Editorial

Issue: Zoonotic diseases

05 November 2015 article

In our February edition of Microbiology Today, the Comment article focused on a story that has dominated our headlines: the Ebola pandemic that swept through West Africa and migrated onto European shores. It illustrates that infectious diseases are a clear and ever present danger that demand vigilance and a worldwide response, and can have catastrophic effects on societies. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) has also received media attention, and it is interesting that this disease started to hit the headlines as it emerged out of the Middle East to cause cases of infection in 26 countries including parts of the European Union.

Many emerging diseases that are causing concern with the public and healthcare communities are zoonotic diseases, but they are not a 21st century phenomenon. The World Health Organization describes rabies as a vaccine-preventable, ‘neglected disease of poor and vulnerable populations whose deaths are rarely reported’, and it continues to cause tens of thousands of deaths every year. Rabies has circulated for centuries. Jo Halliday, Katie Hampson and Tiziana Lembo touch on this in a thought-provoking article that describes the problems of endemic zoonoses that have the greatest impacts in developing countries, but get limited recognition. Their eradication could significantly improve health and livelihoods in some countries.

Hanna Jerome, Sreenu B. Vattipally and Emma C. Thomson begin their informative article in the 19th century with Louis Pasteur, who noticed that rabies was caused by an agent that could not be visualised using a light microscope. The authors describe how the toolkit for identification of zoonotic viruses has evolved substantially over the last century, leading to the current scenario where we may be able to predict which viruses might cross the species barrier to present a significant risk to the human population.

John Fazakerley describes chikungunya, a disease that has emerged recently from the forests of Africa to start its global journey, out across the islands of the Indian Ocean to India and South-east Asia, China and the Americas. The alphavirus – a small, enveloped, positive-sense RNA virus – first emerged to prominence early in 2005, causing severe joint pain and general discomfort. The virus is transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, which are now widely spread around the world.

Agnieszka Szemiel discusses another virus that has recently hit the headlines, hantaviruses, which are the only bunyaviruses that are direct zoonoses. The virus is maintained in the environment by persistent infections of rodents and causes little damage to its vector. It is transmitted to humans via aerosolised rodent urine, faeces, saliva, and occasionally by bite. Infection in humans can be fatal.

Helen Brown and Arnoud van Vliet’s article highlights that it is not just viruses that cause zoonotic diseases. Although Campylobacter was, arguably, the least known of the common bacterial food pathogens and very rarely made the headlines, the number of Campylobacter cases has remained relatively steady over the last few decades (an annual incidence of ~280,000 UK cases). In the past year public awareness of Campylobacter has been raised significantly, mainly due to the Food Standards Agency publishing data on the percentage of Campylobacter-positive meat samples from retail (64–79% of chicken meat was positive) putting pressure on the poultry sector and retailers to address the problem.

Zoonotic diseases are a global problem affecting both rich and poor countries. Professor Eric Fèvre has written a Comment piece describing the significant differences between a continent like Africa and one like Europe; namely the ability of national and regional systems to detect and respond to zoonotic disease threats. A common theme that has emerged from the articles is the economic burden that zoonotic diseases place on society, with the impact generally felt most keenly by the vulnerable and the poor. The articles also highlight that science offers solutions. We continue to develop vaccines, improve prevention, increase surveillance and adapt detection methodologies to sophisticate information. As mankind continues its impact on earth and its interactions, new zoonotic diseases will emerge. Maybe we are more ready now than we have ever been to meet these challenges?

LAURA BOWATER

Editor

[email protected]

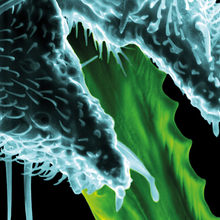

Image: Coloured scanning electron micrograph of the proboscis of an Anopheles gambiae mosquito. Science Photo Library..