Why won’t TB go away?

Posted on October 16, 2018 by Suzanne Martin

This September, the United Nations convened a high-level meeting aimed at addressing the global tuberculosis (TB) epidemic. Delegates heard from heads of state and political leaders, but one of the most powerful speakers was Nandita Venkatesan. Shortly after graduating from university in 2007, Nandita was diagnosed with TB. At the high-level meeting, she spoke of her years spent battling the disease and the devastation she felt when she lost her hearing as a side effect of the essential, lifesaving treatments she had to take.

What is TB?

Tuberculosis is caused by the bacterium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The most important form of the disease is pulmonary TB, which affects the lungs, but multiple organs can be affected. The bacterium is inherently resistant to the body’s immune defences, because of its ability to hide in immune cells.

Despite being curable with antibiotics, each year TB kills more people than malaria and HIV combined. Most cases occur in Africa and Asia, but all countries are affected including the UK.

If TB is curable, why does it still affect so many people?

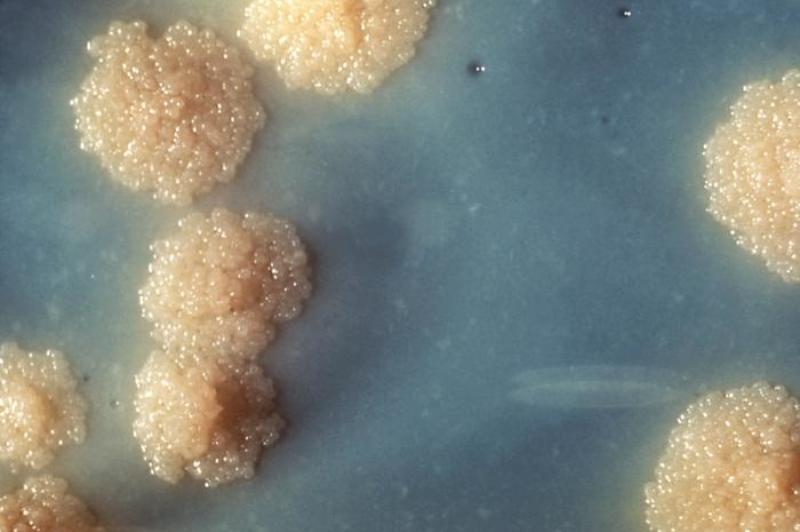

Standard methods for diagnosing TB include sputum microscopy, which involves using a microscope to detect Mycobacteria in fluid collected from the lower airways after a patient coughs deeply. The organism can also be detected by culturing it from patient derived samples. Both methods are insensitive and therefore do not reliably identify all cases. In addition, Mycobacteria grow very slowly in culture and so there are often long delays before patients are diagnosed and treated.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis cultures

Newer, more sensitive diagnostic tests are also available. These amplify Mycobacteria DNA in patient samples and predict antibiotic sensitivity within hours, instead of days. However, in many impoverished communities, access to diagnostic tests is limited. It is estimated that each year around 3 million people with TB are undiagnosed. Furthermore, because antibiotic sensitivity testing is inadequately carried out, ineffective treatments are often prescribed. This prolongs patient suffering and enables the generation of antibiotic resistance.

Tuberculosis accounts for 1/3 of global antibiotic resistant infections

Initial treatment courses for TB last 6 months and involve taking a combination of different drugs. For many people, adhering to such lengthy regimens can be extremely difficult. In developing countries, clinics might be spread across large distances and for those struggling with poverty, the need to attend clinics to receive treatment is often outweighed by the requirement to earn a living. This results in patients taking irregular doses or failing to complete the full treatment course, both of which are drivers towards antibiotic resistance. Side effects are also relatively common and medical staff are often too stretched to support patients in dealing with these. Nandita lamented that she’d had no prior warning of the potential to lose her hearing before it happened, and this made it even harder to cope.

Once someone develops antibiotic resistant tuberculosis, the chances of achieving a cure plummet to 54% from 85% for those with drug susceptible disease. The treatment courses required are also even more gruelling and can take several years.

Preventing TB is difficult without a good vaccine

Tuberculosis is spread in infectious droplets propelled into the air by coughing. The only available vaccine is the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine which was first introduced in 1921. The vaccine provides good protection against multi-organ and pulmonary forms of the disease in young children. However, when given to adults, protection against pulmonary disease is unreliable.

Living with TB

The personal consequences of living with TB can be devastating. In addition to its physical manifestations, the disease also has a huge emotional impact. Sufferers are often stigmatised within their communities because TB is seen as a curse, and those affected can feel isolated and abandoned by their families.

Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty, affecting the poorest communities around the world. World Health Organisation members have pledged to end the global TB epidemic by 2030. At the current rate of decline this target will not be achieved and this is due to an estimated $1.3 billion/ year funding gap. Addressing the United Nations high-level meeting, Nandita Venkatesan was resolute:

People affected by TB have a burning desire to shake the status quo. Esteemed leaders, I can’t hear you today, but I’ll make sure you hear me – loud & clear

The UN’s response was to pledge to find and treat 40 million people with TB by 2022 and to release global funds of $13 billion to improve access to universal healthcare and a further $2 billion for research initiatives to develop better diagnostics, shorter treatment regimens and an effective vaccine. Could this be the new hope that the 10 million people living with TB have been desperately waiting for? Let’s hope so.

Further reading:

Has TB had its time?

"A curse from the gods": India's tuberculosis crisis

Tuberculosis took away 22kg and most of her hearing, but Nandita continues to dance to the music of life

Global tuberculosis report 2018