlight on Grants: A search for prions in yeast

Posted on October 13, 2016 by Alister Brown & Professor Mick Tuite

Each year, the Microbiology Society awards a number of grants that enable undergraduates to work on microbiological research projects during the summer vacation. Over the next few weeks, we’ll be posting a series of articles from students who were awarded Harry Smith Vacation Studentships this summer. This week is Alister Brown, a third-year Biomedical Science student at the University of Kent.

A search for prions in Saccharomyces yeast

FROM THE STUDENT: Alister Brown

Prions are a special class of protein that can exist in two forms: normal and misfolded. Misfolded prions can act as infectious agents and have been linked to brain diseases such as human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy).

Not all prions cause disease though, as is the case with yeasts, where several different prions have been described. My research in the Kent Fungal Group has focused on studying prions in different species of yeasts and how they affect the ‘infected’ host cells. While one yeast species, baker’s yeast or Saccharomyces cerevisiae, has been studied extensively regarding this and all manner of other topics, other species of Saccharomyces have received far less attention.

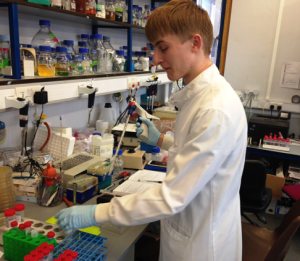

I set out to identify suspected prion proteins in three different Saccharomyces species, first by looking at amino acid sequences using a computer program called PAPA. This predicts ‘prion-domains’ in proteins that are typically rich in certain amino acids. From this point I aimed to investigate the effect that prions have on yeast, including the ability to utilise different carbon sources for energy, resistance to salt stress and to antibiotics. This was achieved by “prion-curing” the cells – chemically inhibiting the activity of proteins essential for spreading yeast prions from cell-to-cell.

Initially, another aim was to transform these strains with DNA that codes for prion proteins linked to green fluorescent protein. This allows you to visualise prion formation in a living cell. However, after several unsuccessful attempts at transforming these species, we decided to focus on investigating the phenotypic difference(s) caused by prions, as this had already shown promising results.

I found the Kent Fungal Group labs to be a great place to work, filled with friendly and supportive people who made my placement very enjoyable. The atmosphere in the lab provided a nice contrast to that of teaching labs, as I was allowed to work independently and trusted to make my own decisions. This truly made it feel like the work I did was my own and as such I am very proud of all I have achieved over the two months I have worked here. One of the most important things I have learnt is how to deal with mistakes and failures, and how to critically analyse how I can improve what I am doing.

Following my placement, the work I have been doing will be picked up by a PhD student who will be able to investigate the findings from my placement in much more depth and detail. I look forward to hearing more about how their work progresses in the future. My experiences have also helped me greatly in deciding my future career path as it has shown me how enjoyable and rewarding lab work can be, and I am very grateful to the Microbiology Society and Kent Fungal Group for giving me this opportunity.

FROM THE SUPERVISOR: Professor Mick Tuite

Our research group tries to take on a vacation student every summer, in part to carry out a small project we want doing, but also because we enjoy the challenge of inspiring students to become bench scientists. In Alister’s case, his project was building on our work with Saccharomyces cerevisiae prions but looking at other, albeit closely related, yeast species. In setting up the project Alister showed a keen interest in the prion concept and has now worked alongside experienced yeast prionologists, not least being our ‘Emeritus Postdoc’ Brian Cox who discovered one of the best studied yeast prions, [PSI+], in 1965!

Working in a research lab on your own project is definitely not the same as doing experiments in an undergraduate practical class. For a start, not all experiments work the first time you do them, so projects like this one are useful for introducing new students to problems and effective troubleshooting. The ability to quickly sort out technical issues is one of the most important skills for budding researchers like Alister to learn and is a key part of the learning curve of real science!

The study Alister is undertaking is important to us as it lays the groundwork for our new PhD student, who is starting in September and was a vacation student with us last summer. We very much hope Alister has been sufficiently inspired to pursue a PhD after he graduates next summer.

To find out more about the Harry Smith Vacation Studentships, please contact [email protected]