Hantaviruses – neglected zoonoses

Issue: Zoonotic diseases

05 November 2015 article

Zoonotic diseases are defined as infections that are transmitted from vertebrate animal sources to humans, sometimes by way of an arthropod vector. Approximately 60% of infectious human pathogens are zoonotic. These diseases can be caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi and other parasitic organisms.

The most commonly mentioned zoonotic viruses are influenza, rabies, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and more recently, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and Ebola. However, there are many other emerging viral zoonoses, some of which belong to the largest RNA virus family, the Bunyaviridae, comprising over 350 known isolates. The family is classified into five genera, Orthobunyavirus, Nairovirus, Phlebovirus, Hantavirus and Tospovirus. The first three are maintained in nature by a propagative cycle involving blood-feeding arthropods (such as mosquitoes, ticks, midges) and susceptible warm-blooded vertebrate species, and include a number of human and animal pathogens such as La Crosse virus, Oropouche virus, Schmallenberg virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Rift Valley fever virus. The fifth genus, the tospoviruses, are important plant pathogens.

Hantaviruses are the only bunyaviruses that are direct zoonoses. They are maintained in the environment as persistent infections of rodents (voles, field mice, rats), which cause little damage to their rodent vector. They are transmitted to humans via aerosolised rodent urine, faeces, saliva, and occasionally by bite. Infection in humans can be fatal. Based on symptoms, hantaviruses are classified into two groups: the Eurasian Old World hantaviruses, which cause haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and are associated with approximately 0.1–15% fatality; and the New World hantaviruses with almost 40% fatality, causing Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) in the Americas.

A brief history

Although formally described half a century ago, history suggests that hantaviruses have been around for much longer. A disease with symptoms resembling HFRS was mentioned in a Chinese medical book dating back as early as 960 AD. Although there is no direct evidence, English sweating sickness, a mysterious illness that struck England in the 15th century, is consistent with a hantavirus infection. There were five major epidemics of sweating sickness in England recorded between 1485 and 1551. The disease must have already been known earlier, as Lord Stanley, an influential Welsh Lord, used sweating sickness as an excuse to withdraw from the Battle of Bosworth Field in the Wars of the Roses in 1485. The outbreaks occurred during summer months, preceded by harsh winters and periods of prolonged rainfall, which probably resulted in spikes in the numbers of small insectivore mammals. This is consistent with current observations of hantavirus epidemics, which coincide with fluctuations in rodent populations. Looking back at the English sweat, Seoul hantavirus and its vector, the black rat (Rattus rattus), a common rodent in Europe, could have been the culprit.

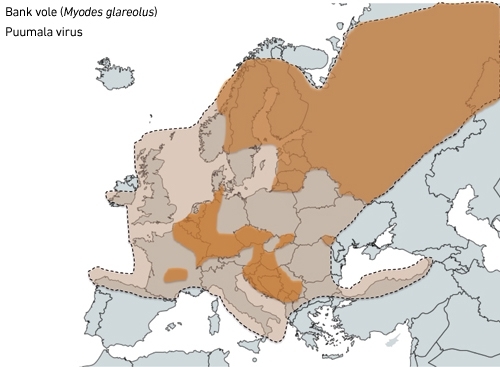

In 1718, another similar, but less lethal, infection was recorded in France and, later on, around Europe. It was named 'Picardy sweat' after the region where it first occurred. It was also referred to as military fever. Outbreaks mainly occurred in rural areas, and were subsequently linked to fluctuations in field rodent populations. Some scientists suggest that Picardy sweat could have been caused by Puumala virus or similar, which still occurs in these regions.

Hantavirus disease was also suggested to be the causative agent of many cases of epidemic nephritis during the American Civil War and World War I. The first clinical descriptions of HFRS can be found in hospital records from 1913 in eastern Russia and in 1932 the disease was linked to exposure to rodents. During World War II outbreaks of nephritis among German troops on the Eastern front and in Finland, where hantaviruses are endemic, were classified as rodent-borne. During the Korean War in the summer of 1951, an outbreak of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome struck United Nations troops. Later the pathogen was identified as a virus and named Hantaan after the river where the wild rats harbouring the virus had been captured. In the 1980s, based on the genome analyses, the group of viruses causing HFRS were assigned to the Bunyaviridae family as the Hantavirus genus. In the summer of 1993 the first cases of HCPS were recorded in the Four Corners region of the USA. The disease was caused by a new hantavirus later called Sin Nombre virus, which was spread by deer mice.

