Towards a universal coronavirus vaccine: science fact or science-fiction?

Posted on April 1, 2015 by Nancy Mendoza

New research being presented today at the Annual Conference describes how the blood serum of people who have recovered from the SARS (serious acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus can neutralise the MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) coronavirus, which was recently discovered in Saudi Arabia.

Keith Grehan from the University of Kent’s Viral Pseudotype Unit has been researching the possibility of a vaccine that protects against multiple coronaviruses, which may ultimately prevent, or help control, future outbreaks of SARS, MERS, or whatever the next emerging coronavirus might be.

Coronaviruses cause many diseases, including SARS, MERS and even the common cold. Unlike colds, SARS and MERS are serious respiratory diseases; SARS caused an outbreak of severe pneumonia in China in 2002 in which almost one in ten of the 8098 reported cases were fatal.

MERS emerged in the Middle East in 2012 and while the outbreak continues, the rate of serious disease has been low. This could be because, having learned lessons from SARS, the public health response has been effective; it could be that MERS simply isn’t as infectious as SARS; or MERS may be very infectious but without causing disease in all cases.

SARS and MERS are betacoronaviruses – one of four types of coronavirus. They all originate in animals and in addition to SARS and MERS there are two more that have passed to humans: OC43 (one of the many common cold viruses) and HKU1 (an extremely rare pneumonia-causing virus).

As part of wider efforts to understand these viruses, Keith and his colleagues have been testing the potential for antibodies against SARS to also attack MERS, and the results have been positive.

These viruses can be dangerous to work with and require specialist research facilities. Without access to these, Keith and his colleagues had to find a creative way of studying MERS, which they did by using a ‘pseudotype virus’.

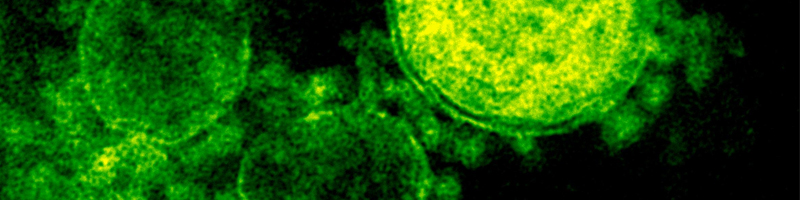

The pseudotype the team created used the inactive shell of an unrelated virus, but included a molecule normally found on the surface of the MERS virus. Known as the ‘spike protein’, this molecule binds to the surface of human cells, helping the virus to infect them. Inside the shell, the researchers included a gene that encodes a fluorescent protein, which enabled them to see when the pseudovirus had infected a cell.

“We found that our pseudotype virus was able to infect MERS susceptible cells called HuH-7 cells, so we knew we had a good model,” Keith said.

Keith incubated the MERS pseudotype virus with HuH-7 cells again, but this time added blood serum from people who had been infected with SARS. In some cases the serum did indeed prevent the virus from infecting cells.

Keith explained: “In previous studies involving the spike protein, researchers have focused on a part called the ‘receptor binding region’. This is very different in MERS, SARS and other betacoronaviruses. The human body produces antibodies against this part of the spike protein – a different one for each virus – which makes it a useful way to distinguish whether someone has MERS or SARS, or something else.”

By choosing to focus on another part of the spike protein of MERS – the S2 region – Keith and his colleagues were taking a slightly different approach.

Although the spike protein looks identical in MERS and SARS, the corresponding genetic sequence is, overall, quite different. But the part of the genetic sequence that encodes the S2 region is remarkably similar in these and other betacoronaviruses. Indeed, the S2 region might stimulate the production of antibodies that could cross-react with both SARS and MERS, which could explain Keith’s results.

Keith said, “Our results are not uniform so it’s too early to say that in all cases the SARS patients had antibodies that would be effective against MERS. We really need to do more studies, with serum from a much larger cohort of patients.

“And, of course, MERS and SARS are found in different parts of the world, so it’s unlikely that people who have recovered from SARS would have a chance to encounter MERS coronavirus in everyday life, but it’s possible they could be protected if they visited a region where MERS coronavirus is circulating.”

This research raises the possibility that the S2 region is a vaccine target that could be common to most, or all, of the betacoronaviruses.

“If we can confirm that humans do produce antibodies against the S2 region, there is a real possibility that a vaccine could work against all of the betacoronaviruses, including the OC43 virus, which causes colds,” Keith concluded.

Unfortunately the common cold is here to stay – OC43 is just one of a large number of cold viruses – but this could be good news for preventing SARS and MERS, and dealing with any future unknown betacoronavirus outbreak. Given that two of the most worrying disease outbreaks of the past ten years or so have been caused by previously unknown coronaviruses, such a vaccine could be an effective insurance policy for the health of everyone.

Nancy is a freelance science writer www.nancywmendoza.co.uk