Surfer bums and antibiotic resistant bacteria

Posted on January 20, 2016 by Anand Jagatia

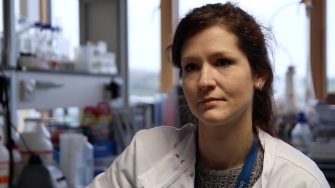

Are surfers at greater risk of being colonised by antibiotic resistant bacteria? Anne Leonard, a PhD student at the University of Exeter Medical School, is trying to find out. Anne is part of a research team led by Dr William Gaze studying antimicrobial resistance in the environment.

Antibiotics are routinely given to humans and animals to treat bacterial infections. Occasionally however, bacteria can evolve and become resistant to these drugs. Resistance is something that occurs naturally, but the overuse and misuse of antibiotics is accelerating the process, which is becoming a serious threat to human health.

Antibiotic resistant bacteria in the human gut can be excreted, finding their way into wastewater treatment plants before being washed into the sea. In addition, heavy rainfall can cause sewage and bacteria to be discharged into rivers and the sea, where they can come into contact with people.

As part of her PhD, Anne is looking at resistant bacteria in coastal waters, and the impact they may have on human health. Last year at the Society’s Annual Conference, the team presented research on the number of resistant E. coli bacteria swallowed by people doing water sports. The study estimated that 6.3 million water sport sessions in 2012 led to someone swallowing an antibiotic resistant strain of E. coli.

While many strains of E. coli are harmless or even beneficial to our health, some can cause disease, so exposure to resistant strains could cause infections that are difficult to treat. Surfers in particular swallow large amounts of seawater, around 170ml per session, which puts them at high risk of also swallowing resistant bacteria.

To understand how exposure to resistant bacteria might affect surfers, Anne is running a new study called the Beach Bum Survey. Working with the organisation Surfers Against Sewage, the team recruited regular surfers to sample their own gut bacteria using rectal swabs. Anne is now analysing their gut bacteria to see if they contain more resistant strains of E. coli than people who don’t spend time in the sea, and so shed some light on the impact of marine pollution on human health.