World Polio Day 2015

Posted on October 23, 2015 by Anand Jagatia

24 October is World Polio Day. The day was established by Rotary International over ten years ago, to mark the birth of Jonas Salk, who developed the first effective polio vaccine with his team in 1952. Since then, we have almost completely eliminated polio worldwide – but the virus remains endemic to some countries, meaning people everywhere are still at risk.

Polio (short for poliomyelitis) is caused by the poliovirus. The disease is often referred to as infantile paralysis, as it mainly affects children under five and can cause irreversible paralysis if the virus spreads to the nervous system. The word poliomyelitis comes from the Greek ‘polio’ (grey) and ‘myelos’ (marrow, referring to the spinal cord).

Symptoms and transmission

Polio is highly infectious and is transmitted by the faecal-oral route. This includes contact with the faeces of an infected person, but also with water or food that has been contaminated, either directly or by flies. Poor sanitation greatly increases the risk of infection.

Most polio infections are asymptomatic, but infected people can still spread the virus to others. Symptoms develop in around a quarter of cases, and include fever, tiredness, headache, vomiting, stiffness in the neck and pain in the limbs. Around 0.5% of cases lead to permanent paralysis, and around one in ten paralysed patients die when the virus attacks the neurons of the brainstem, ultimately causing the respiratory muscles to stop working.

Post-polio syndrome (PPS) is a complication where symptoms return many years after the person has recovered. There is no cure, but the condition can be managed. It is still unclear exactly what causes PPS – current theories suggest that nerves in the spinal cord slowly deteriorate after the initial infection, leading to muscle pain, weakness and fatigue. We do know that PPS is not caused by poliovirus remaining dormant in the body, which means that the syndrome isn’t contagious like polio is.

Vaccines

There is no cure for polio, but it is entirely preventable with a vaccine that is given multiple times. There are two kinds of vaccine: inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which is made from poliovirus killed with formalin, and oral polio vaccine (OPV), which is made from live but weakened poliovirus strains. Both of these give lifelong protection against polio.

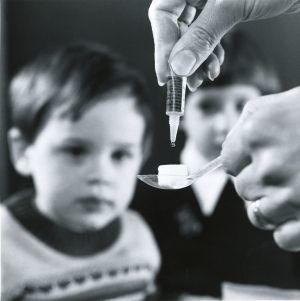

OPV is cheap to produce and suited for mass vaccination campaigns because it is delivered orally (drops of the vaccine used to be added to sugar cubes and given to children to eat). However, because the virus is still in (an attenuated) live form, in extremely rare cases it can mutate into a more dangerous strain that causes paralysis, known as circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV).

cVDPV occurs when not enough people in a population are immunised against the disease. In these cases, the attenuated virus remains in circulation, because it continues to replicate inside people who haven’t been vaccinated and spreads to others. The longer this strain is in circulation, the greater the chance that it will mutate and cause paralysis.

In September 2015, three new cases of cVDPV were confirmed in Ukraine and Mali – countries which were previously polio-free, but have low rates of immunisation. cVDPV should not scare people from being vaccinated, as under-immunisation is precisely what leads to it in the first place. Out of the 10 billion doses of OPV that have been administered since 2000, only 24 outbreaks of cVDPV have occurred. The way to prevent (and deal with) outbreaks is make sure everyone in a population is vaccinated.

Outlook

Global efforts to eliminate polio have resulted in a 99% decrease in the number of cases since 1998. We are closer than ever to a world completely free from polio. Just last month, the World Health Organization announced that the disease is no longer endemic to Nigeria, which has gone more than a year without any cases of reported wild poliovirus. Nigeria was the last country in Africa to eradicate polio and if it stays this way for three years, Africa as a continent will be designated polio-free.

Polio now remains endemic to only two countries: Afghanistan and Pakistan. Until virus transmission is interrupted in these countries, all other countries remain at risk, especially those with poor public health services. Vaccination campaigns are key to preventing future outbreaks, which means public trust in immunisation must be fought for, and maintained, if we are to finally rid the world of polio.