Hantaviruses in the UK

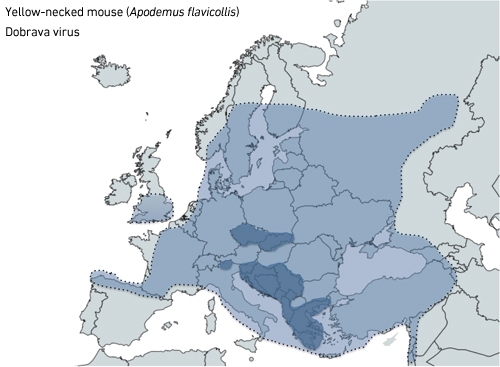

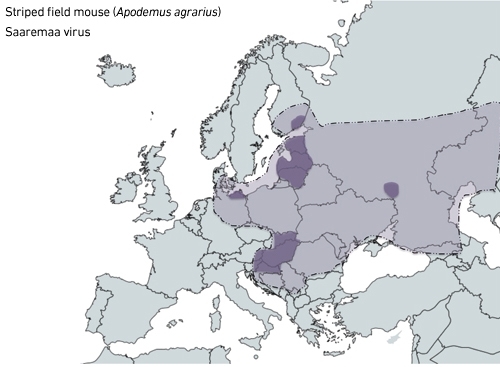

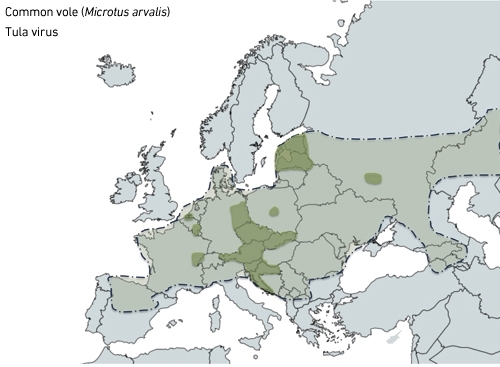

Several hantaviruses circulate in Europe: Seoul (carried by rats), Puumala (bank vole), Tula (common vole), Saaremaa and Dobrava (both in wild mice).

Hantaviruses very rarely appear in the news headlines in the UK. Also, when we look at distribution maps of hantaviruses in Europe, the UK is one of the few countries with little or no epidemiological data. General consensus is that HFRS is under-diagnosed in the UK, as, unless the patient develops kidney failure, the disease demonstrates as flu-like symptoms, and may easily pass unnoticed. Recent studies by Public Health England showed that, although they don't pose a major threat, hantaviruses are widely spread in the UK. Sero-surveillance studies showed that over 30% of pet rat owners had antibodies against hantaviruses, suggesting previous infection. In the case of occupationally exposed people like farmers, sewage and waste disposal workers, veterinarians, pest control, forestry and nature conservation workers, only 1–3% were sero-positive, which was similar to the numbers obtained for the general public. There are no extensive studies on the percentages of pets and wild rodents persistently infected with hantaviruses. Though whenever human cases of HFRS are diagnosed, animals in the surrounding environment test positive. In the last 4 years there were a few pet rat acquired cases of Seoul hantavirus which had to be hospitalised in North Wales, Yorkshire, Humberside and Scotland. On the other hand, studies of rodents trapped in the Tattenhall area, in Cheshire, showed the existence of a novel hantavirus, which is related to Puumala and Tula hantaviruses, which was previously not detected in the UK. Interestingly, rodents from the Arvicolinae family, that spread Puumala and Tula hantaviruses, are also found across mainland UK and Ireland. Looking at distribution maps of rodents that are known hantavirus vectors, it is striking that there have been so few confirmed hantavirus cases in the UK.

LIGHT-COLOURED AREAS INDICATE DISTRIBUTION OF THE RODENT HOST SPECIES,AND THE DARKER COLOURED AREAS SHOW WHERE APPROPRIATE VIRUS HAS BEEN FOUND. AREAS NOT FILLED INDICATE THAT THERE IS EITHER NO DATA AVAILABLE OR NEITHER HOST NOR VIRUS IS PRESENT.

Future outlook

Although hantaviruses don't pose an immediate threat to the UK, rodent surveillance studies should be carried out on a regular basis. Some viruses, including hantaviruses, can spread to new areas, including the UK, and are associated with climate and environmental changes. With a growing human population and increasing urbanisation, natural habitats of indigenous rodents are disrupted, which causes changes in behaviour and animal migration. Change in land use may lead to the emergence of viruses previously not known or not common in certain environments. Such changes may also put pressure on pathogen evolution, which could result in increased pathogenicity or even switching to a different vector.

In most cases European hantavirus infections result in a mild form of the disease. However, with easy access to cheap international travel, there is a risk of importing more dangerous hantaviruses and other pathogens into the UK. For example, last year a rare case of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS), caused by Choclo virus, was diagnosed in a UK resident who returned from Panama. Similarly, pathogens could be imported with exotic pets.

Currently there are no vaccines or antivirals available to combat hantaviruses, as the molecular biology of hantaviruses in not very well studied. Advances in diagnostics can lead to the discovery of novel viruses, but it also allows for the detection of previously mis- or under-diagnosed pathogens. Hantaviruses are just one example of emerging diseases that present an increasing threat to human health. Like the hantaviruses, there are many other zoonoses lurking around that are worth studying or still await discovery. In our rapidly changing world it is evermore important to keep up surveillance.

AGNIESZKA SZEMIEL

Medical Research Council – University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, Glasgow G61 1QH, UK

[email protected]

FURTHER READING

Heyman, P., Simons, L. & Cochez, C. (2014). Were the English sweating sickness and the Picardy sweat caused by hantaviruses? Viruses 6, 151–171.

Olsson, G. E., Leirs, H. & Henttonen, H. (2010). Hantaviruses and their hosts in

Europe: reservoirs here and there, but not everywhere? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 10, 549–561.

Public Health England (2014). Hantavirus infection in people: sero-surveillance study in England. http://microb.io/1MR4xPJ. Last accessed 25 August 2015.

Vaheri, A. & others (2013). Hantavirus infections in Europe and their impact on public health. Rev Med Virol 23, 35–49.

Image: Bank vole. Peter Trimming. Pet rat. Artur Malinowski. Geographical distribution of European hantaviruses and their vectors. Adapted from Olsson et al. (2010)..