Has TB had its time?

Posted on September 26, 2018 by Laura Cox

In 19th century Europe, the Industrial Revolution brought on a new age of technological advancement. Cities saw an explosion in population growth. But with this came something more sinister - a mysterious disease which killed as many as one in four people. Factories opened and jobs in towns and cities grew in abundance. Urban populations boomed whilst living conditions deteriorated. There was little-to-no sanitation, and more and more people crammed into smaller living spaces; a perfect breeding ground for disease.

Those infected would become thin and pale, suffer from fevers and night sweats and eventually cough up blood. Named after the weight loss it caused, ‘consumption’ spread throughout cities.

In fact, so many people were dying from consumption it became fashionable. The disease was most common in poorer members of society, including poets and artists, and was seen as a ‘romantic disease’. The pale, waiflike appearance of those in the later stages of the disease was seen as desirable, and women would apply pale makeup to mimic those who were sick.

This was not a new disease, however. It has gone by many names: ‘phthisis’ in ancient Greece, ‘tabes’ in ancient Rome and ‘the white plague’ in the 1700s. Evidence of the infection has been found in human remains dating back as far as 9000 years.

Despite its fashionable status, research into preventing consumption progressed throughout the 1800s. In 1865, a French military surgeon called Jean Antoine Villemin proved that the disease was infectious. Yet still scientists could not figure out the cause.

Professor Robert

Koch

Seventeen years later, in 1882, Robert Koch proposed Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the cause of consumption at the Physiological Society of Berlin. He gave his lecture Über Tuberculose on March 24, now known as World TB Day.

Finally, the cause of the disease was known, and the race began to find a cure.

In 1906, a vaccine was developed using a type of tuberculosis that commonly affects cattle. The BCG vaccine proved a great success, and as cases fell, it was believed the disease could be completely eradicated.

However, these hopes were dashed in the 1980's, when multi-drug resistant strains of TB emerged alongside a new disease - HIV. Deaths from TB were on the rise, and the World Health Organisation declared a global health emergency in 1993.

Today, approximately 10 million people are infected with tuberculosis worldwide. And in 2017 - 135 years after its discovery - M. tuberculosis was one of the top ten causes of death and killed 1.6 million people.

What exactly is tuberculosis?

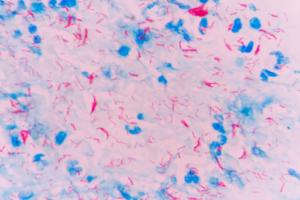

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a slow-growing, rod-shaped bacterium. It is spread from infected people in small water droplets, usually by coughing and sneezing.

The bacteria enter the lungs and causes lesions and cavities within the lung tissue. However, it can can also affect the bones, nervous system and glands.

Tuberculosis infection can usually be cleared by the immune system or 'walled off' in granulomas. This prevents the infection from spreading and causing disease and is called latent infection. It is predicted that as many as 1.85 billion people are infected with tuberculosis and do not know about it.

Of these latently infected people, it is estimated that 5 - 15% will develop active tuberculosis. The risk is higher for people with weakened immune systems, such as HIV patients, people who are malnourished or diabetics.

If someone develops active tuberculosis, the symptoms may start slowly, preventing many people from seeking treatment quickly. This gives the disease time to develop further and get worse. Without proper treatment, nearly 45% of people with active tuberculosis die.

How is tuberculosis treated?

Tuberculosis infection can be treated and cured by antibiotics. In patients with active tuberculosis, they usually are prescribed a course of four antibiotics for six months.

Some strains of the bacteria have evolved to be resistant to certain antibiotics, and the increase of multiple drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is a growing concern.

Why is it so difficult to study?

Mycobacteria have a thick cell wall and cannot be visualised using Gram-staining. Koch discovered M. tuberculosis by developing a new staining technique to make the bacteria visible.

The slow growth rate of M. tuberculosis means that even in optimal conditions the bacterium splits only once every 24 hours. Because of this, when researching M. tuberculosis in the lab, it can take over three weeks to get visible colonies.

Today, in New York, The United Nations Assembly is holding a high-level meeting with the theme 'United to end tuberculosis: an urgent global response to a global epidemic'.

This is the first ever high-level meeting on tuberculosis, and is hoped to accelerate efforts in ending tuberculosis, saving millions of lives worldwide.