Living light at the National Eisteddfod of Wales

Posted on September 3, 2018 by Dr Catrin Williams

I am a multidisciplinary researcher, currently based at the School of Engineering at Cardiff University. My research transgresses a number of disciplines, including microbiology (my first love!), human cell physiology and microwave engineering. My work explores the use of bioluminescence as a non-invasive, label-free reporter to understand interactions between microwave fields and biological systems.

For my latest outreach project, I decided to dip into a new area, namely the arts. Inspired by the work of Dr Siouxsie Willes and Hunter Cole, and in line with the celebrations of The Year of the Sea in Wales, I teamed up with Lisa Porch, a textile artist based at Hereford College of Arts, to produce a living art display using the bioluminescent marine bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri. This display was exhibited at the National Eisteddfod of Wales from 5-10th August, 2018.

Living light at the National Eisteddfod of Wales

The National Eisteddfod is an annual festival which celebrates language and culture in Wales. Its modern roots were established in 1861, but its history can be traced back as far as 1176. Every year it attracts 150,000 attendees and 6,000 competitors in all aspects of the arts.

Science and technology have played an important part in the festival for over 40 years, and today the Science Pavilion is one of the most popular locations on the ‘Maes’ (site). The aim of the Pavilion is to showcase science in Wales to people of all ages, and to inspire children and young people to study the STEM subjects through the medium of welsh.

I saw this as a prime opportunity to engage a broad audience in bioluminescence. Specifically, what is bioluminescence? How is bioluminescence used in nature? How do we as scientists use bioluminescence in our research? I recently elaborated on this in my Conversation article “What is bioluminescence and how is it used by humans and in nature?”

Although bioluminescence is dubbed as possibly the most common form of communication in nature due to the numbers and diversity of animals in the deep sea that are estimated to use this tool; to witness this phenomenon is a rare privilege. Therefore, to achieve a lasting impression on our visitors, I decided to bring bioluminescence to the masses by constructing and exhibiting a glowing and living art display at the Eisteddfod. The final exhibit, “Golau Byw” (Living Light), consisted of 100 regular sized circular Petri dishes containing Photobacterium agar. A letter was painted onto each of these which spelled-out the first verse of a famous welsh folk song “Ar lan y môr” (Beside the Sea).

The “Living Light” bioluminescent art display captured via time-lapse photography over a 72 hour period using a Go-Pro camera.

Getting to this stage took a careful planning and a lot of trial and error. I had previously exhibited at the 2016 Eisteddfod in Anglesey with only a few plates of bacteria - which didn’t survive the journey! So setting up 100 plates as an artistic display was a little daunting to say the least.

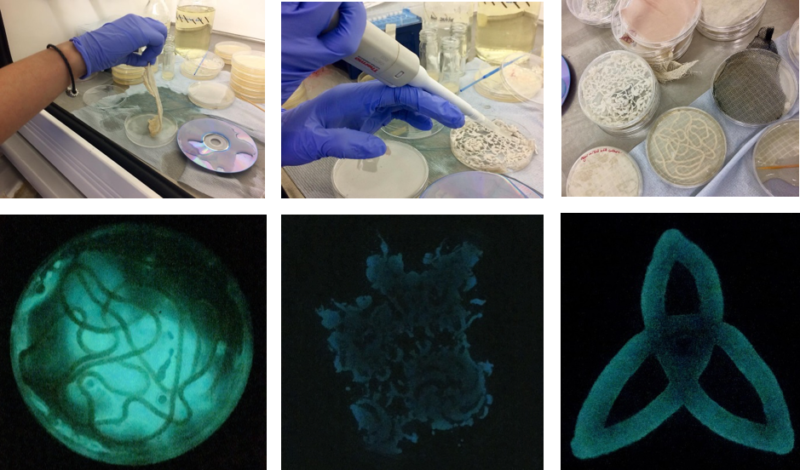

Lisa and I began by experimenting with incorporating different textiles and other materials into agar, printing the bacteria onto the agar surface using lace, and coating different objects (like leaves and pictures) with a thin film of agar and painting the bacteria on top. We managed to get some very effective results with some of the materials, but others didn’t work at all! In the end we decided that letters were the most effective of these, being the easiest to set-up and reproduce, and giving the option of incorporating welsh culture, through our choice of verse.

