Life at the Extremes

Posted on September 18, 2018 by Dr Naji Bassil

Microbes can colonise and transform environments that are considered harsh for humans. This was demonstrated by a team from the University of Manchester’s geomicrobiology group at Bluedot festival in their stall ‘Life at the Extremes’. This music festival, held at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, celebrates science, art and culture. This year, Bluedot was held between 19 and 22 July.

Visitors to the ‘Life at the Extremes’ stall were amazed by the range of environments where microbes have been found, and the diversity of microorganisms in many environments that are considered hostile for life on Earth. For example, Thermus aquaticus was isolated from the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park, where the temperature ranges between 50 and 80oC, while Bacillus arseniciselenatis was isolated from Mono Lake in California that shows high pH, salinity and high concentrations of arsenic.

The stall had a variety of activities to appeal to a range of visitors

Young visitors of the ‘Life at the Extremes’ stall imagined and built their own biosphere, with coloured sand layers representing different environments of the biosphere, for example ocean floor/sediment, deep-sea hypersaline brine lakes, black smokers, and surface water. They then learned which extremophilic (extreme-loving) microbes are best suited to live in each environment.

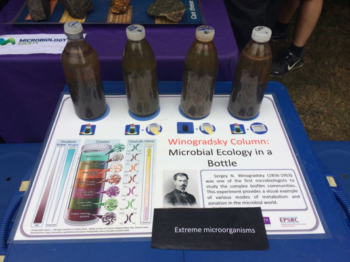

They also observed how microbial communities transform their immediate environment and form separate layers in Winogradsky columns, depending on the electron donors and acceptors that each community utilises. In this particular example, the young scientists observed that as the oxygen concentration decreased (towards the bottom), different sulphate-reducing microbial communities grew when cellulose and sulphate were added to sediments and water in sealed plastic bottles. The different communities even changed the colour of the sediment depending on the pigments they produce.

Then, the young geologists investigated different rock formations and attempted to answer the question ‘Which rocks and minerals can support/are required for life?’

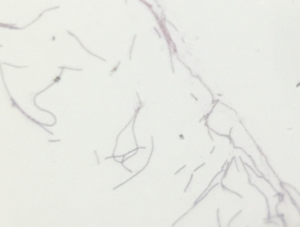

When asked ‘How do you know if something is alive?’, the young microbiologists were able to observe cyanobacteria growing in cultures and under a foldscope (a paper microscope that provides 140x magnification) and a light microscope.

- ...And Pseudanabaena catenata under the

light microscope at 400x resolution

- They observed Gram stained Anabaena sp.

under the foldscope at 140x resolution...

They were also able to see how Geobacter sulfurreducens can reduce ferrihydrite to biomagnetite, which is attracted to a magnet through magnetism rather than magic!

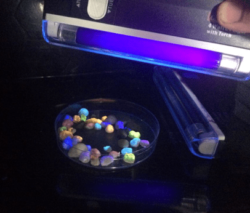

The young microbiologists then isolated unknown bacteria (white stones) and identified the different species (different fluorescent colours) using our very own black box UV DNA sequencer.

They also identified microbial processes that can be utilised to convert human ‘waste’ into new resources, thereby reducing pollution of the environment.

The young computational biologists modelled bacterial colonisation under different conditions, and concluded that although bacteria are found in various extreme environments, each bacterium has evolved machinery to live in a specific environment.

The young scientists assembled a jigsaw puzzle of the different components of a hypothetical super bacterium, and identified the machinery that helps it tolerate different extreme conditions.

In the end, everyone took a ‘Cellfie’ with the microbes.

Overall, the range of activities presented at our ‘Life at the Extremes’ event increased people’s interest in environmental microbiology, giving a new dimension to the topic away from the focus on microbiology and human health, especially the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ bacteria categorisation. It showed the amazing diversity of microorganisms on Earth, highlighting the mechanisms they utilise to survive in extreme environments.

Funding from the Microbiology Society was integral in delivering this activity. The material used to build most activities, in addition to travel expenses for members of the team were supported from the Microbiology Society Education and Outreach grant. The grant application process was straightforward, and we got the acceptance email within two weeks of applying, which gave us ample time to prepare the material for the festival. The Education and Outreach grant and other funding schemes from the Microbiology Society help microbiologists engage with the public, start new collaborations, attend and present at conferences, etc. These are vital for early career microbiologists like us to progress our careers.

We thank the Bluedot festival organisers and the Microbiology Society for giving us the opportunity and helping us deliver a successful event.