Outreach: Microbiology at the Nottingham Festival of Science and Curiosity

Issue: Microbes and Food

07 August 2018 article

The 2018 Nottingham Festival of Science and Curiosity was a week-long programme, aiming to bring exciting and inspirational science, technology, engineering and maths to the general public. There were around 3,000 interactions with members of the public during the week. Of those attending, 41% were children aged 11 or younger, and 68% of people went along with their family to take part in the fun.

As part of the MRC/EPSRC-funded Nottingham Molecular Pathology Node at the University of Nottingham, with diverse interests in medicine, we displayed our science on five creative stalls at the ‘Science in the Shopping Centre’ event on Saturday 17 February, in partnership with Rick Hall of Ignite!, a science communication charity. Our research group, being mostly microbiologists, came up with an idea to show the public some interesting examples of ‘the microbes on and around us’, to demonstrate that there are infectious organisms in all sorts of places. Together with Dr Kazuyo Kaneko from the group, we manned the stall and chatted with visitors on the day. Our idea to show the public what microbial colonies look like on agar plates was extremely popular, as most had never had an opportunity to see this before (other than in photos) and they found it really fascinating.

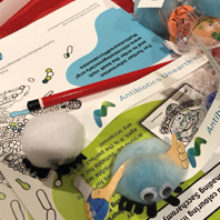

We swabbed some commonly used items (toilet door handles, kitchen surfaces, mobile phone, shoes etc.) and applied fingertips and coins to the surface of blood agar plates. After incubation, we sealed the plates into sturdy clear autoclave bags, and securely fixed them to our display table at the event. We invited visitors to guess which plates had been grown from swabs of the gents or ladies toilets, the floor, worktop or bin in our tea room, and to look at how many colonies had grown from the other items. Apologies if this appears sexist but we recovered more colonies from the gents’ toilet door handle than the ladies’. We were all horrified though to discover that the plate with the most colonies was inoculated from the worktop in our tea room, rather than the floor or the bin. Most likely due to a pretty ancient dish cloth. The visitors were amazed to find out that coins are made from metals, which kill bacteria, and to see that the colonies grown from fingertips resembled those recovered from the mobile phone. With help from the Microbiology Society, we had some educational leaflets and comics on handwashing and antibiotics, as well as pens, fluffy bugs, badges and stickers to give away. These all disappeared very swiftly, along with huge buckets of sweets and springy ‘bug’ toys.

Over 280 people came to visit our stall, from all walks of life, from pensioners to young children and everything in between. We were pleasantly surprised to find many people already understood that not all bacteria are ‘bad’ bacteria and that the overuse of antibiotics is a big problem – this is perhaps a reflection of how well the Public Health England antimicrobial resistance (AMR) campaigns have worked. We were even more surprised when a young girl of around 10 years old knew what an agar plate was – maybe a future microbiologist in the making? On the whole people were very interested and asked questions on lots of topics, from how we had grown the bacteria to effects of the microbiome. We even had a teacher taking notes and photographs to show her class. It was exciting for us to see so many members of the general public interested in bacteria and microbiology in general.

It was a very rewarding experience to be able to speak to the general public about our work and to receive such positive responses. It emphasises why we do research when we see people outside of the science-sphere engaging with microbiology and being genuinely curious about it all. As an early career microbiologist, engaging with the public is very important. Often we get so used to using our scientific jargon that trying to explain our science in more basic layman’s terms can be a real challenge, especially when talking to young children. To be able to explain your science to kids in a way that is simple enough for them to understand, but interesting enough to keep them engaged, is an art in itself.

Getting involved in public engagement at the beginning of your microbiology career gives you plenty of opportunities to improve these key communication skills. It is so important for the science community to engage with the public; from keeping them informed, to inspiring children to pursue a career in science, the benefits are huge. But the personal benefits are also really important. These include learning new skills and gaining confidence, but there is also a reminder that even the most simple things in microbiology can be truly fascinating.

Further information

Nottingham Festival of Science & Curiosity website

Microbiology Society resources

Nikki Osborne

PhD student from the Wellcome Trust Doctoral Training Programme in Antimicrobials and Antimicrobial Resistance, Centre for Biomolecular Sciences, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD

Karen Robinson

Associate Professor in Infections and Immunity, Centre for Biomolecular Sciences, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD

Images: Flyers for the Multicoloured Microbiomes colouring book and Antibiotics Unearthed bugs from the Society. K. Robinson.

The plates, quiz sheets, prizes and Microbiology Society resources on the stand. K. Robinson.

Coins applied to a blood agar plate, prior to incubation. K. Robinson.

Kazuyo Kaneko and Nikki Osborne ready to receive visitors to the stand. K. Robinson.