Flagella, more than meets the eye…

Posted on September 3, 2013 by Benjamin Thompson

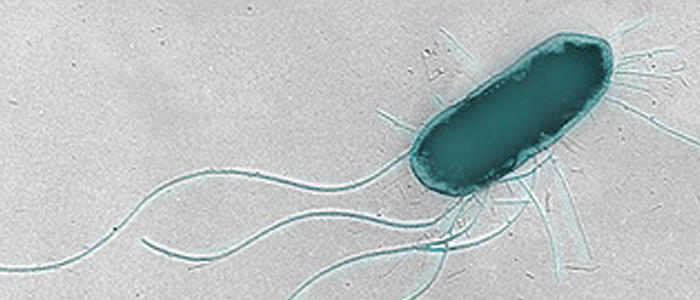

Yesterday at the SGM Autumn conference, we learnt a lot about bacterial flagella, which appear to be more than just propellers for swimming bacteria. Eliza Wolfson tells us about her research in E. coli and what it’s taught us.

Enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) can be a very nasty bug. Strains of this bacterium are a cause of foodborne disease and kidney failure; E. coli O157:H7 is perhaps the most infamous strain and is often transmitted via improperly cooked, contaminated meat products.

Cattle are the main reservoir for EHEC, with the bacteria living in a remarkably specific part of the cow: the last 5 cm of its GI tract. This makes it a good place for the bacteria to escape – as the old joke goes, ‘What do you get if you sit under a cow? A pat potentially lethal strain of E. coli on the head…’

Controlling the EHEC in the cattle reservoir seems like a good bet if we want to prevent the disease in humans. Interested in how these bacteria colonise the cow GI tract, researchers looked at EHEC flagella, to see if they were involved.

A common assumption is that flagella are mainly used by bacteria for locomotion, spinning like a ship’s propeller to move them around their environment. It turns out they also do a whole lot more. Working on the idea that the flagella were helping EHEC stick to cows’ intestinal walls, Eliza Wolfson, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, began searching for proteins that the flagella were binding to.

Few interactions were found between purified flagella and proteins normally present on the surface of cow intestinal cells. Instead, Eliza saw an interaction between flagella and cofilin, a cytoskeleton-associated protein found within the intestinal cells. Closer investigation revealed that EHEC flagella were penetrating into the host cells, while the body of the bacteria remained stuck to the outside. And it wasn’t just EHEC doing this – Salmonella Typhimurium, another intestinal pathogen, does something similar with its flagella, which interact with a different cytoskeletal protein, actin.

The reasons that these species do this are still unclear. There are two hypotheses: the first is that by interacting with the host cell’s internal scaffolding, the pathogenic bacteria can anchor themselves securely within the GI tract. The second is that the bacteria are ‘hiding’ from the host’s immune system, as Flagellin – the protein that makes up much of flagella filaments – is recognised by the immune system.

This observational study is only the beginning of this work. As Eliza explains, “We’re just putting the pieces together. We have seen flagella from gut pathogens going inside host cells and this type of interaction may be more widespread. This work opens up new ideas for how flagella are involved in pathogenesis; they aren’t just for motility.”