New species discovered in human gut is an important step towards understanding the interaction between humans and the microbiome

17 April 2025

An international team of microbiologists from the Medical University of Graz, Austria, the DSMZ—German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany, and the University of Illinois, USA, has identified and described a previously unknown species of methane-producing archaea in the human gut: Methanobrevibacter intestini sp. nov. (strain WWM1085). In addition, a new variant of the species Methanobrevibacter smithii, which is referred to as GRAZ-2, was isolated. The scientists thus took another important step towards understanding the interaction between humans and the microbiome.

Unknown original inhabitants of the gut: what is special about archaea?

Archaea are a distinct domain of life — along with bacteria and eukaryotes (i.e., organisms with a cell nucleus such as animals, plants and fungi). Although they appear similar to bacteria under the microscope, they differ in many basic aspects: for example, their cell membrane, metabolic pathways and genetic characteristics. Archaea were originally discovered above all in extreme environments such as hot springs or salt lakes, but in the meantime, it is clear: they are also found in the human body, especially in the gut.

Methane-producing archaea, so-called methanogens, are a particularly exciting research area: they produce methane from simple substrates such as hydrogen and CO₂ and thus significantly contribute to microbial metabolic processes — in ruminants, for example, but also in the human gut. Their research is still in its infancy because they are extremely sensitive to oxygen and difficult to cultivate.

New discovery sheds light on the forgotten world of the gut microbiome

"Our discovery is a further piece in the puzzle towards understanding how the human microbiome functions," explains Christine Moissl-Eichinger, Professor of Interactive Microbiome Research at the Medical University of Graz. While microbiome research focuses on bacteria, archaea have eked out a shadowy existence — in spite of their potentially great influence on key metabolic processes in the human body. "Archaea have long been overlooked," says Christine Moissl-Eichinger. "They may play a significant role in gut function, microbial gas metabolism and possibly even the development or progression of certain diseases."

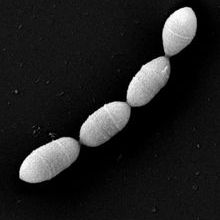

Through a combination of the latest methods — including specific anaerobic cultivation, high-resolution electron microscopy and comprehensive DNA sequencing — the Graz research team was able to isolate two special representatives of this group of microorganisms from the human gut:

The new species Methanobrevibacter intestini WWM1085 clearly differs genetically and physiologically from all previously known species. It thrives exclusively under strictly anaerobic conditions, produces methane, and surprisingly large amounts of succinic acid — a metabolic product that is associated with inflammatory processes in the human body.

The second strain that was discovered, a variant of Methanobrevibacter smithii referred to as GRAZ-2, exhibits unusual features: it produces formic acid, a molecule that may interfere with the metabolism of other gut inhabitants.

Both discoveries clearly indicate that the world of the archaea in the human gut is more complex and more relevant than previously assumed and has enormous potential for further research on health and disease.

The archaeome in focus: new avenues for microbiome medicine

The current study significantly contributes to a better understanding of the so-called "archaeome" — the totality of archaea that shape the human microbiome. This rarely explored area of the gut flora could provide important indications of previously overlooked connections between microbes and health.

It appears that only through the specific isolation and cultivation of such microorganisms can their characteristics and potential active mechanisms be investigated in detail. "We can only conduct specific mechanistic investigations with cultivated strains," stresses Viktoria Weinberger, the first author of the study. "This is essential in order to better understand the role of individual microorganisms in health and disease and in the long term to develop therapeutic approaches as well."

The discovery of Methanobrevibacter intestini and GRAZ-2 opens up a new chapter in archaea research as well as new perspectives for personalized microbiome medicine in the future.

NOTES FOR EDITORS

The paper 'Expanding the cultivable human archaeome: Methanobrevibacter intestini sp. nov. and strain Methanobrevibacter smithii ‘GRAZ-2’ from human faeces' by Viktoria Weinberger, Rokhsareh Mohammadzadeh, Marcus Blohs, Kerstin Kalt, Alexander Mahnert, Sarah Moser, Marina Cecovini, Polona Mertelj, Tamara Zurabishvili, Bhawna Arora, Jacqueline Wolf, Tejus Shinde, Tobias Madl, Hansjörg Habisch, Dagmar Kolb, Dominique Pernitsch, Kerstin Hingerl, William Metcalf and Christine Moissl-Eichinger is avalible in International Jouranl of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology at the following:

DOI: 10.1099/ijsem.0.006751

URL: https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/ijsem/10.1099/ijsem.0.006751

For further information contact

Viktoria Weinberger

Diagnostic and Research Institute of Hygiene, Microbiology and Environmental Medicine

Medical University of Graz

Tel.: +43 316 385 73774

Image: Medical University of Graz.