Can oil-eating bacteria clean up our seas?

25 February 2020

Oil spills have the potential to cause huge environmental damage. Naturally occurring hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria play an important role in breaking down oil in the event of a spill. Since the mid-1990s a number of these bacteria have been isolated, such as Alcanivorax and Marinobacter. Dr Tatyana Chernikova, Research Officer at Bangor University in Wales, has been investigating the hydrocarbon-degrading properties of some marine bacteria.

Some of the most important organisms on the earth are microscopic algae; these organisms live in both freshwater and marine ecosystems and produce approximately half of the earth’s oxygen via photosynthesis. They are also known to produce compounds that have a strong affinity for oils – known as oleophilic – such as long-chain fatty acids and alcohols. These algae have been reported to host bacteria that can break down these complex hydrocarbons. However, Dr Chernikova said; “little is known about the taxa of microalgae that can host such bacteria, composition of microalgae-associated microbial consortia and the responses of these consortia to the petroleum.”

The bacteria hosted by the algae create complex communities, however very few of these microbial communities have been studied, so Dr Chernikova studied the communities of two well-known species of microalgae that are found globally. Both microalgae contained similar microbial communities, which went through stark changes on the addition of petroleum. Without petroleum, genera known to degrade hydrocarbons, such as Alcanivorax and Marinobacter, only made up 0.5% of the microbial communities studied. However, on the addition of petroleum, these genera went through a huge increase, making up 80-90% of the total microbial population.

Dr Chernikova is optimistic about the two microalgae species. “Our study provides the strong experimental evidence for linking these microalgae with hydrocarbon-degrading specialist bacteria, such as Alcanivorax and Marinobacter and explains their ubiquity in marine environments,” she said

In the last few decades there have been many significant oil spills, most notably Exxon Valdez in 1989, the Prestige in 2002 and Deepwater Horizon, the largest oil spill disaster in history, where 168 million gallons of oil was released into the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. When oil spills occur, they have the potential to cause untold environmental and ecological damage. There are several ways to deal with oil spills, which can range from physical barriers to stop the spread, to chemical dispersants that speed up the breakdown of the oil. While these and other solutions have the potential to work, they have drawbacks; difficult conditions like rough seas or high winds can break barriers, and many of the chemicals used can cause their own problems; for example, the mix of broken-down crude oil and dispersants have been reported to be more harmful than crude oil to organisms like corals.

While the breakdown of oil by micro-organisms seems like the perfect solution, it can take a long time. Dr Chernikova is hoping to assess this in the next phase of the research. “Our future experimental work will need to answer some important questions about the efficiency of degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons by these microalgae-based bacterial consortia,” she said.

Dr Tatyana Chernikova will present her research as part of the Marine microbiology session at the Microbiology Society’s Annual Conference in Edinburgh this year. Her poster, titled ‘Hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms associated with photobioreactors-grown microalgae Pavlova lutheri and Nannochloropsis oculata’ will be available to view on Tuesday 31 March and Wednesday 1 April, with presentations taking place on Tuesday evening between 18:30–20:00.

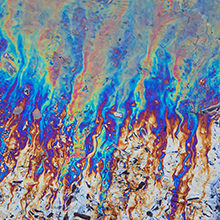

Image: iStock/mycteria.