From Lab Bench to Bar Stool: Storytelling Strategies for Public Science Talks

Posted on June 18, 2025 by Dr Michael Shaw, University of Lincoln

Sharing our research with the public is one of the most rewarding—and challenging—parts of being a scientist. Whether at a conference, in a classroom, or over a pint at a pub, we have a responsibility to make science accessible, engaging, and meaningful. Public engagement with science and outreach events are special because here we have members of the public who have chosen to spend their valuable time engaging with science, and as educators and scientists, there is a responsibility on us to share our knowledge and help to enhance public understanding of science.

So, I was incredibly happy to be invited to present my research on phage biology at The Pessimist Bar in Lincoln, as part of the Pint of Science event in May 2025. Pint of Science is an annual, global, science festival that brings scientists to local pubs, bars, and cafés to share their research with the public in a relaxed and accessible way.

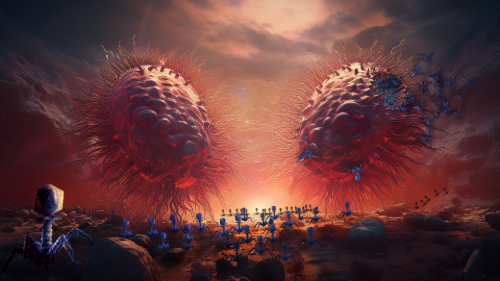

This meant an exciting challenge; as many of us will have faced with public science talks, to write a presentation that didn’t overload members of the public with technical jargon, unnecessary scientific detail, and didn’t alienate my audience by talking over their heads. In an attempt to make complex topics more accessible, I doubled-down on story-telling pedagogy, framing the talk around the idea of phage-bacteria interactions as a war and evolutionary arms race. I used story mechanics and analogies to help set my pitch and complexity in my best attempt to keep the audience engaged.

Overview

The goal: engage a public audience with the fascinating world of phage biology, whilst enjoying a drink or two in a quaint bar on a Tuesday evening.

The challenges:

- Writing something that is engaging: Engaging a diverse audience with varying levels of educational backgrounds means striking the right balance to keep everyone interested.

- Balancing simplification whilst maintaining scientific accuracy: To explain the interactions between phage and bacteria, DNA sequencing, and the genomic characterisation of phage in a way that is understandable but is still an accurate and true representation of the science.

- Pacing and timing: Finally, all this needs to be achieved with a short, snappy timeframe, in this case 20-minutes meaning there are decisions to be made about what to include and what to leave out.

Crafting a Narrative: Engaging Through Story

Throughout the talk I wanted to weave in storytelling, inspired by storytelling pedagogy literature. Storytelling is great for making complex topics easier to understand and more engaging. Storytelling aids in creating meaningful links between theory and practice and can enhance reflective learning (McDrury and Alterio, 2003). The plot device; an epic war between mortal enemies bacteriophage and bacteria. This story approach helped to direct my choices in the selection of analogies and language used throughout the talk; from phages’ ‘subterfuge’ attack, and bacteria’s ‘disguise’ (cell surface modification), and ‘security guards to remove trespassers’ (restriction enzymes).

At around the halfway mark, I made a conscious nod to the fourth wall, acknowledging the limitations of using storytelling to explain scientific details. This allowed me to dive deeper into the concept of adaptation and selection by dissecting the ‘behaviours’ described in the story narrative in relation to the genes responsible. Now, spiralling back to those phage-bacteria interactions (Bruner, 1960), I was able to revisit the same topic with an increased level of detail. The spiral curriculum will be familiar to microbiologists, you’ll recall when we learnt the basics of the central dogma early on in our education before later revisiting this to explore the complexities of transcription and translation.

Simplifying Without Dumbing Down

One of the biggest challenges was figuring out the right level of detail and complexity for the talk. I realised that a specific challenge of the Pint of Science event is that I knew absolutely no details about the audience. A quick hello to a few people in the crowd identified that we had a crowd of biology teachers in the room, someone that works in pharmaceutical clinical trials, someone that worked in sewage treatment, and a range of other backgrounds.

Some choices, I was able to decide relatively easily. For example, when talking about phage construction in relation to the genes and associated proteins, I mentioned the head, tail, and tail fibres but skipped the details about DNA packing. The DNA regulation genes, whilst vital to the phage, didn’t form a critical part of storytelling for a public audience to understand what a phage is.

A tougher decision was whether to cover both lytic and lysogenic phages. The general behaviours of lytic phages fit a simple narrative in the analogy of war, however delving into the intricacies of lysogenic and temperate phages makes the narrative more complex. I initially included a section on lysogenic phages but made the tough decision to cut it during editing. Was this the right choice? The 20-minute limit and the storytelling approach influenced my decision, but on reflection I am constantly wondering whether I have painted an incomplete picture of bacteriophages. In a taught class, I might be able to justify this choice by addressing further topics in the recommended reading, but for a public engagement talk, it is likely that my reference list isn’t going to be the key focus of my pub-based audience, however, if keen and interested listeners make it as far as Wikipedia to read more about phage, they will at least meet lysogeny.

This decision highlights a key challenge in public science talks: completeness versus clarity. Sometimes, leaving something out is the best way to keep your audience engaged and curious.

Conclusion

Storytelling is a powerful tool for capturing attention, driving engagement, and sparking curiosity. While it might seem like storytelling could oversimplify the content, using a spiral approach helped to avoid this. By revisiting topics in more detail, the audience gain a deeper understanding over time.

In the end, using storytelling in my talk on phage biology worked really well. It made the scientific content more accessible and engaging for the audience. I was massively relieved to receive positive feedback from members of the audience, hearing comments like “Phage are amazing!” and “I want to learn more about DNA!” reminded me why public engagement matters. If you're planning a similar talk, remember: pitch carefully, tell a compelling story, and build understanding step by step.

I would like to express a huge thank you to the Lincoln Pint of Science team for the opportunity to share my work in such a fun environment. I’d also like to thank the amazing artist Vix who created the stunning artwork as a Creative Reaction to my work.

References

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The Process of Education. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

McDrury, J., Alterio, M., (2003). Learning through storytelling higher education: Using reflection & experience to improve learning. London: Routledge

Links

The Pessimist Wine Bar & Restaurant (@thepessimistlincoln) • Instagram photos and videos