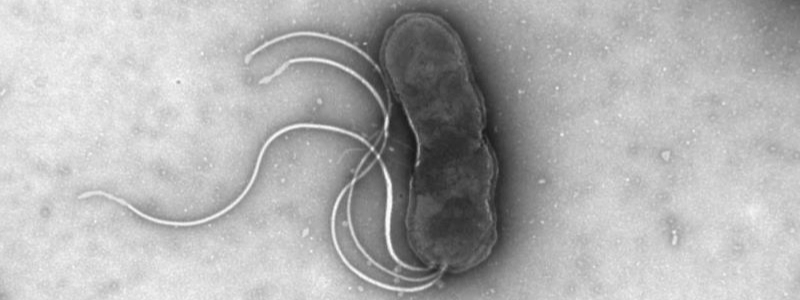

A New Sheriff in Nottingham: Helicobacter pylori

Posted on January 8, 2024 by Farah Mahmood, Elizabeth Garvey, Suffi Suffian and Joanne Rhead

Farah Mahmood, Elizabeth Garvey, Suffi Suffian and Joanne Rhead take us behind the scenes of their latest publication 'High incidence of antibiotic resistance amongst isolates of Helicobacter pylori collected in Nottingham, UK, between 2001 and 2018' published in Journal of Medical Microbiology.

We (Farah Mahmood, Elizabeth Garvey, Suffi Suffian, and Joanne Rhead) are members of Professor Karen Robinson’s research group, based at the Biodiscovery Institute in the University of Nottingham, UK.

Our research revolves around one bacterium – Helicobacter pylori. It infects around half of the world’s population, yet treatment for it is becoming less effective due to increasing levels of antimicrobial resistance. Ineffective H. pylori eradication can have serious health consequences such as the progressive development of stomach ulcers and gastric cancer. European clinical guidelines suggest consulting local H. pylori resistance rates when prescribing treatments, to help ensure the best treatment option is provided. This not only helps to achieve effective eradication therapy but also helps to prevent further antibiotic resistance.

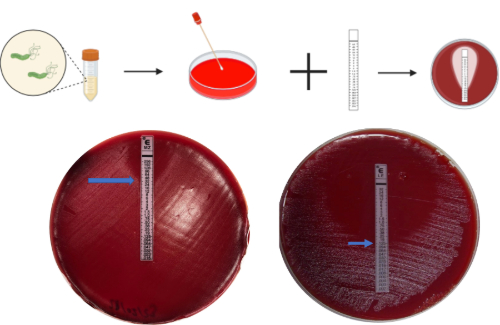

However, little data was available in the UK to help inform clinicians, thus our investigation began to fill this gap. In Nottingham, between 2001 and 2018, 162 patients who were experiencing chronic upset stomachs underwent a gastrointestinal endoscopy and the collection of gastric biopsies for clinical investigation of their symptoms. With their consent we collected extra biopsies for the purpose of culturing H. pylori and testing the resistance of those strains to the most commonly used antibiotics (metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline and levofloxacin). Jo was involved in this process from the start, being present in the hospital endoscopy suite to aid the safe collection of these biopsies. Through careful culturing she managed to isolate H. pylori, which is a tricky task due to it growing much more slowly than other bacteria present on the biopsy tissue. Over the course of several years, a COVID-19 lockdown, and the pouring of many blood agar plates (over 4000 of them!), we managed to work our way through the entire Nottingham Strain Collection. We gathered data on 241 H. pylori isolates using commercial E-test strips, which are impregnated with a range of antibiotic concentrations as a gradient.

This involved inoculating H. pylori in a saline solution, swabbing it onto Muller-Hinton agar mixed with horse blood, applying an E-test strip and reading the concentration from the zone of inhibition after 5 days of incubation. Whilst E-test strips are the accepted clinical diagnostic test for determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and susceptibility of strains, the downside is that they are incredibly expensive, costing 30 times more! As an additional mission, we also tested an alternative method of antibiotic susceptibility testing: disc diffusion. The aim was to see whether this cheaper method gave consistent results when compared to E-test strips.

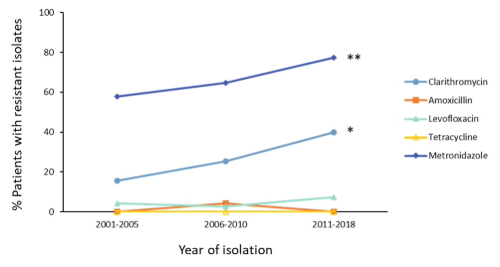

In short, we found that 62% of the isolates we tested were resistant to metronidazole, and 28% were resistant to clarithromycin. The data also revealed that 41% of isolates showed resistance to one of the antibiotics tested, and 27% were resistant to more than one. Only 32% of isolates were sensitive to all of the antibiotics tested. Despite having some ideas of what resistance rates might look like, it still came as quite a surprise when time and time again, the clinical isolates were resistant to metronidazole and clarithromycin. These resistance rates, particularly for metronidazole, were far higher than we had anticipated, and it became clear that the data we were gathering was not only useful but essential.

We also found that throughout the years there was increasing resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole, which recognises the need for the expansion of H. pylori sensitivity testing in the UK. Additionally, out of the four antibiotics that were compared, three of them were found to have identical susceptibility results when comparing E-test strip and disc diffusion methods, with only metronidazole having discrepant results between the two. As such, for clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and levofloxacin, disc diffusion may be a much cheaper alternative for susceptibility testing. For further details on our findings, please read our paper.

This paper helps to bridge a gap in our knowledge of H. pylori in the UK, since very little antibiotic susceptibility testing is carried out. Our work on Helicobacter pylori doesn’t stop there though and we look forward to sharing more in the future about our research and ongoing work, including further analysis into the mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance. Currently, we are performing genome sequencing analysis of resistant isolates and comparing their genomes to those that show antimicrobial susceptibility. Our hypothesis is that higher concentrations (MICs) would be needed to treat strains with more amino acid substitutions at the active site regions. The aim is to get a clearer understanding of the genetic mechanisms behind antimicrobial resistance, and to see how it could inform treatment options in the future. Members of our group are also looking at the immunological response to H. pylori infection and its role in stomach ulcers and gastric cancer, so that we can understand more about why an unlucky 10-15% of people develop these conditions.

Thumbnail: Microscope image of H. pylori