- Top: Experimenting with different textiles in preparation for the bioluminescent art display.

Bottom: Some examples of the results achieved after overnight incubation of Aliivibrio fischeri with different textiles, including string, lace and a Celtic knot painted on an agar plate.

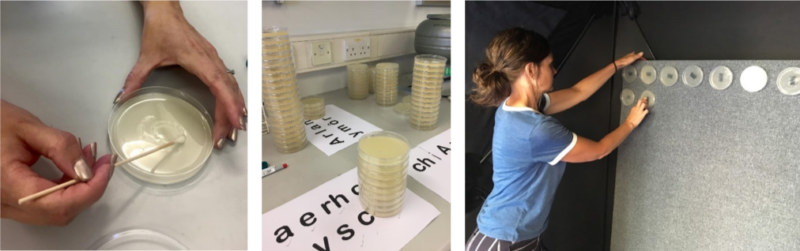

From a practical perspective, the bacteria were easy to prepare, handle and maintain. Five millilitres of artificial seawater buffer was poured on top of an agar plate containing established colonies of A. fischeri, which was then grown for 24 hours at 25°C. This dense culture was then transferred to a test tube and used as the paint for the display. Swabs were used as the paint brushes, their rounded ends working particularly well to trace the letters onto the agar surface. The high salt content of the media meant that any contaminants were kept at bay (at least in the short-term), meaning that it was not necessary to work under completely sterile conditions. After drying, the plates were attached to a 1.2 x 1.2 m poster board and left to grow overnight in preparation for the live display.

- Preparation for the “Living Light” bioluminescent art exhibition. Letters were drawn onto agar plates using a suspension of Aliivibrio fischeri. The plates were then left to dry and stacked in order. Dried plates were transported to the festival site where they were attached to a poster board within a blackout tent for display throughout the week.

To my amazement, and despite the warm temperatures recorded in the Science Pavilion (up to 30°C on some occasions!), the bacteria kept glowing for the entire week. The shape of the letters facilitated the extended growth, as the bacteria migrated outwards towards the sides of the agar in search of more nutrients. The display itself really sparked an interest in visitors throughout the week. Entering the blackout tent to view the display provided an intimate and immersive experience, with reactions ranging from “oooohs” and “ahhhhs” as the glow appeared before their eyes, to excitement, especially from young children, at being able to interpret the letters and even sing the entire verse!

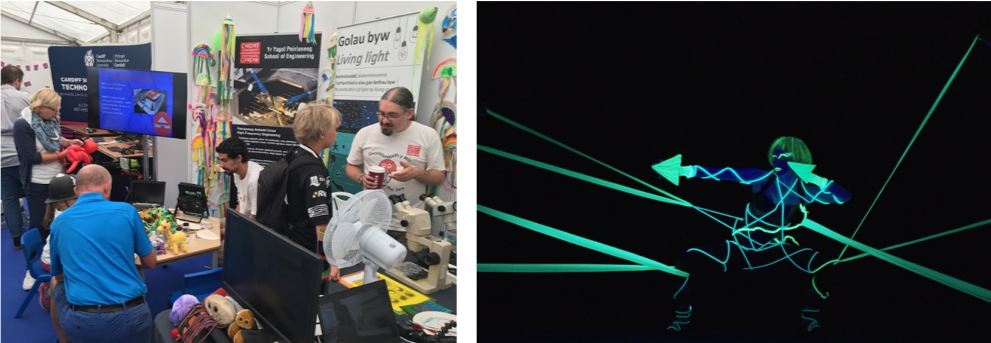

The display also linked nicely to other activities we had planned. Children visiting the display had the opportunity to make their own glow-in-the-dark paintings and fluorescent jellyfish (800 of which were made over the course of the week).

