How studying a unique cluster of non- toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae led to a change in public health guidance

Posted on August 8, 2023 by Dr Norman Fry

Dr Norman Fry takes us behind the scenes of their latest publication, 'Household transmission of non-toxigenic diphtheria toxin gene-bearing Corynebacterium diphtheriae following a cluster of cutaneous cases in a specialist outpatient setting' published in Journal of Medical Microbiology.

Hello, I’m Norman Fry, a Clinical Scientist in the Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division, at the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), London.

As part of our surveillance role at UKHSA, we monitor a number of infectious diseases, including diphtheria. Part of this work involves performing specialist tests in our laboratory to confirm the identity of submitted isolates and characterise them, which helps in case management and control.

Diphtheria is a serious, potentially fatal bacterial infection in humans caused by toxigenic strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae or Corynebacterium ulcerans. Cases due to toxigenic C. diphtheriae are usually associated with travel to a country where diphtheria regularly occurs (endemic). Whereas cases caused by toxigenic C. ulcerans are associated with close contact with animals (particularly cats and dogs) and this type of infection is known as zoonotic. Although diphtheria is relatively rare in the UK (typically less than 10 cases per year), in the last few years there has been an increase in cases due to both species. The rise in cases of C. ulcerans is likely due to increasing contact with pet ownership and exposure /contact, whilst the increase in C. diphtheriae cases seen in 2022 was associated with cases in asylum seekers.

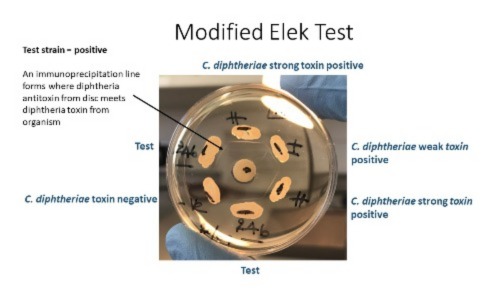

To test for toxigenicity, strains are sent to our laboratory (the national reference laboratory for diphtheria) and we perform PCR to determine if the toxin gene is present (which only takes a few hours) and then confirm if the toxin is expressed using an immunoprecipitation test called the Elek test (after Stephen Elek) which can take 24-48 hours. Toxigenic strains are PCR toxin gene positive and Elek positive (Figure).

Our most recent paper is about an interesting group of strains know as non-toxigenic toxin-gene bearing (NTTB) C. diphtheriae. These organisms can carry part or all of the diphtheria toxin gene but cannot express the diphtheria toxin. This is usually due to variation in DNA bases within the toxin gene operon. Using the two tests above these NTTB strains are PCR toxin gene positive: but Elek negative. Because these strains have a theoretical risk of becoming toxigenic, they present a difficult challenge in terms of their public health management.

Our paper describes a cluster of NTTB cases detected in patients attending a skin clinic in a London hospital, with a further two cases detected in close household contacts of one of the patients.

We initially investigated this cluster as part of our usual outbreak response whenever we identify a PCR toxin gene positive strain. After the initial incident was closed the subsequent transmission from one of the original cases to two close contacts, after 18 months and 42 months respectively, presented a unique opportunity to see whether any changes in the genomic DNA had occurred.

The nature of this incident meant it required expertise from a range of different public health professionals. This was one of the most exciting aspects of this work, with the coming together of healthcare professionals in so many different areas and specialities: clinicians, nurses, health protection, epidemiologists, microbiologists and bioinformaticians. This is a great example of collaborative work in public health.

As we found no evidence of any change in the toxin gene or reversion, we argue that this possibility of NTTB strains becoming toxigenic is unlikely. We used this study to update and improve the guidance for dealing with such strains and incidents in the future.

The Modified Elek test.

Although PCR has greatly improved the ability to rapidly detect the diphtheria toxin gene (tox). The modified Elek test remains the gold standard to confirm expression of diphtheria toxin (DT).

A filter disc pre-soaked with diphtheria antitoxin is placed in the centre of the plate. Positive (diphtheria toxin expressing) and negative (diphtheria toxin non-expressing) control strains are streaked equidistant from this disc along with the test strains. After 24 to 48 hours incubation a line of precipitation forms if the toxin is expressed (where the toxin and anti-toxin meet).

Toxigenic strains are PCR tox positive and Elek positive; non-toxigenic strains are all Elek negative but can be either (i) PCR tox negative and Elek negative or (ii) PCR tox positive and Elek negative. Strains which are PCR tox positive and Elek negative are known as non-toxigenic toxin gene-bearing (NTTB).

We must continue to be vigilant in monitoring and preventing infectious diseases including diphtheria. Keeping up to date with routine vaccination against the vaccine-preventable diseases is the best defence. Good awareness in hospital laboratories and surveillance, rapid identification, treatment, and management are all essential parts of this process.

The application of whole genome sequencing to analyse the genomes of both non-toxigenic and toxigenic C. diphtheriae is giving us much better insights into the spread of this organism.

In conclusion, we think the future is exciting and we are involved with a large collaboration with colleagues in many countries to analyse the toxigenic C. diphtheriae strains from asylum seekers in Europe.