Caesarean section infants’ gut microbiome differences are driven by delivery mode, not by antibiotic exposure.

Posted on August 2, 2024 by Sophie Leech

Sophie Leech takes us behind the scenes of their latest publication 'Delivery mode is a larger determinant of infant gut microbiome composition at 6 weeks than exposure to peripartum antibiotics' published in Microbial Genomics.

Hi! My name is Sophie Leech. I’m a PhD candidate in Marloes Nitert Dekker’s lab group at the School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. This research was conducted with samples collected in the Queensland Family Cohort pilot, an ongoing birth cohort based at the Mater Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia, led by Professor Vicki Clifton.

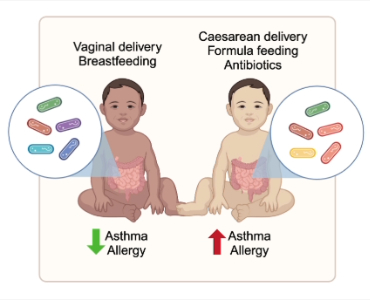

The healthy development of the infant gut microbiome is thought to be important for healthy infant development. There is evidence that suggests the infant gut microbiome has changed alongside industrialisation, with increasing antibiotic use, decreased breastfeeding and increased rates of Caesarean sections thought to disrupt early infant gut colonisation and development. It is hypothesised that this change may drive the increases in immune associated disorders seen in industrialised countries like asthma and allergy. Therefore, it is vital that we understand what factors are important for healthy infant gut development and the ways in which they alter the composition of the infant microbiome.

Delivery mode may be one of the most frequently reported and strongest influencers on the early infant gut. During a vaginal delivery, it is thought that the infant is exposed to maternal gut microorganisms as the infant exits the birth canal, which provides access to the vital early colonisers for normal gut microbiome development. However, Caesarean section infants do not pass through the birth canal, missing out on this early exposure. This is supported by consistent reports of absent or low levels of key taxa such as Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium in the guts of Caesarean section infants, despite their presence in the maternal gut.

With this interest in the early infant gut colonisation, during my undergraduate honour’s year, I, together with my supervisors Marloes Dekker Nitert, Danielle Borg, Kym Rae and Vicki Clifton, conducted a study examining the effect of delivery mode and breastfeeding on the infant gut microbiome. In this study we also examined the maternal and breastmilk microbiomes as potential sources of the infant gut microbiome using shotgun metagenomic sequencing. In this small study, while we saw a strong effect of delivery mode, two of our vaginally delivered infants had mothers who were administered antibiotics during or in the weeks following birth, and these infants clustered closely with the Caesarean delivered infants.

This raised the question of whether routine antibiotic use during Caesarean delivery may be driving the differences that we were seeing. Turning to the literature we saw that most studies did not account for the potentially confounding effect of routine antibiotic use on the reported effects of Caesarean delivery, and most were limited to less informative 16s rRNA sequencing. Therefore, when I returned to Marloes Nitert Dekker’s lab for my PhD, we decided to expand this initial study to include vaginally delivered infants whose mothers were similarly administered antibiotics during labour and delivery.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, this expanded study demonstrated that delivery mode itself was a greater driver of differences in the infant gut microbiome, while antibiotic exposure during delivery had only minor effects (a good reminder about not drawing conclusions based on two people). While this research should be repeated in a larger study, this result is good news in some ways, as mothers have superior outcomes with pre-incision antibiotics compared to after cord clamping. However, this means development of alternate methods for restoring Caesarean section infant gut microbiomes following Caesarean section is necessary.

Some work has previously been conducted trying to correct the gut microbiome of Caesarean section infants, though no method has yet made its way into clinical practice. Some studies have demonstrated some success with vaginal swabs, though this doesn’t appear to fully restore the microbiome to that of a vaginally delivered infant. One study has demonstrated that maternal faecal matter exposure may restore the Caesarean infant gut to more like that of a vaginally delivered infant, though the risk of transferring harmful bacteria is a concern. Carefully selected biologically-based probiotics could also be a solution.

While rates of Caesarean section could be safely reduced in some areas, in many cases a Caesarean section is a necessary life-saving procedure. Therefore, future research into restoring gut microbiome health of Caesarean section infants is needed.