Antibiotics: weapons or signals?

Posted on October 13, 2015 by Anand Jagatia

Bacteria and fungi have naturally been producing antibiotics for millions of years. Over the last century, we have been able to harness the power of these compounds for our own uses to treat infections. But what are antibiotics actually used for, by the microbes that create them?

Classically, the thinking has been for the same reasons that we use them: to kill other bacteria and to defend themselves from attack. But increasingly, scientists have begun to wonder whether this is the full picture. For one thing, natural antibiotic concentrations in soil seem to be too low to actually kill other bacteria. In fact, bacteria can respond to low (or sub-inhibitory) levels of antibiotics in a wide range of other ways, from quorum sensing to gene expression.

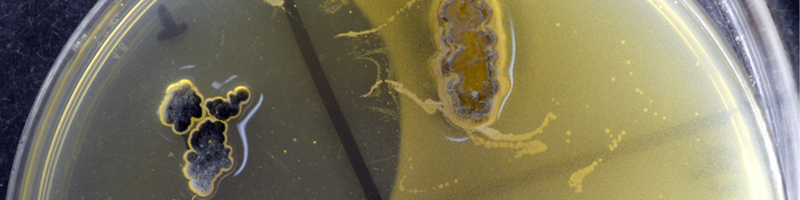

This has led to the idea that antibiotics may function as signals between cells, allowing them to cooperate and communicate with each other. But some recent research from Leiden University claims to show that although antibiotic production may be social, it’s far from cooperative. Bacteria, they say, use antibiotics as weapons.

Streptomyces bacteria produce many of our current antibiotics. The team took 13 strains of Streptomyces from a soil sample and tested the capacity of each strain to inhibit every other strain. They then added a social component: for every pair of bacteria, the team tested whether the presence of a third strain affected the original interaction. This third strain could either:

- elicit inhibition where there was none before

- suppress inhibition where there was some before

- have no effect on the interaction

The group found that in the three-way interactions, bacteria became more aggressive, both offensively and defensively.

“Adding these competitor strains had a huge impact on what cells were able to do – in both directions,” explains Daniel Rozen, corresponding author on the paper. “Often we found that bacteria could inhibit the growth of strains they couldn’t before, but also suppress antibiotic production in other strains.”

The authors argue that this kind of behaviour is distinctly competitive, and not cooperative, which supports the “antibiotics as weapons” theory.

The social interactions between soil bacteria likely have a big impact on the antibiotics they produce. But in general, it’s difficult to study bacteria in the lab without breaking up these complex networks of induction and suppression. Intuitively, it makes sense that bacteria would produce more antibiotics in the presence of other strains, especially when resources are limited, because they are energetically costly to produce.

“We were surprised by how widespread these responses were, even in our small sample,” says Daniel. “It looks like we’ve been missing a major part of what happens between bacterial competitors.”

The team are now hoping to identify the mechanisms that allow these bacteria to switch on the killing of other strains. If they are successful, this research could provide new way for unlocking novel antibiotics that we don’t know about, because they are only produced in the presence of other ecologically relevant strains.

“Some of the added strains were very good at inducing antibiotic production in lots of other species,” Daniel says. “If we can find a generalised inducer, that could be really valuable for drawing out new antibiotics from bacterial collections we already have.”

Abrudan MI, Smakman F, Grimbergen AJ, Westhoff S, Miller EL, van Wezel GP, & Rozen DE (2015). Socially mediated induction and suppression of antibiosis during bacterial coexistence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112 (35), 11054-9 PMID: 26216986

Image: El Bingle on Flickr under CC BY-NC 2.0