Friends with benefits, or exploitation?

Posted on February 11, 2016 by Anand Jagatia

Endosymbioses – where one species lives inside another – are found throughout microbiology. For example, Zooxanthellae are protozoa that live inside corals, the marine invertebrates that build coral reefs. And some plant roots contain nodules of Rhizobium bacteria that provide them with forms of nitrogen essential for growth.

Traditionally, scientists have thought that these relationships evolved because both the host and the symbiont bring something to the party, with both benefitting equally from the interaction. But the puzzling thing about such mutually beneficial arrangements is how they remain stable over time. The evolutionary temptation to “cheat” – i.e. for one party to find a way to take a little more and give a little less – would be huge.

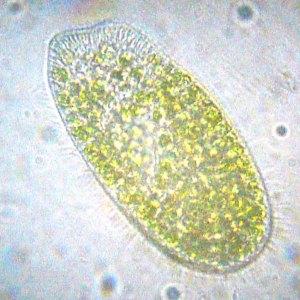

One potential explanation is that endosymbioses aren’t actually based on mutual benefit at all – instead, they’re based on one species exploiting the other. Testing this idea experimentally has been difficult, but recent research has been able to do just that in a symbiosis between the protozoan Paramecium and the algae Chlorella. The verdict? Exploitation.

In this particular relationship, the alga is the symbiont and lives inside the Paramecium, which is the host. The alga can perform photosynthesis, so provides the host with sugars that it makes using light. In turn, the alga receives nitrogen compounds from the Paramecium that it needs for growth. So far, it seems like a pretty cosy arrangement. But when you compare how the two species fare on their own, it’s clear that the Paramecium is getting the better deal.

As an analogy – imagine a symbiont inside a host as an employee working for a company. In a mutualistic relationship, the employee gets a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work. In an exploitation, the employee gets an unfair wage, being paid less for the same amount of work.

The Paramecium–Chlorella system is more like the latter. “We reduced the interaction down to its bare bones,” says Dr Chris Lowe, one of the authors of the Current Biology paper. “We pulled them apart and measured the growth of each species separately versus together. We found that the symbiont could always do slightly better without the host.”

The researchers measured growth in the two species at different light levels. At low light, or in the dark, harbouring symbionts is actually worse for the host than being alone, because the symbionts perform little or no photosynthesis but still require feeding with nitrates. It’s like a business having to pay workers that aren’t doing any actual work. But as light increases, the benefits to the host also increase because the symbionts produce more sugar.

In contrast, the team found that at all light levels, the symbionts showed higher growth alone than they did inside the host, which indicates they were being exploited. In line with this theory, the authors also showed that the host had a set of control mechanisms to maximise its gains from the symbiont. At high light levels, when the algae perform lots of photosynthesis, the host gets more ‘bang for its buck’ per symbiont. When your workers are more efficient, you don’t need as many, and so the Paramecium gets rid of the algae it doesn’t need.

In addition, when light levels drop below a critical level where the host no longer benefits, the symbiosis itself began to break down. “At low light levels, we started to observe populations of free-living algae,” explains Chris. “There is a hint that the algae might be able to escape when the host stops benefitting from the interaction. But at higher light levels, the host regulates its symbionts much more tightly.”

Although the authors were able to demonstrate an exploitation in the lab, in the real world the algae may be receiving other benefits from its host, such as protection from predation. To test this, Chris and his colleagues are hoping to introduce predators into the interaction to measure the costs and benefits of symbiosis to each species.

“There is a lot of theory about whether endosymbiosis should be mutualistic or exploitative, but very little experimental evidence,” says Chris. “Our experiment shows that fundamentally, what we’ve always thought of as a mutualism is almost certainly an exploitation.”

Lowe, C., Minter, E., Cameron, D., & Brockhurst, M. (2016). Shining a Light on Exploitative Host Control in a Photosynthetic Endosymbiosis Current Biology, 26 (2), 207-211 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.05