Visitors also had the opportunity to view glowing juvenile zebrafish containing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the microscope (courtesy of Dr Emyr Lloyd-Evans’ Research Group). Children also enjoyed taking away a free glow stick to remind them of their experience. Additionally, bioluminescence was the theme of the evening entertainment, which ran throughout the festival, in “Carnifal y môr” (Carnival of the Sea). This consisted of a procession of glowing sea creatures followed by a display of moving images projected on a water screen. This was conceptualised by artist Megan Broadmeadow with music provided by signer composer Gruff Rhys, in collaboration with Butetown Carnival.

- Left: Cardiff University researchers busy making fluorescent jellyfish and discussing bioluminescence on the “Living Light” exhbition at the National Eisteddfod.

- Right: A performer at the Carnival of the Sea at the National Eisteddfod

The bad

On the second morning of the festival (after a sleepless night worrying if the bacteria would still be glowing the next day!), I returned to find all the Petri dishes piled in a heap on the floor. The hot and humid conditions within the tent meant that the plates had dropped off the poster board overnight. Despite their eventful night, the bacteria were still glowing, so we quickly placed the plates back on the poster board and wrapped the entire display with cling-film. This approach worked well and lasted throughout the week without a repeat performance! It also provided an additional barrier between the bacteria and the curious hands of some of the visitors!

The ugly

Perhaps unsurprisingly, towards the end of the week I began to notice the appearance of fungal growth on the plates, which looked a little unsightly in day light. However, the bacteria continued to glow regardless of their companions! At the end of the festival, the plates were promptly removed from the site and transported back to the University for disposal.

What next?

Serendipitously, the warm weather experienced across the UK from June-August, brought with it increased sightings of marine bioluminescence, especially around Wales. This has prompted crowds in their hundreds to venture to the coast in the middle of the night in search of this phenomenon, likely caused by blooms of the dinoflagellate Noctiluca. An accompanying Facebook group (“Bioluminescent Plankton Watch – Wales”) has been set-up and now contains over 5,500 members. The group is a valuable resource of information and I am currently working with the group’s admin to develop a citizen science project to map the occurrence and frequency of these sightings across Wales in order to develop a better understanding of the conditions which lead to these bioluminescent blooms, such as temperature and level of pollution. In addition, as a legacy to this project, I teamed up with TV Editor, Iwan Evans (also my husband!), to produce a short bilingual film on bioluminescence which was shown throughout the week at the Eisteddfod and now hosted on YouTube. This will be edited for future outreach events as well as being a useful online resource.

Bioluminescence captured at Three Cliffs Bay on the Gower Peninsula.

As a fluent welsh language speaker, and in order to hit the Welsh Government’s objective of reaching 1 million welsh language speakers by 2050, I am passionate about communicating through the medium of welsh at any given opportunity. This year’s Eisteddfod, held at Cardiff Bay, has been the most inclusive yet, being described as “a festival for everyone… whatever their background”, with free entry to all. This has brought with it a prime opportunity to engage with a broad audience on a microbiological topic as well as increase awareness and use of the welsh language in an interactive and inclusive setting.

Acknowledgements

My research at Cardiff University is sponsored by a Sêr Cymru II Fellowship from the European Regional Development Fund, via the Welsh Government.

Support for this project came from an Outreach Grant provided by the Microbiology Society. I have been a member of the society since 2010 and have received a number of great benefits, including a Microbiology Society Conference Grant and Scientific Meeting Travel Grant, which have enabled me to attend the annual conference, as well as present at an international conference as a PhD student. The Society therefore continues to play an important part in my development as an early career researcher, providing unique opportunities to expand my research horizons.

Last but not least, the success of the ‘Living Light’ exhibit would not have been possible without the invaluable help of an army of volunteers in the lead-up and during the festival itself. A big ‘THANK YOU’ to everyone involved!